Section Branding

Header Content

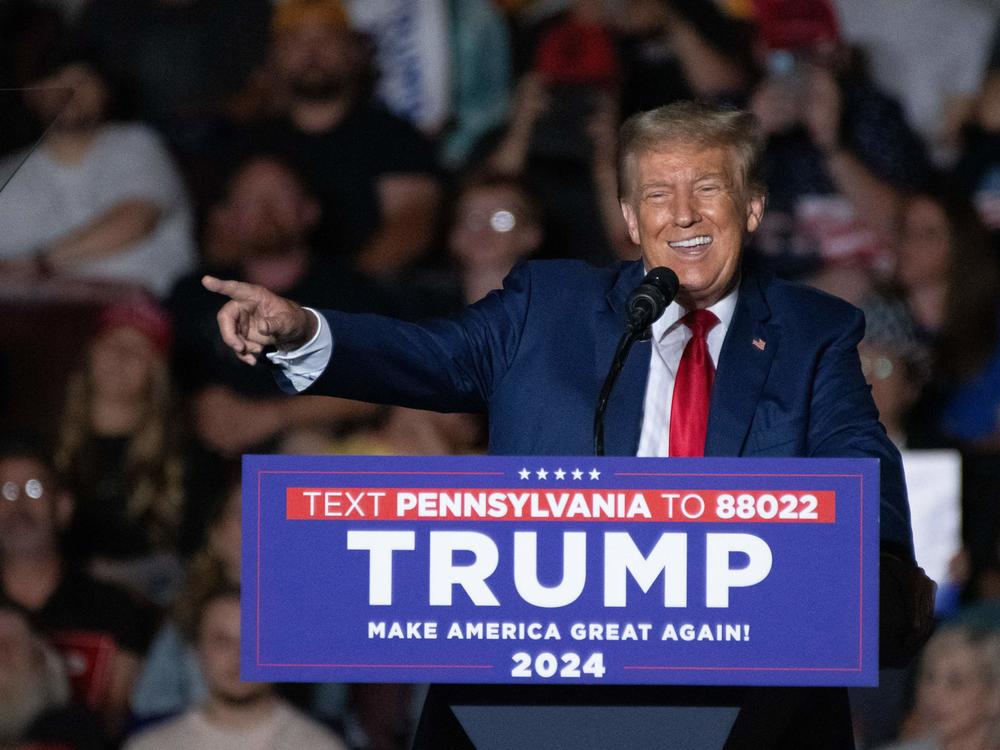

Why the Trump indictments have not moved the needle with Republicans

Primary Content

With each passing indictment of former President Donald Trump — up to four now in less than five months — its seems he's only solidified his grip on the Republican Party.

Trump is the far-and-away front-runner for the GOP presidential nomination again and has raised gobs of money off of the legal developments. About half of Republican voters seem nearly locked in for Trump and believe his baseless narrative of deep-state conspiracies against him.

At this point, with a fourth indictment that came out of Georgia on Monday night, stemming from his and allies' attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election in the state, plus ones in New York and two at the federal level, the GOP base appears to believe the conspiracy is pretty far and wide.

Few of Trump's Republican primary opponents are criticizing him on the charges, and the GOP officials who do are turned into political pariahs.

But what explains this? And is this "nothing matters" narrative actually something of a mirage — at least with the broader electorate?

Let's dig in.

A repelling effect with independents

First, let's start out with the fact that the indictments have mattered politically.

With most Americans, Trump remains highly unpopular.

His favorability rating, on average, is only about 40%. With independents, he's in the 30s in the latest polling.

And Trump has had a repelling effect with independent voters, who lean toward one party or the other and often decide the outcome of elections.

More than half of independents — 52% — said they think Trump has done something illegal, the latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll found. That's up 11 points since March, just before the first indictment in New York was released related to Trump's hush-money payments to women he was alleged to have had affairs with.

Remember, that change comes after Trump's brand hurt Republicans in the 2022 midterm elections. Democrats won independents in the midterm elections by 2 points, according to exit polls, which led to Republicans winning a smaller-than-expected majority in the House, and Democrats picking up a seat in the Senate.

That result defied the history of how the party out of power usually performs in midterm elections. For example, when Trump was president, Democrats won independents by 12 points in 2018. Republicans, on the other hand, won them by double digits in the midterms during Obama's presidency.

In both 2016 and 2020, Trump got less than 47% of the vote — 45.9% in 2016 and 46.8% in 2020. That was before Jan. 6 and these multiple indictments.

Trump has done very little to expand beyond his base in the years since, and his toxicity with independents makes it hard to see his path to winning back the White House in 2024 — without a little help from a potential third-party bid. (More on that below.)

Now, where it hasn't moved the needle is with Republicans

Republicans are living in a different universe than Democrats or independents when it comes to Trump.

Trump has insulated himself with many Republicans with his cries of witch hunts, political targeting and a healthy dose of whataboutism complaints of double standards.

After the 2020 election results were in, and his campaign manager and other high-ranking officials in his administration were telling him he lost, Trump routinely took to Twitter (now X) and conservative media to lie about the election.

He would talk about conspiracies with no founding, some of which are cited in the Georgia indictment, as if they were proof of things that either had already been disproven or would go on to be.

