Caption

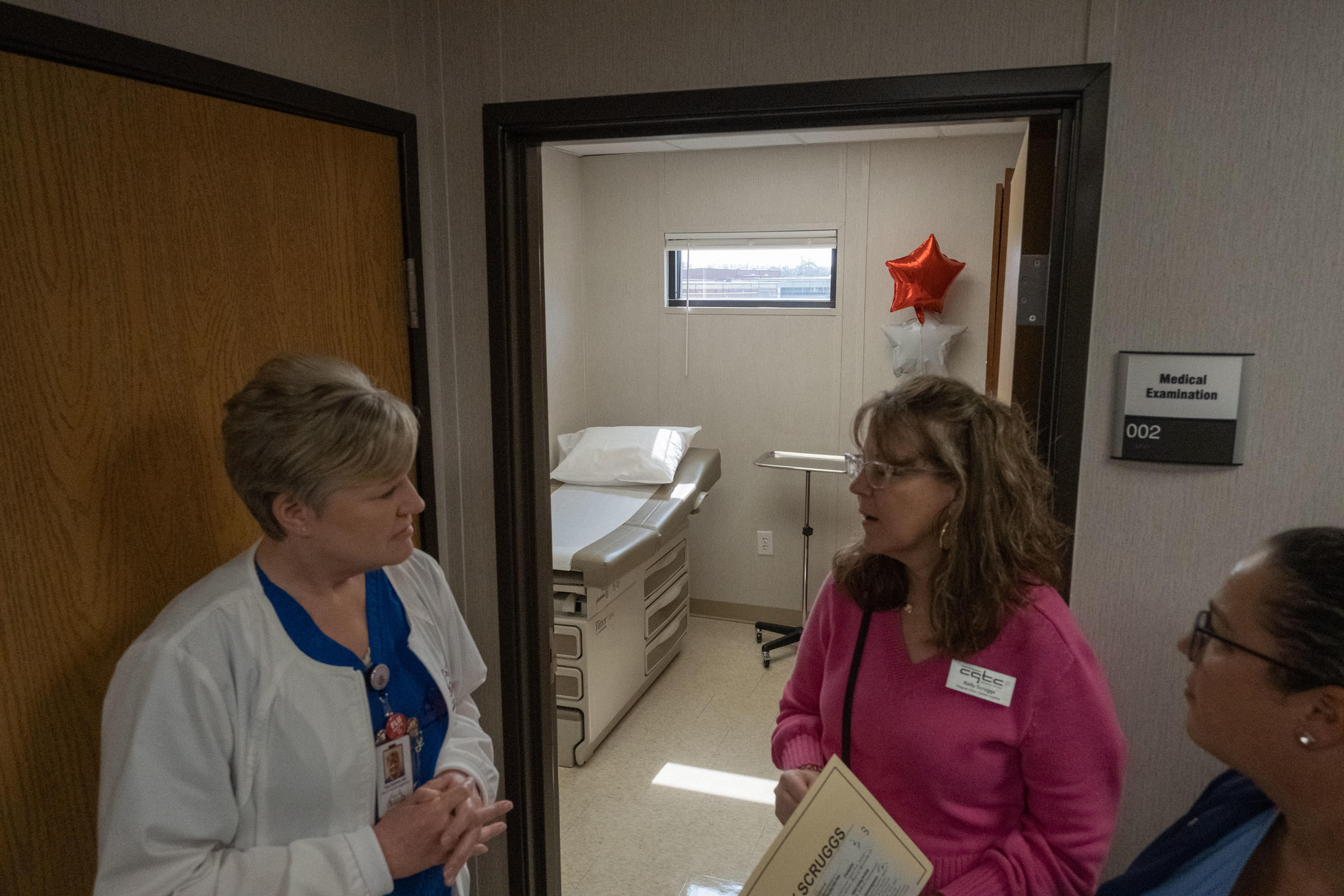

The grand opening of the Wellness Center at Jeffersonville Elementary School in Twiggs County was held in March 2024.

Credit: Sofi Gratas/GPB News

|Updated: April 18, 2024 11:08 AM

LISTEN: A state investment of $125 million dollars from federal COVID relief funds is helping grow school-based health through grants issued by the Georgia Department of Education. GPB's Sofi Gratas has more.

The grand opening of the Wellness Center at Jeffersonville Elementary School in Twiggs County was held in March 2024.

In March, at Jeffersonville Elementary School in Twiggs County, Ga., school staff, parents and students toured a brand-new clinic.

