Section Branding

Header Content

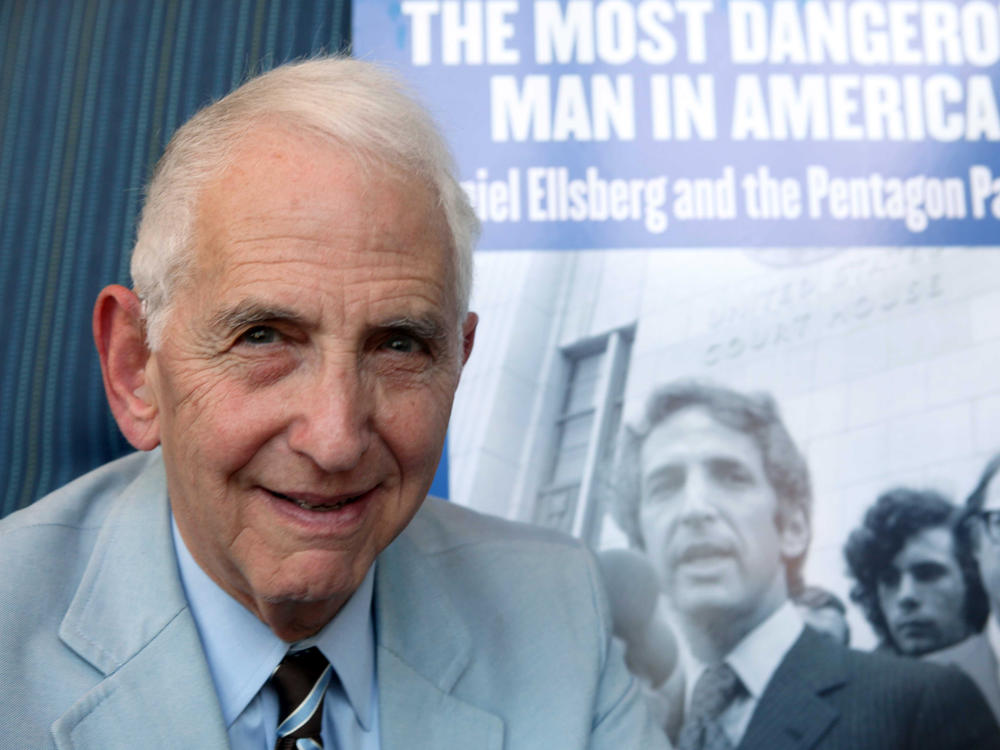

History-making whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg has died at 92

Primary Content

Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers that detailed U.S. actions during the Vietnam war, died Friday at this home in Kensington, Calif. He was 92. The cause, his family said in a statement, was pancreatic cancer.

In March, Ellsberg posted on his Facebook page that doctors diagnosed him with inoperable pancreatic cancer on Feb. 17 following a CT scan and MRI.

In the statement, Ellsberg family said that in the months since the diagnosis, "he continued to speak out urgently to the media about nuclear dangers, especially the danger of nuclear war posed by the Ukraine war and Taiwan."

"Daniel was a seeker of truth and a patriotic truth-teller, an antiwar activist, a beloved husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, a dear friend to many, and an inspiration to countless more. He will be dearly missed by all of us," according to the statement

Ellsberg never ran for office and only occasionally appeared on TV. But he altered the course of U.S. history in a way few private citizens ever have.

