Caption

This 10-foot great white shark vanished off Georgia in April and resurfaced five months later in the Gulf of St. Lawrence off Canada, OCEARCH reports.

Credit: OCEARCH Facebook screengrab

This 10-foot great white shark vanished off Georgia in April and resurfaced five months later in the Gulf of St. Lawrence off Canada, OCEARCH reports.

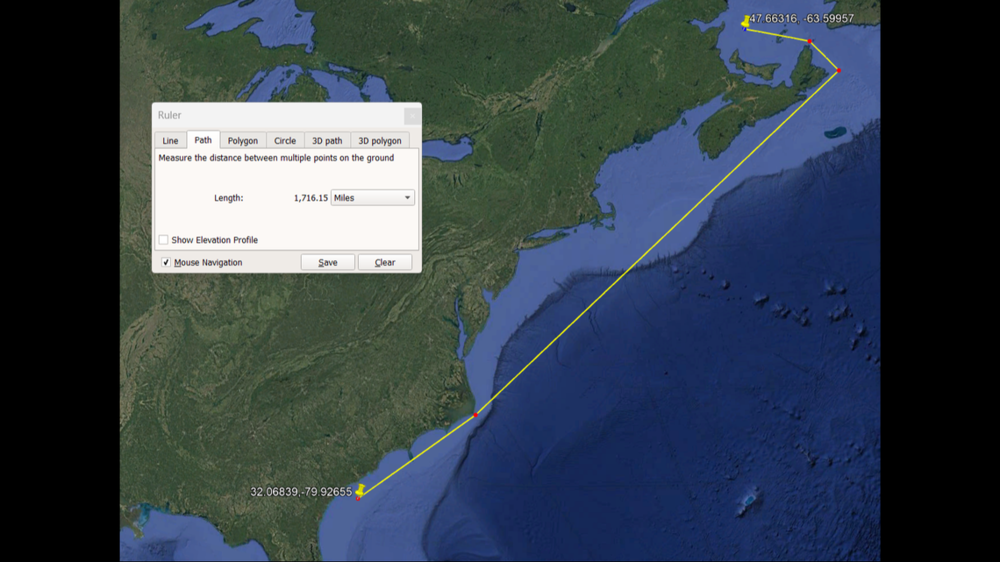

As strange as it sounds, a 10-foot, 3-inch great white shark sporting a satellite tracking tag managed to swim more than 1,700 miles without giving away her location, according to the nonprofit OCEARCH.

The 522-pound shark was off Savannah, Georgia, on April 21 when it went into stealth mode, data shows.

It resurfaced Sunday, Oct. 6, in Canada’s Gulf of Saint Lawrence. That’s about 1,372 in straight-line miles and 1,716 waterway miles, OCEARCH told McClatchy News.

Assuming the shark, named Penny, made a lot of pit stops, that comes out to about 340 miles a month.

The reason for the long trip north is pretty clear, scientists say. She’s hunting something.

“She’s up in the rich feeding grounds,” OCEARCH noted in an Instagram post. “Tremendous amount of bait there. Tremendous amount of blue fin tuna as well as plenty of gray seals.”

Penny was fitted with a satellite tracker tag in 2023 off North Carolina’s Outer Banks and data has revealed she, like other white sharks, is using the East Coast as a highway. She has traveled 6,873 miles in 532 days and has been as far west as the coastline off Tampa, Florida, OCEARCH says.

White sharks prefer the southeastern United States in the winter, and will linger for months in the Gulf of Mexico. In the summer, they head back north to cooler waters off New England and Canada.

Somewhere in between the Gulf Coast and Newfoundland are white shark mating and nursing grounds and OCEARCH is working to pinpoint that location. It’s believed to be in the waters off the Outer Banks.

This map provided by OCEARCH shows the trip the shark made without giving away her location.

To show up on satellite, the shark’s tag, stuck on the dorsal fin, needs to breach the surface multiple times at a location, and for more than a just few seconds.

Occasions where a tracker tag breaches the surface only momentarily are called Z-pings, which are too weak to provide a location. In Penny’s case, she emitted 20 Z-pings during the past five months, OCEARCH says. At the least, those Z-pings proved she was still alive and the tracker was still working.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Macon Telegraph.