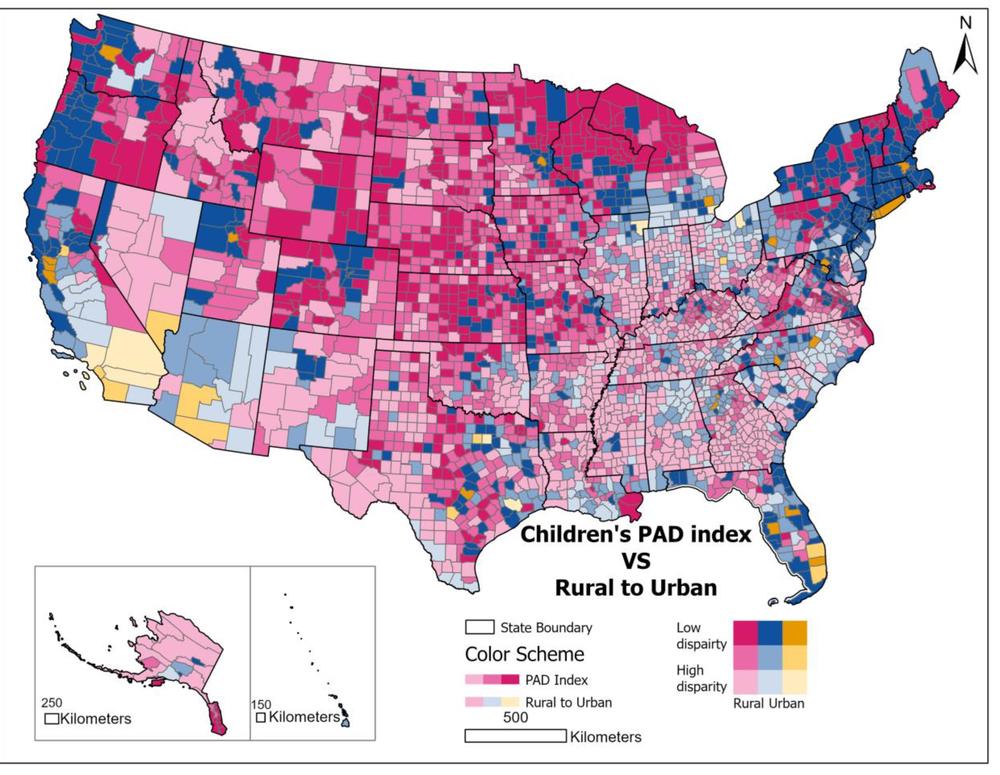

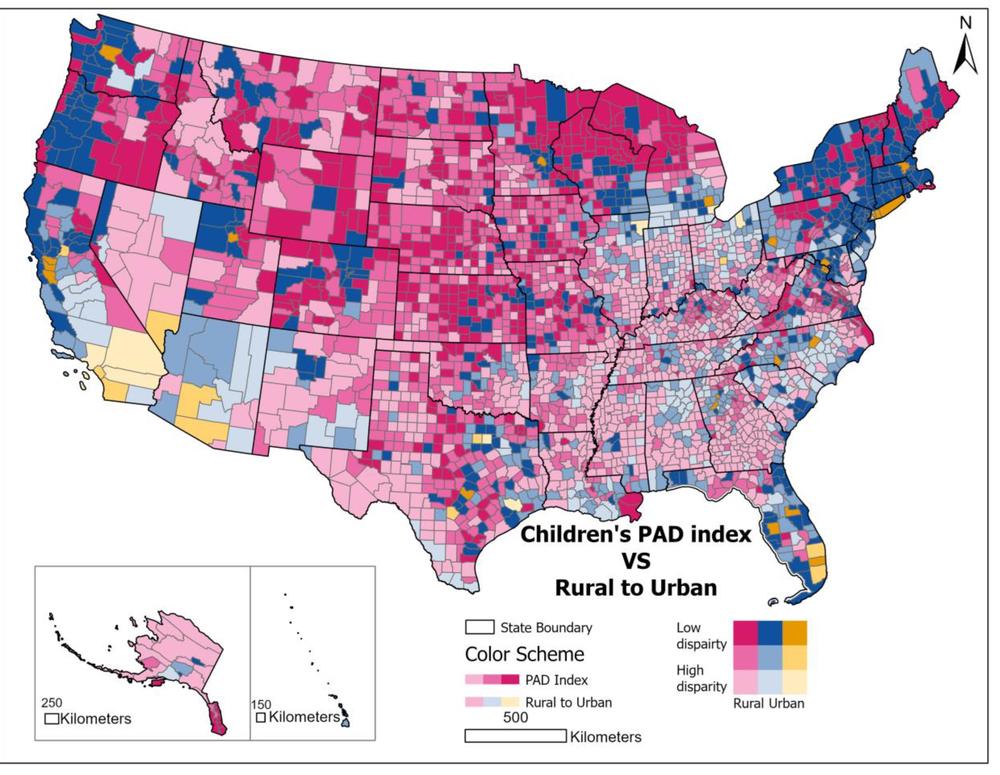

Caption

A comparison of Physical Activity Disparity in urban and rural countines in the U.S.

Credit: International Journal of Geo-Information

Physical activity is vital for children’s health. But a recent study out of the University of Georgia shows there are disparities in access to places where kids can play. Trends from the study show some of the highest disparities are in rural counties.

Lan Mu, professor at the University of Georgia’s Department of Geography, said for the study her team looked at national benchmarks from the National Recreation and Park Association, which recommends about 11 acres of parkland per 1,000 residents.

But Mu said the team realized access to a park doesn’t solve the problem of disparity on its own. So her team developed an index to numerically measure "physical activity disparity."

A comparison of Physical Activity Disparity in urban and rural countines in the U.S.

“So in our research we want to consider the physical activity environment,” said Jue Yang, a Ph.D. student with UGA’s Department of Geography. The study was also co-authored by Janani Rajbhandari-Thapa, an associate professor in UGA’s College of Public Health.

How people feel about spaces for play is one of those metrics.

At Amerson River Park in Macon, Natasha Rodriguez sits at a picnic table while her kids run around. She says the park checks a lot of boxes.

“Do I have somewhere to sit?" Rodriguez said. "Sometimes I like to barbecue. And can the kids play? You know, as long as they could play. Is there water? I love when there's water.”

Measuring physical activity disparity relies on an idea often applied to health care access, Mu said.

