Section Branding

Header Content

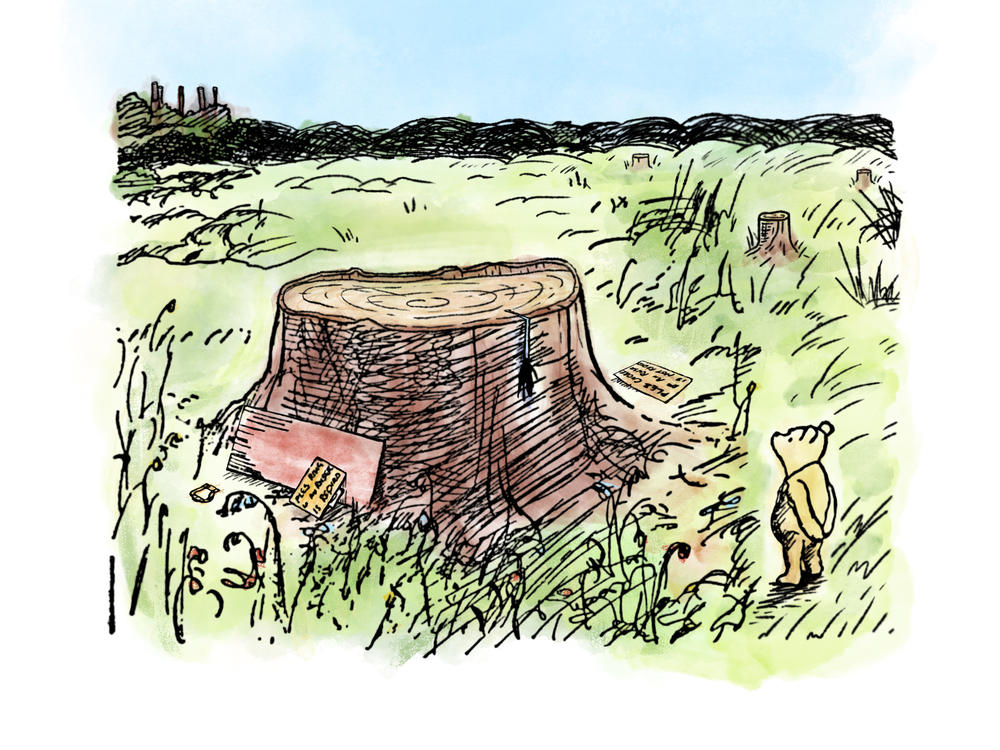

Oh Bother! Winnie, poo and deforestation

Primary Content

Winnie-the-Pooh: The Deforested Edition is a reimagining of the A.A. Milne classic created by the toilet paper company Who Gives A Crap.

There is just one, stark difference: There are no trees.

The Hundred Acre Wood? Gone.

Piglet's "house in the middle of a beech-tree" is no longer "grand."

Six Pine Trees is six pine stumps.

Yes, this is imaginative PR (a free eBook is available on the Who Gives A Crap website; a hardcover was available for purchase but is now sold out). But the company's co-founder, Danny Alexander, said the goal is to raise awareness about deforestation. Who Gives A Crap prides itself on "creating toilet paper from 100% recycled paper or bamboo," he said.

Without trees, Winnie-the-Pooh can't fall out of branches in his pursuit of honey. Christopher Robin can't climb the big oak. Owl's home at The Chestnuts is barely there.

These sad predicaments are "kind of the point," said Alexander.

Deforestation destroys ecosystems. "Animals and plants lose their habitats, naked land becomes unstable," said NPR's Climate Desk reporter Rebecca Hersher. "But deforestation also contributes to climate change because forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere."

As the United Nations put it, "Forests are essential to life on earth."

Alexander said Who Gives A Crap has tried to spread the word that "over a million trees are cut down every single day just to make traditional toilet paper," according to a study the company commissioned.

"But it's a hard message to get across and it's really hard to imagine," he said.

Who better to enlist in the effort than an adorable, world-renowned bear?

"It's just an extremely powerful re-use of the original Winnie-the-Pooh book to convey that even a bear 'of very little brain' could appreciate the impacts of deforestation," said Jennifer Jenkins, director of Duke University's Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

Reimagining — or ruining — iconic stories?

Once artistic works are in the public domain, they are no longer protected by copyright law. They belong to the public. Other creators are free to reimagine them as they see fit.

Frozen drew from the fairy tale The Snow Queen. Demon Copperhead is an adaptation of David Copperfield. "The Great Gatsby Glut," read a New York Times headline for a piece on all of that novel's adaptations. Pride and Prejudice, Shakespeare, Greek myths...creativity begets creativity, not all of it worthy of the original.

As for Winnie-the-Pooh, the story's been made into a slasher film that "nobody asked for," according to Fatherly and was parodied by Ryan Reynolds in an ad for Mint Mobile.

This Pooh's shirt is purple

The original 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh illustrations by E.H. Shepard were in black and white. Pooh first appeared in a red shirt in the early 1930s. That and other colorized versions are not yet in the public domain.

Writer Tim X. Rice had some fun with Winnie-the-Pooh's public domain entrance, instructing those who might rework him: "Red shirt on the bear, artists beware. If nude he be, your Pooh is free."

Misleading messages

Tensie Whelan, founding director of the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business is weary of stories where "forest products companies are the villain." While some of them "absolutely are destructive," she said, "most forest products companies today are doing it much more sustainably."

She says Who Gives A Crap is, "taking something that is relatively complex" and "then sort of manipulating kids into an emotional response using this, you know, wonderful story in order to sell their product."

"100% recycled paper still comes from trees," she noted. Recycled paper operations also rely on burning fossil fuels, adding to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change.

Whelan is also concerned that the tone is too dark for kids. "We want kids to see the upside and the opportunities and not scare them too much."

What would Pooh think?

Alexander, the company co-founder, conceded that seeing images of Winnie-the-Pooh, Piglet, Christopher Robin and the rest of the characters living in a world without trees is "uncomfortable and jarring."

Alexander wants the Deforested Edition to, "spark a conversation between parents and children...about the impact our daily habits have on the environment, and how we can all be part of the solution."

At first, he said, he and his colleagues at Who Gives A Crap struggled with the idea of tampering with such a beloved character but "ultimately the message you're trying to get across here is one that's really powerful and is challenging, and I think it kind of fits the message." He said they decided not to contact the A.A. Milne estate about their new version.

"The way we thought about it is really, what would Winnie-the-Pooh think? And from our perspective...we think that he would be proud of it and we think he'd agree with it."

A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard's literary agency declined NPR's request for comment.

Next year, Mickey Mouse comes into the public domain. We could imagine all kinds of dark scenarios in which he might appear.

But we won't. Disney will probably put up a fight to keep its famous characters on brand.

This story was edited by Meghan Sullivan and Jennifer Vanasco with help from NPR's Climate Desk.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.