Inside, there’s a room with a TV for telehealth, and two empty suites being prepped for dentist chairs. There are rooms for primary care, too. It smells like fresh paint.

This clinic will be one of about 30 new or expanded school-based health centers to be up and running over the next few years. The expansion is part of $125 million investment from the state fueled by federal COVID relief funds.

Through grants issued by the Georgia Department of Education, school districts like Twiggs County were able to apply for up to $1 million to help build and support the startup of these health centers.

Mack Bullard is the superintendent of the Twiggs County School District.

“And it's not just for the kids, but if they have a little brother at home or a grandparent at home, they can come and be seen too,” Bullard said.

What he describes is a big difference from the school nurse's office you may remember, and a big deal in Twiggs County where kids and adults are largely uninsured. Many don’t see a doctor or dentist regularly.

Bullard said he realized it was the school district’s job to help fix this.

“All of those were barriers,” Bullard said of the hurdles of under-insurance and distance to health care. “And we knew as a result, our students weren't able to truly maximize their learning because all those barriers existed.”

By partnering with a federally qualified health center, this clinic on the elementary school’s campus is open to anyone, regardless of whether or not they can pay the bill for care.

“It's really sort of taken the work that we started about 15 years ago sort of to scale,” Veda Johnson said of the state’s investment.

Johnson is a professor of pediatrics at Emory University, which, up until two years ago, was largely responsible for funding the growth of school-based health around the state through private grants. Georgia has over 100 of these clinics as a result of that work.

Standing in front of the new clinic in Twiggs County, Johnson called the multi-million dollar investment from the state an “embarrassment of riches.” It's the first time the state has made such an investment in the model.

Though steps away from the school, the clinic at Ingram Pye Elementary in Macon sees more adult patients then children.

Research shows school-based health works to keep schools healthier, but also to improve grades, enrollment and attendance.

That reflects the experience at Ingram Pye Elementary School, 30 miles away in Bibb County.

There, Katherine McLeod says she saw a shift when the district first opened a clinic just around the corner from the school’s front doors. McLeod runs First Choice Primary Care in Macon, the practice that partners with Ingram Pye.

“When we first got started and were seeing a fair number of children, the school could see an immediate improvement in attendance,” McLeod said.

The change was brief, but McLeod believes it was because parents could send their kids to the clinic during school, rather than keep them and their siblings home or pull them out of class when they felt sick.

Those parents could also now come in themselves. McLeod says that explains another shift — on most mornings, the waiting room at the clinic is full of grownups.

“Fairly quickly, people in the neighborhood realize we're here,” McLeod said — a neighborhood where cost and transportation were once the biggest barriers to health care. “Currently we see more adults than children.”

Even though it’s not full of kids, the clinic at Ingram Pye stays busy — enough so that the Bibb County School District has plans to build another clinic at a different school using some of that multi-million dollar investment from the state.

McLeod said they’re not sure where it will be yet, but that this time, they want it inside of a school, to hopefully attract more kids.

Carolina Lideno holds her baby after a brief dental exam at the pop-up clinic hosted by the Houston County School District in February 2024. Each blue clipboard holds information about a different screening available that day.

So far, clinic funds have only gone to school districts which are either rural or on the state department of education’s list of academically underperforming districts.

A spokesperson for the Georgia Department of Education said it was always the intention that these dollars appropriated by the governor in 2022 go to support these types of school districts.

That puts people like Zabrina Cannady in a tight spot.

“We don't have schools that are on those lists,” Cannady said.

Cannady is with the Houston County School District. It’s not rural, and while Cannady says she’s glad Houston schools don’t meet the academic bar for health clinic funds, they still see health-related barriers to school success.

So, Cannady helped organize a pop-up clinic on a weekend in February hosted at the district’s Lindsey Student Support Center.

“With us not qualifying, we're still trying to bring services,” Cannady said.

By the end, over 100 kids and adults came through for free checkups, mental health evaluations and dental and vision exams.

One visitor was Carolina Lideno, who brought her mother and baby to the event while her son was at school.

“We took advantage of everything,” Lideno said in Spanish, adding that it's because it’s not always possible to go get a checkup.

“And if they refer us to a doctor, we’ll look for one,” she said.

Down the hall, Josh Lounsberry said he took advantage of services while getting his son enrolled for the next semester.

“I've never, never, utilized any kind of public assistance like this before, so it's a little bit different for me,” Lounsberry said. “But it's great that it's available.”

Whether or not it stays available will be largely reliant on community partners and volunteers, as long as Houston County stays ineligible for funds to build a permanent clinic.