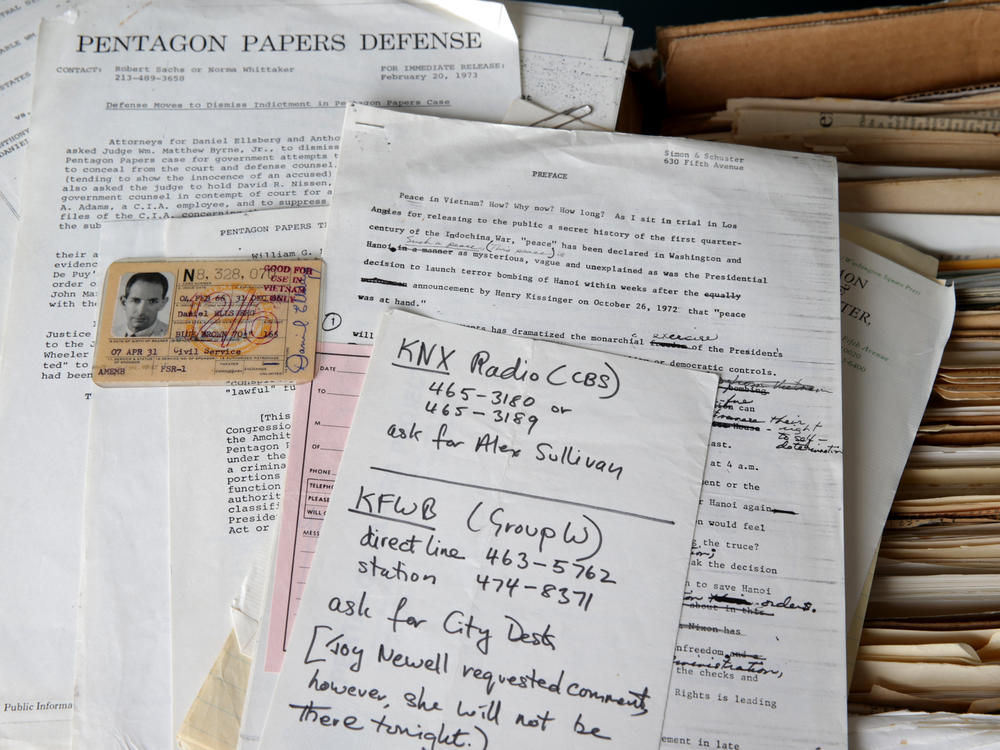

As a military analyst working on a Pentagon project in 1971, Ellsberg chose to release to the public an extensive, documentary record of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Known as the "Pentagon Papers," Ellsberg's mammoth disclosure would help to end the longest U.S. war of the 20th century. It would also prompt a landmark Supreme Court decision on freedom of the press. And it would provoke a response from President Richard Nixon that led directly to the scandals that ended his presidency.

By the time he got to the Pentagon, Ellsberg, then 40, was a Marine Corps veteran with a Harvard doctorate who had worked for the Defense and State departments and the Rand Corporation. A "hawk" before going to Vietnam in 1965, Ellsberg had since turned against the war and the official justifications given for it.

Since 1969 he had been one of dozens of analysts studying and writing about the decisions behind the escalating U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. The study covered the years from 1945 to 1968, and had first been commissioned by Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara toward the end of that period.

Ellsberg and a Rand colleague, Anthony Russo, had access to a copy of the 7,000-pages of classified documents and historical narrative kept at Rand. The pair photocopied them at night, one page at a time over a period of months.

Ellsberg showed the material to a few senators who had been critics of the war. He said he hoped they would hold hearings, or enter the report in the Congressional Record. But they were not willing to do so, and one encouraged him to go to the New York Times.

Ellsberg did just that, contacting a legendary reporter at the New York Times whom he had known in Vietnam, Neal Sheehan. Supported by the top editors at the Times, Sheehan led a team of writers and editors in distilling the immense document for newspaper use. On June 13, 1971, the first story ran atop the front page.

Sheehan wrote that the United States had gone to war not to save the Vietnamese from Communism but to maintain "the power, influence and prestige of the United States ... irrespective of conditions in Vietnam."

Revealing a quarter century of war and denial

The report that came to be known as the Pentagon papers said the U.S. had first been involved in Vietnam during World War II, when Americans helped Vietnamese resist Japanese occupation. After the war, the U.S. supported France's attempt to reclaim its colonies in Southeast Asia, largely to keep France in the alliance against the Soviet Union.

As the French forces faltered in Vietnam, the U.S. shouldered more and more of the cost of the war. And when the French gave up and left in 1954, the U.S. remained to protect Western investments and bolster an anti-communist government in Saigon (South Vietnam) while a Communist regime in Hanoi held sway in the country's northern half.

But almost none of this was known to the American public at the time, and when John F. Kennedy became president in 1961 he extended the commitments made by previous presidents. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, greatly expanded these commitments, escalating the war with hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops and relentless bombing campaigns in the mid-1960s.