Trump is set to use that playbook again in a news conference he's set for Monday from his golf course in New Jersey. He's promising an "irrefutable" and "conclusive" report that will show he was right about a "rigged election."

Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, whom Trump has targeted because he wouldn't validate his attempts to overthrow the election and lies about widespread fraud, swatted Trump's claims aside.

"The 2020 election in Georgia was not stolen," Kemp wrote on X. He noted correctly that no one with actual evidence of fraud has proven anything, under oath, in court. "Our elections in Georgia are secure, accessible, and fair and will continue to be as long as I am governor."

But Kemp — and Republicans like him — have been in the minority in their Trump-dominated party. Because of the warm feelings base voters have for Trump, few in the GOP have been willing to stick their necks out for fear that, politically, they'll be chopped off.

The ones who do have suffered politically. Only two of the 10 House Republicans who voted for Trump's impeachment, for example, still have those jobs.

And the primary opponents who've spoken out most forcefully don't have much support, like former Vice President Mike Pence, former Govs. Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas and Chris Christie of New Jersey, or former Rep. Will Hurd of Texas.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and others have emphasized a "double standard" with relation to the Justice Department, which has only served to further erode trust and confidence in the key law enforcement institution.

The GOP contenders are likely going to have to address the indictments at their first debate in a week — whether Trump is there or not. Trump says he won't sign a pledge to support whomever the Republican nominee is, as is required by the party's rules to participate.

That shows that for Trump, this really is a party of one.

Republicans, particularly in the House, and conservative media are helping him with that image, creating a false equivalence between the charges against Trump, a former president who is accused of undermining democracy, and Biden's son Hunter, who faces misdemeanor charges related to his taxes (a special counsel investigation is underway).

Republicans' attention to the Hunter Biden case seems to be an attempt to muddy the waters and carry a bucket of it to help shield Trump from his own legal and ethical woes.

Willing to believe anything?

The lengths to which many Republican voters are willing to go to believe Trump seems limitless.

Take what's at the core of Trump's argument — whether President Biden legitimately won the 2020 presidential election, which he did. Recounts, audits and more than 60 court cases have proven that to be the case.

And yet, look at the most recent polling on this. In July, a CNN poll found that by a 61%-38% margin, people overall believed Biden legitimately won, but only 29% of Republicans thought so. Almost 7 in 10 (69%) Republicans said he did not.

Of Republicans who said they believed Biden lost, 56% said they base that on "solid evidence," of which there is none, versus 44% who said it was their "suspicion" only.

The NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll has asked some similar questions after the 2020 election. For example, in December 2020, 61% said they trusted the results of the election. Big numbers of Democrats and independents said they trusted the results, but 72% of Republicans did not.

In October 2021, 62% overall said Trump continues to make these claims that the 2020 election was rigged mostly because he didn't like the outcome.

But, again, when it came to Republicans, quite a different story – 75% said it was mostly because he is right that there were real cases of fraud that changed the results.

The latest NPR poll found that Republicans and Republican-leaning independents had declined by 9 points in saying that Trump had done nothing wrong, from 50% to 41% from June to July.

Trump also dropped 6 points with the same group when asked if they were likely to support Trump or another candidate in the 2024 primary.

But a majority continued to say they preferred Trump to be the GOP standard-bearer in 2024.

That depth of (false) belief is going to be nearly impossible to overcome with ... facts, given how much Trump and his GOP have undercut expertise and the media.

Trump would likely need a little help from third-party candidates

Trump's lack of support with the middle makes it hard to see a path for winning another term.

But it's possible.

How?

Realize this: Trump got roughly a percentage point more of the share of the electorate in 2020 than 2016, but he lost.

Why? Look squarely at the third-party vote.

In 2016, 6% of voters cast their ballots for someone other than Trump or Democrat Hillary Clinton. In 2020, the third-party vote dropped to less than 2%.

That's a 4 percentage point difference. Biden's winning percentage? Just over 4 points.

And that's in the popular vote, which Biden won by 7 million votes and Clinton won by 3 million. The Electoral College was much closer. Only 44,000 votes in Georgia, Arizona and Wisconsin separated Trump and Biden from an Electoral College tie.

That would have likely meant Trump's reelection, given the House, which was controlled by Republicans, would have decided the presidential election, per the 12th Amendment. (It's happened before, but not since 1825.)

That's how close U.S. presidential elections are in this hyperpartisan era. So giving voters third-party options could tip the balance in the closest states, especially since both Trump and Biden are unpopular right now.

That's why Democrats are so worried about efforts like that of the group No Labels, which, this week, won ballot access in 10 states, including the swing states of Arizona, Florida, Nevada and North Carolina. That quartet of states was decided by a combined 7 points — less than a point in Arizona, 1.3 in North Carolina, just over 2 in Nevada and 3 in Florida.

Most polling has shown that a serious third-party candidate would pull mostly from Biden. One recent survey showed that might not necessarily be the case, but Democratic strategists are sounding the alarm nonetheless.

No Labels argues its goal is not to hurt Biden, but to give people "more choices at the ballot box."

But with the margins in the presidential election decided on a razor's edge and the country this divided, anything is possible.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.