Section Branding

Header Content

The secret world behind school fundraisers and turning kids into salespeople

Primary Content

Maria Lares is arguably the heart and soul of Villacorta Elementary School in La Puente, California. She's been teaching at the school for more than 30 years and has been on the Parent-Teacher Association there the entire time.

"The PTA actually means a lot to me," she says. "I'm an immigrant, and when I got here my parents – they worked 12 hours a day. So they never attended any school things. So as a teacher I said, 'Uh-uh, PTA's my baby!' And it has been for all these years."

The way Maria sees it, the main job of the school's PTA is to fund the activities that make school fun for kids — e.g., pizza parties for the honor roll students, bringing in a big reptile show for kids, or helping pay for the 6th graders to go to science camp for a week.

This year, Maria's number one priority is for the PTA to raise enough money to send every single kid at the school on at least one field trip.

It's been three years since the whole school went on one. The school didn't fundraise in time last year, and they didn't go on field trips the previous two years because of COVID-19. So this year, Maria is determined to make field trips happen. And she's looking forward to one field trip in particular for her first graders.

"I like to take my class to the beach. On a boat ride," she said. "They'll tell you, 'I've never been to the beach!' They have never been on boats before."

The beach is just 40 minutes away, but 90% of students at this school are economically disadvantaged and 20% are unhoused, so many of her students have never seen the ocean.

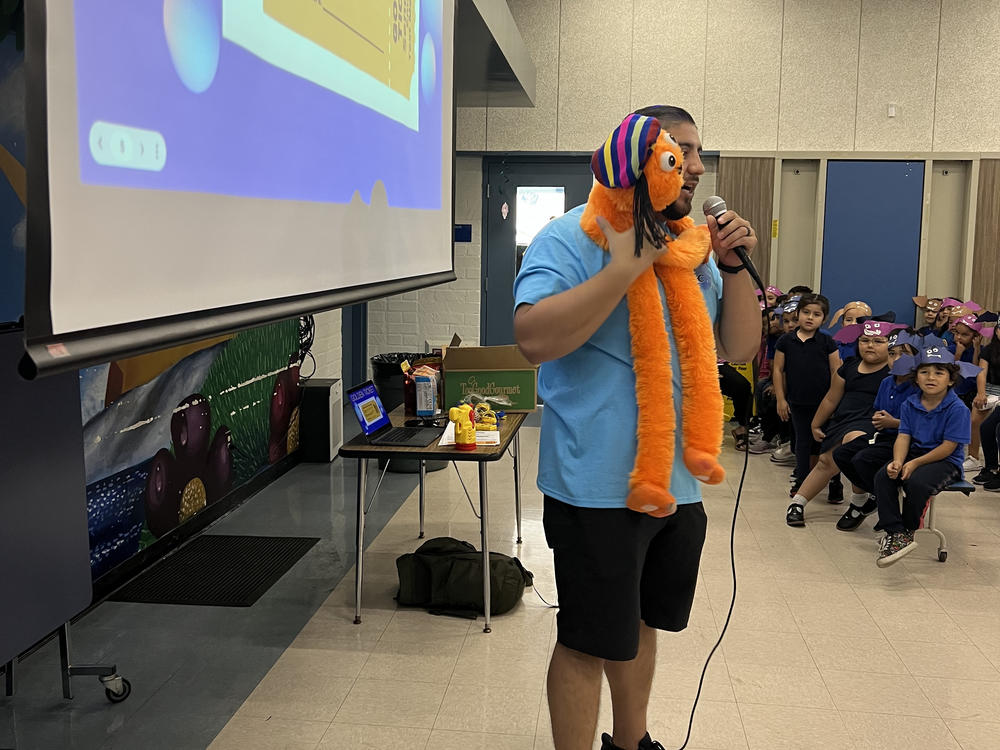

To pay for a trip to the beach and all the other field trips, the PTA at Villacorta Elementary raises money through their own fundraisers, like nacho sales and t-shirt sales. But those don't generate huge amounts of money, so once or twice a year, they'll go through a school fundraising company. Those companies put on these flashy assemblies where they show students all the prizes they could win if they sell enough chocolate, or popcorn, or wrapping paper.