Richard Nixon came to office in 1969 promising to end the war, but even as he reduced the U.S. troop presence he also widened the war into Cambodia and stepped up the bombing.

The most shocking revelation in Ellsberg's report was the willingness of one president and one administration after another to continue the commitment — and the upbeat assessments of the situation — even as they each came to believe the mission would ultimately fail, that no amount of conventional military force would subdue the Vietnamese resistance.

Ellsberg later summed it up by saying: "We always knew we could never win." Yet the war went on and more lives were lost because American leaders were unwilling to acknowledge the futility of the war or to accept the humiliation of defeat.

Although he himself had been part of the war machinery for years, and remained silent even after turning against the war, Ellsberg later reported having a dramatic conversion at a conference for draft resisters at Haverford College in August 1969.

In an interview 50 years later on NPR's Fresh Air, Ellsberg said: "Without young men going to prison for nonviolent protests against the draft, men that I met on their way to prison, [there would have been] no Pentagon Papers. It wouldn't have occurred to me simply to do something that would put myself in prison for the rest of my life, as I assumed that would do."

The threat of prison was quite real

The reaction to the papers' publication was immediate. President Richard Nixon's Justice Department got a federal judge to order the Times to cease publishing the stories. But Ellsberg was able to share another copy of the report with The Washington Post, which took up where its rival paper had left off. Other papers also stepped up. Besides the Times and the Post, at least 15 other newspapers stepped up to publish the Pentagon material in the critical days following the original release.

In that month, while the FBI searched frantically for the leaker, Ellsberg managed to elude his pursuers for11 days before turning himself in. The government charged him for violating the Espionage Act of 1917, a law passed during World War I and often abused to suppress dissent in that era. The sum total of the charges against him threatened a total jail term of 115 years, prompting reporters to ask if he had second thoughts about what he had done.

"How can I measure the jeopardy I'm in," Ellsberg asked, "... to the penalty that has already been paid by 50,000 American families and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese families?"

After his arrest, Ellsberg entered a period of legal limbo while awaiting trial, a period that would last nearly two years.

Meanwhile, the orders against the newspapers went to the Supreme Court on an expedited basis that June. The justices voted 6-3 to say "prior restraint" of publication required the government to meet a high test of necessity and irreparable harm — a test the court said had not been meant. The Times resumed publishing on July 1.

Why did Nixon pursue Ellsberg so vigorously?

The events and actions chronicled in the Pentagon Papers preceded Nixon's time in the Oval Office and could be blamed on his predecessors (most of them Democrats). But Nixon was angered and dismayed at their publication, convinced it would undercut support for the war and undermine respect for the government.

"The principle of confidentiality either exists or it does not exist," he said at a press conference. Tapes made in the Oval Office at the time recorded Nixon's profanity-laced denunciations of Ellsberg: "Let's get the son of a bitch into jail."

Nixon's national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, who had known Ellsberg as a military analyst years earlier, now labeled him "the most dangerous man in America." Both Nixon and Kissinger feared the revelations would torpedo their secret negotiations with Hanoi and Beijing. (As it happened, the Nixon administration was able to complete a withdrawal agreement for U.S. troops and a "breakthrough" diplomatic opening with China in the year after the papers were published.)

Ellsberg and others (including Nixon biographer John Farrell) have also contended that Nixon was worried by what Ellsberg would reveal about Nixon's backdoor negotiations with the Saigon government before he was president. While still a private citizen and a candidate for president in 1968, Nixon had signaled the South Vietnamese not to agree to peace terms proposed by President Johnson — promising them better terms if Nixon became president.

Whatever the source of his concerns, Nixon was not willing to wait for Ellsberg to come to trial. He directed various government agencies, including the CIA and the FBI, to find ways to discredit Ellsberg. In one conversation with his Attorney General John Mitchell (captured on the White House taping system in 1971) Nixon says: "Don't worry about his trial. Just get everything out. Try him in the press. Everything, John, that there is on the investigation, get it out, leak it out. We want to destroy him in the press. Is that clear?"

To that end, the White House created a covert squad known as "the plumbers" because they were hired to stop leaks of government documents that were embarrassing the administration — particular those leaked by Ellsberg. The operatives broke into Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office in Los Angeles but failed to find his file. When these and other illegal activities came to light, a federal judge overseeing Ellsberg's trial dismissed the charges. They were never reinstated.