“Their basic idea is if something is out there, it doesn't mean people can use it,” Mu said, referring to a 1981 paper published by researchers Roy Penchansky and J. William Thomas. “They proposed a total of five dimensions, or five A's.”

The five A’s are accessibility, availability, accommodation, acceptability and affordability. So that includes factors like the diversity of activities available at a park, crime rates in the area, environmental hazards and people’s opinions about a park.

At Tattnall Square Park across town, Shalondra Barbour watches her young niece and nephew on the playground. She said this park is in a convenient location and feels safe.

“My son, they hang out,” Barbour said about her older son and his friends. “They come walking to be able to have a little free time. So it's a definite peace of mind knowing that it's safe.”

Using the five A’s, Mu said they quantified 41 counties in Georgia as play deserts, or places with high physical activity disparity. Bibb County isn’t one of them — it has average disparities.

Mu said 80% of play deserts are in rural counties.

But Mu said affordable land and lower density means rural counties have huge potential, if policy makers can also consider amenity availability, and how close parks are to families that need them.

“The affordability and acceptability … that count is relatively low,” Mu said about rural counties. For affordability, the study takes into account poverty rates and unemployment levels, which likely brings up disparity rates in rural counties.

Mu said overall, she hopes studies like this can encourage better decision making about where and how we build spaces for play.

“Behavior, your activity, your healthy diet, that's something you can control, but only at the individual level,” Mu said. “But environment is something that we can do for our entire society, for everyone.”

And it’s possible that better physical activity environments can help result in better health outcomes.