Section Branding

Header Content

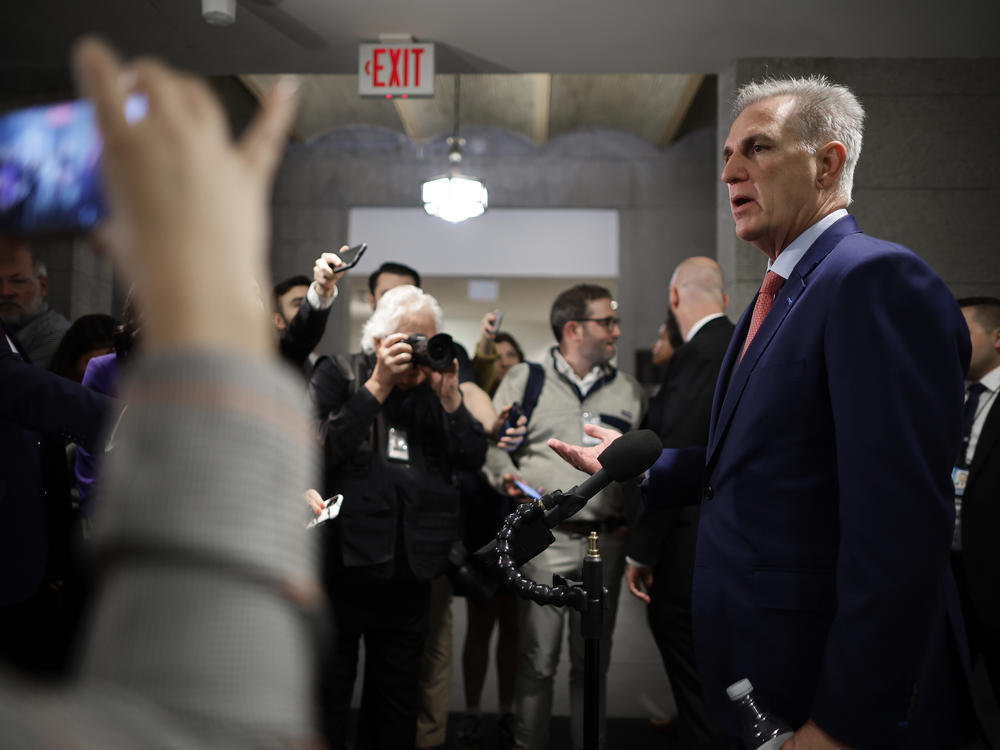

McCarthy revives immigration battles in bid to shift shutdown blame from GOP feuds

Primary Content

Days ahead of a possible government shutdown, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy is trying to shift the conversation away from internal party divisions — toward the Biden administration's handling of the southern border.

In recent days McCarthy, R-Calif., has repeatedly sidestepped reporters' questions about the House's plans to keep the lights on at federal agencies and whether he would work with Democrats on any spending plan. Instead, he is insisting that a short-term stopgap spending measure to keep the government funded include Republican-passed border policies.

But that stopgap measure is a nonstarter in the Senate, and right now it's not even clear House Republicans can even get it across the finish line later this week.

Citing statistics saying 11,000 migrants are entering the U.S. illegally each day, McCarthy has argued that the president and Senate Democrats have ignored the situation at the border. He points out that Democratic officials in New York and other states have expressed concern about the recent influx of migrants, and that President Biden is ignoring their calls for help.

McCarthy is calling on the president to take action, but it's Congress' role to approve annual funding bills, and the speaker has struggled to get enough votes to bring up their party's own proposals. The House did agree to move forward on four appropriations bills this week, but none of those are expected to advance in the Senate, and none would avoid a shutdown.

Arkansas Rep. Steve Womack said he and other McCarthy allies want to keep the government open, but emphasized that in any short-term spending bill, "there's gotta be something in it for us as well, and what we really want and what we have been begging for is the ability to get better control of our southern border."

Senate and House GOP split

The top Senate Republican, Sen. Mitch McConnell, argued that a shutdown wouldn't achieve what House Republicans say are the problems at the border, and defended a bipartisan bill Senate leaders unveiled Tuesday that would keep federal agencies funded through November 17.

McConnell said Wednesday "a vote against a standard, short-term funding measure is a vote against paying over $1 billion in salary for CBP and ICE agents working to track down lethal fentanyl and tame our open borders."