While Ellsberg was still awaiting trial, the "plumbers" unit relocated from the White House to Nixon's reelection campaign organization and carried on their unlawful activities. These included two subsequent burglaries at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in Washington, D.C., located in the Watergate office complex not far from the White House.

On their second visit, the burglars were discovered and arrested in June 1972. Thus began the unraveling and revelation of numerous crimes, "dirty tricks" and official cover-ups known collectively as the Watergate scandal. Investigations and impeachment proceedings would push Nixon to resign in August 1974.

A quieter life with episodes of controversy

Ellsberg's name and prominence receded as time went on, and he devoted most of his time to teaching and writing. But he was often seen and heard at various protests involving war and peace, nuclear weapons and the actions the federal government took against whistleblowers.

His name became synonymous with resistance to government power, especially power exercised in secret. And he continued that career of resistance into his tenth decade of life, as an advocate for peace and a critic of government secrecy.

Ellsberg opposed the war in Iraq that began in 2003 and was a speaker at numerous rallies and events protesting that war and the suppression of its critics. In 2013 he said on Democracy Now that the U.S. had never taken responsibility for the Iraqi and Afghani lives lost in the U.S. invasions of those countries.

He also spoke out in defense of Wikileaks and its founder, Julian Assange, who has been fighting extradition to the U.S. for more than a dozen years. Ellsberg defended Wikileaks in 2010 for helping to build a better government. He also testified for Assange at an extradition hearing in 2020.

Assange has accused the U.S. of committing war crimes in Iraq and has published classified material such as diplomatic cables between the U.S. and other countries as well as documents on surveillance by the CIA and the National Security Agency. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Wikileaks released emails from the Democratic National Committee to Hillary Clinton's campaign manager.

Ellsberg also championed two of the whistleblowers Assange helped to make famous for releasing classified documents. The first was Chelsea Manning, a U.S. Army soldier and intelligence analyst who shared 750,000 records with Wikileaks in 2010. These included diplomatic cables, Army logs and diaries and videos of events such as a 2007 helicopter strike on a Baghdad street and another airstrike in Afghanistan in 2009, both of which appeared to have killed civilians.

Manning faced 22 charges, some under the Espionage Act and one of aiding the enemy, which could have carried a death sentence. She was sentenced to 35 years in confinement but had her sentence commuted by President Barack Obama in 2017 after she had served seven years.

Ellsberg also traveled to Moscow to visit and be photographed with Edward Snowden, a one-time computer intelligence consultant for the National Security Agency who had also worked for the CIA. In 2013, Snowden leaked information about surveillance programs run by the NSA and similar agencies of allied governments. Stories based on the documents involved appeared in The Washington Post, The Guardian and other publications.

Snowden was charged with stealing government property and, like Manning and Ellsberg, for violating the Espionage Act. He left the country and received temporary asylum in Russia at the time. In September 2022, Snowden was granted Russian citizenship

A life of ordinary beginnings, extraordinary events

Ellsberg was born in Chicago in 1931. His parents were European Jews who came to America and converted to Christian Science. He attended public schools in Chicago and Detroit and won a scholarship to Harvard, where he graduated summa cum laude in 1952 and won a Marshall Scholarship to attend the University of Cambridge in England. In 1954 he enlisted in the Marines and was commissioned as an officer, mustering out in 1957 and returning to Harvard to work on his doctoral degree in economics.

While still a graduate student in 1958 he began working for Rand. There, he studied nuclear defense policy, worked on an elaborate plan by which the U.S. could preserve its nuclear forces in the event of a first strike by the Soviet Unionand saw war plans drawn up in that era for striking the USSR and China. In 2017 he published a book about this phase of his career called The Doomsday Machine. In 2021, Ellsberg released documents he had from that period because he said he was concerned about mounting tensions between the U.S. and China.

Ellsberg was married twice, the first time to the daughter of a brigadier general in the Marine Corps. The couple divorced in 1965. Five years later, Ellsberg married Patricia Marx, the daughter of a wealthy toy manufacturer, Louis Marx.

NPR researchers Katie Daugert and Barclay Walsh contributed to this report.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.