Now offsetting the costs of field trips with fundraising happens at pretty much every school. Wealthy schools also fundraise to help cover the cost of their more expensive trips.

But why is this the system? Why do schools let companies come in to turn kids into little salespeople?

Public schools get their official budgets from local property taxes, as well as states and the federal funding. Technically, schools get more money per student today than they have historically gotten.

For Villacorta Elementary, the district gets around $4.5 million a year. It's about $16,000 per student at this school, which is a little more than the national average of $14,347, according to 2021 Census Data. But it's not like the principal gets all of that money to spend. The district actually spends almost all of it on things like salaries for teachers and benefits and the cost of running the building. What the principal gets to spend is closer to $1,200 per kid. And because it's public funds, there are a lot of rules about how he can spend this money.

"It's sort of a give and take," says the principal George Hererra. "If I put [the money] to field trips, then I shortchange somewhere."

But when the PTA raises money from fundraisers like selling cheesecake or chocolate, that is not part of the official school budget. It is not "public funds." So this money can go to anything. Which is very valuable to a school.

Marguerite Roza, a school funding expert at Georgetown Universitiy's McCourt School of Public Policy, said it would be possible to just change the rules about how school money can be spent. And, she said, if a school really wanted to prioritize field trips in their official budget, they could. No fundraising from the PTA necessary.

Because, of the $1,200 the principal gets per student, around $500 could be spent on field trips. That would be enough money to send everyone at the whole school on approximately 17 field trips a year. But that is not what this principal does.

George chooses to spend his budget on a teacher's aide for his students that are learning English and an attendance clerk to try to deal with the school's attendance problem. The clerk calls parents when a student is absent to ask why their child is missing school.

"For me, my decision is very academic-based. You know, what intervention do we need? Do we need to hire an intervention teacher? Do we need to provide after-school tutoring?"

And choosing to prioritize his budget this way might be tactical.

Marguerite Roza, the school funding expert, says it is a lot easier to ask parents and the community to pitch in for something like field trips than it is to go around asking parents to donate money to pay for the salary of an attendance clerk. The PTA could fundraise for that instead. But schools all over the U.S. choose to fundraise for the fun school perks instead because it works. People like to give money for this kind of cause.

But that means the fundraisers never stop.

Every year the PTA at Villacorta has a goal to raise $20,000. To get there, they held about 10 fundraisers: a popcorn fundraiser, a Mother's Day shop, a jogathon but with bubbles called a "bubble run." For one fundraiser, the teachers worked at McDonald's for a day. (The teachers made the fries, and the principal served cookies.)

When the school uses a fundraising company, the company takes a cut of everything students sell. In Villacorta's experience, the company usually gets 60% and the school gets 40%, which is not the best deal. But the companies help the school bring in more money per fundraiser.

After a year of fundraising, Maria's school was just shy of their $20,000 goal. The sixth graders were the first to go on a field trip.They went to the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California. But, all the other grades still have to go on their field trip; Maria's beach trip for the first graders still has to happen. So, the fundraising continues.

Their next fundraiser starts March 18th. They're selling peanut brittle, gummy bears and chocolate covered popcorn.

Today's show was hosted by Sarah Gonzalez and produced by Sam Yellowhorse Kesler. It was edited by Jess Jiang, fact checked by Sierra Juarez, and engineered by Valentina Rodríguez Sánchez. Alex Goldmark is Planet Money's executive producer.

Help support Planet Money and get bonus episodes by subscribing to Planet Money+ in Apple Podcasts or at plus.npr.org/planetmoney.

Always free at these links: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, the NPR app or anywhere you get podcasts.

Find more Planet Money: Facebook / Instagram / TikTok / Our weekly Newsletter.

Music: Universal Production Music - "No School No Rules," "Give 'Em That Old School," "Penny Farthing," and "Back to School"