He said he didn't want to offer any advice to House Republicans, but noted that border agents would be working without pay in a shutdown "so I don't think, even those of us who are deeply concerned about the border, I don't think that's more likely to happen in a shutdown than with the government open."

The No. 3 Senate GOP leader, Wyoming Sen. John Barrasso, said Senate Republicans would work on amendments to address the increase in migration and issues related to illegal drugs. He told reporters the American people "deserve a government that is open and a border that is closed."

West Virginia Sen. Shelley Moore Capito said she backs adding some immigration provisions to a stopgap bill, but added, "at this point right now 77 percent of the American people do not think we should shut the government down. And I'm in the 77 percent."

McCarthy said there wasn't support for the Senate's plan among House Republicans. Many oppose the $6 billion in aid to Ukraine.

Florida GOP Rep. Byron Donalds told reporters that the Senate bill is a "nonstarter" and added, "the Senate needs to get real. You've all seen the images at the southern border. It has to stop — immediately. And this government should not continue to be funded if we don't secure our border."

McCarthy's narrow margin

But as McCarthy ignores a bipartisan plan that advanced 77-19 in the Senate, he has little room for error with his own proposal. The speaker can only afford to lose four votes from his own party, and it appears already he is short. Several hardline conservatives in the House continue to oppose any short-term funding bill.

McCarthy has suggested those holdouts are siding with Biden by refusing to back a bill with increased border funding. Florida GOP Rep. Cory Mills, one of the hardliners, told reporters that is "absolutely false."

"If they want to play politics with messaging, then by all means, let them go ahead and do that. My vote remains the same," Mills said. "We do care about securing our borders. We've made that a top priority."

Arizona Rep. Andy Biggs said the focus should remain on approving all 12 of its annual spending bills, not stopgaps.

"I choose long-term sustainability over short-term rhetoric," Biggs said in a post on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Rep. Eli Crane, R-Ariz., and Rep. Matt Rosendale, R-Mont., have also said they oppose any continuing resolution, or "CR," to keep agencies funded as the House and Senate negotiate on spending bills.

Tennessee GOP Rep. Andy Ogles pointed to the deal McCarthy cut in January to gain the votes to be elected speaker, which included a pledge for House votes individually on all annual spending bills.

"Now our back's up against the wall, and we're going to force 12 appropriations bills," he said. "And if that means we close and that we shut down, that's what we're going to do."

Many conservatives seem unmoved about the impact that any shutdown would have on federal workers or those who rely on federal assistance. McCarthy on Tuesday redirected questions about workers concerned about furloughs again to border concerns.

Rep. Ralph Norman, R-S.C., shrugged off a report that millions of women could lose aid from the Women, Infant and Children nutrition program if the government shuts down:

"OK yeah, you hear all that. Granny's going over the cliff. What about the country going to the cliff?" he said. "That's ludicrous. I've heard that song and dance all over again. They're going to use that, any cut."

The government shutdown in 2018 was also triggered because of a fight over the border. At the time, former President Trump was insisting that any spending bill include money to build a wall along the southwest border. He refused to support a bill that didn't meet that demand. After a record 33 days, the president gave in and agreed to a bill to reopen the government without any new funding for the wall.

McCarthy could avoid a shutdown if he chose to work across the aisle with Democrats to approve a stopgap bill, and there continue to be some discussions with group of moderate House Republicans and Democrats about a proposal to avoid a shutdown, or get out of one.

Rep. Mike Lawler, R-N.Y., represents a suburban district that Biden won in 2020, and has been part of those bipartisan talks. For now he's backing the speaker's strategy and says the biggest issue facing the country right now is immigration and the Biden strategy has failed. But he warned if his fellow House Republicans don't stand together they will get blamed for a shutdown, "all I can do is encourage my colleagues to be smart, to be strategic and to understand that you can't win with nothing."

McCarthy could face threat for his gavel

Hanging over the speaker as the deadline when millions of federal workers will be furloughed and stop getting paid is a threat that if he cuts a deal with Democrats one of his critics will bring up a resolution to oust him from his job.

Florida GOP Rep. Matt Gaetz reiterated that threat again on the House floor on Tuesday, but McCarthy shrugged it off. But his move to shift the blame to the president about a funding fight he's unable to resolve among his own members demonstrates his focus for now is on keeping his position.

Womack, an ally of McCarthy's, admitted the chance of a leadership challenge from the critics on the far right is real, saying, "negotiating with Democrats and negotiating with even some Senate Republicans can be problematic for the speaker."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.