Section Branding

Header Content

Jimmy Carter’s work for women’s rights is a lasting centerpiece of his legacy

Primary Content

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was originally published March 2023, after former President Jimmy Carter had been in hospice care for several weeks. Carter died Dec. 29 in Plains, Ga.

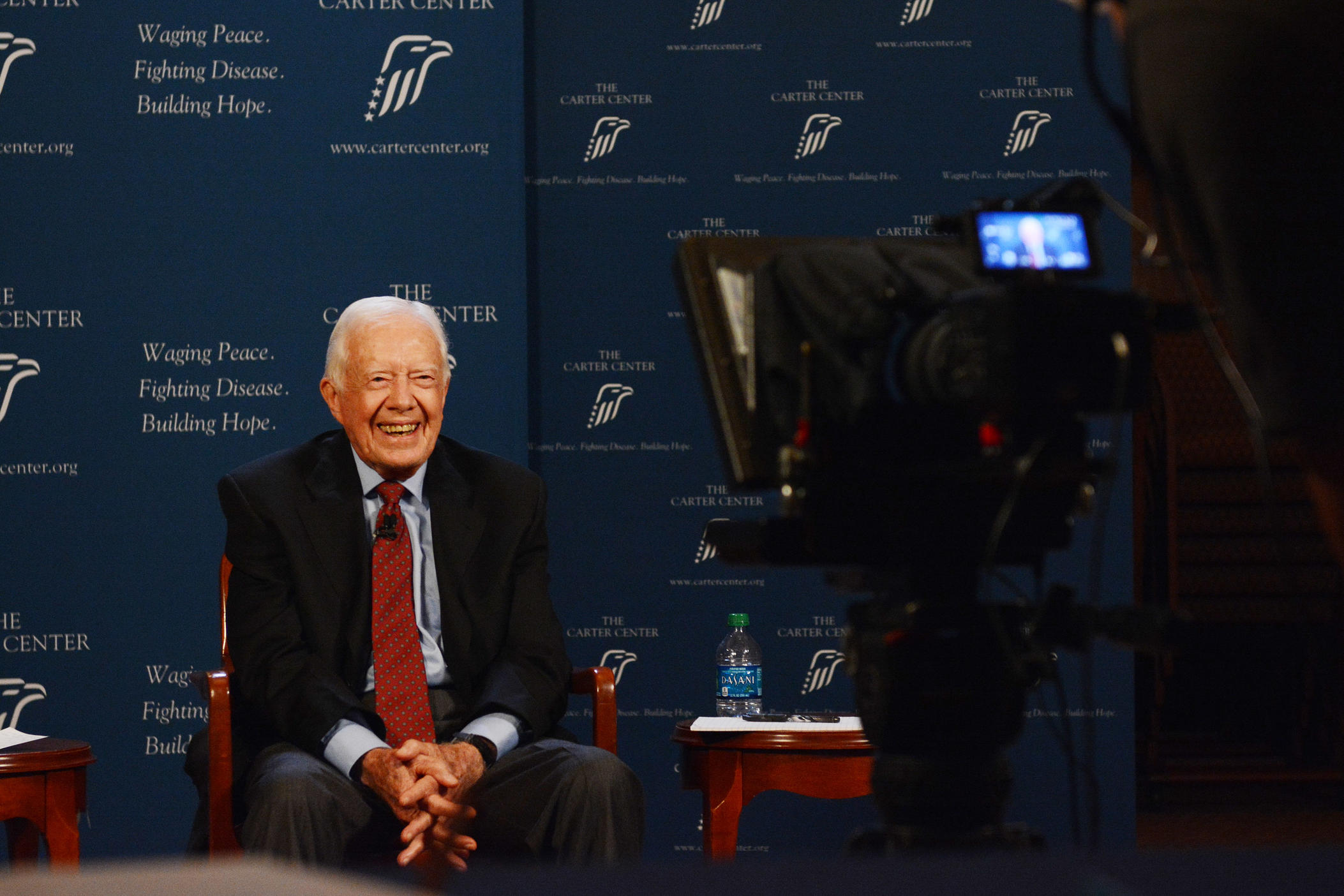

In May 2015, a few months before his 91st birthday, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter appeared at a TED Women conference and gave a substantive 16-minute speech without notes. He landed a timely joke borrowed from a New Yorker cartoon about ex-presidents and casually mentioned the 145 countries he and his wife, Rosalynn, visited in their seven decades as public figures.

Then the tenor of his remarks became serious.

“Knowing the world as I do, I can tell you without any equivocation that the No. 1 abuse of human rights on Earth, strangely not addressed quite often, is the abuse of women and girls,” he began, before calling out religious hypocrisy, systematic gender-based violence and misleading laws about sex work.

“Scriptures are misinterpreted to keep men in an ascendant position,” he said, later summoning women in the audience to check their husbands’ perceived superiority, because “the average man really doesn’t care. Even though they say, ‘I’m against discrimination against girls and women,’" he said, "they enjoy a privileged position.”

Arriving between the promotion of his 2014 book, A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence and Power, and an August 2015 melanoma diagnosis that seemed it might be his undoing, the TED talk marked a pivotal point in the arc of Carter’s human rights work. At a time when the United Nations and NGOs such as Atlanta-based CARE touted women’s empowerment as a means of tackling the root causes of poverty, war and disease, Carter shone because he had worked on those issues at the Carter Center and across his career; commanding a stage in the age of memes meant this nonagenarian was not a relic from a past century but a relevant voice in the discussion.

“He was absolutely flawless as a speaker,” said TED Women founder Pat Mitchell, a fellow Georgian and journalist who was the first woman president and CEO of PBS and served as a White House correspondent during the Carter administration.

“He knew this was a particularly engaged global community of women that he could take this message to,” Mitchell said. “He spoke from his heart, as he always does. There wasn't a dry eye in the room.”

Mitchell said Carter was eager to right the inequalities he’d seen across the decades, especially in rural Georgia and within the Southern Baptist tradition, which he mentioned in his speech for its barring of women from leadership roles.

"‘You and I understand the language of the Deep South,’" Mitchell remembered Carter saying to her. “Because [he and I] grew up on cotton and peanut farms a hundred miles apart — and in South Georgia, that's not a big distance.”

"I was raised in a Baptist church, but not like his," she said. “His church was so influenced by his presence. Mine was the kind of strict religious [environment] that I had to escape as soon as I could. But we talked about it, how strong his faith has been throughout his life. And, you know, there is something about having that [church] foundation. I just couldn't quite take the rules and regulations.”

Long before going viral for his statements about women’s rights, Jimmy Carter challenged the status quo of his religion’s treatment of women. For decades, he taught Sunday School at Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Ga., but distanced himself from the Southern Baptist Convention in 2000 with a letter deriding the convention’s sexist practices.

In 2009, he was back in the news with a not-too-coincidental reference to a song by Georgia band R.E.M. in the title of his essay, “Losing My Religion for Equality.” In that piece, Carter wrote on behalf of a group of independent global leaders including Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu and known as The Elders, hoping to convince imams and pastors and rabbis alike to “change the harmful teachings and practices, no matter how ingrained, which justify discrimination against women.”

In 2014, Carter told The Economist, “Jesus Christ never deviated from one standard — and that was that women are equal to men in every way.” Subsequently, Carter’s own church congregation amended its bylaws to use gender-neutral language. He and Rosalynn are still members there.

Roots, realizations and accomplishments in office

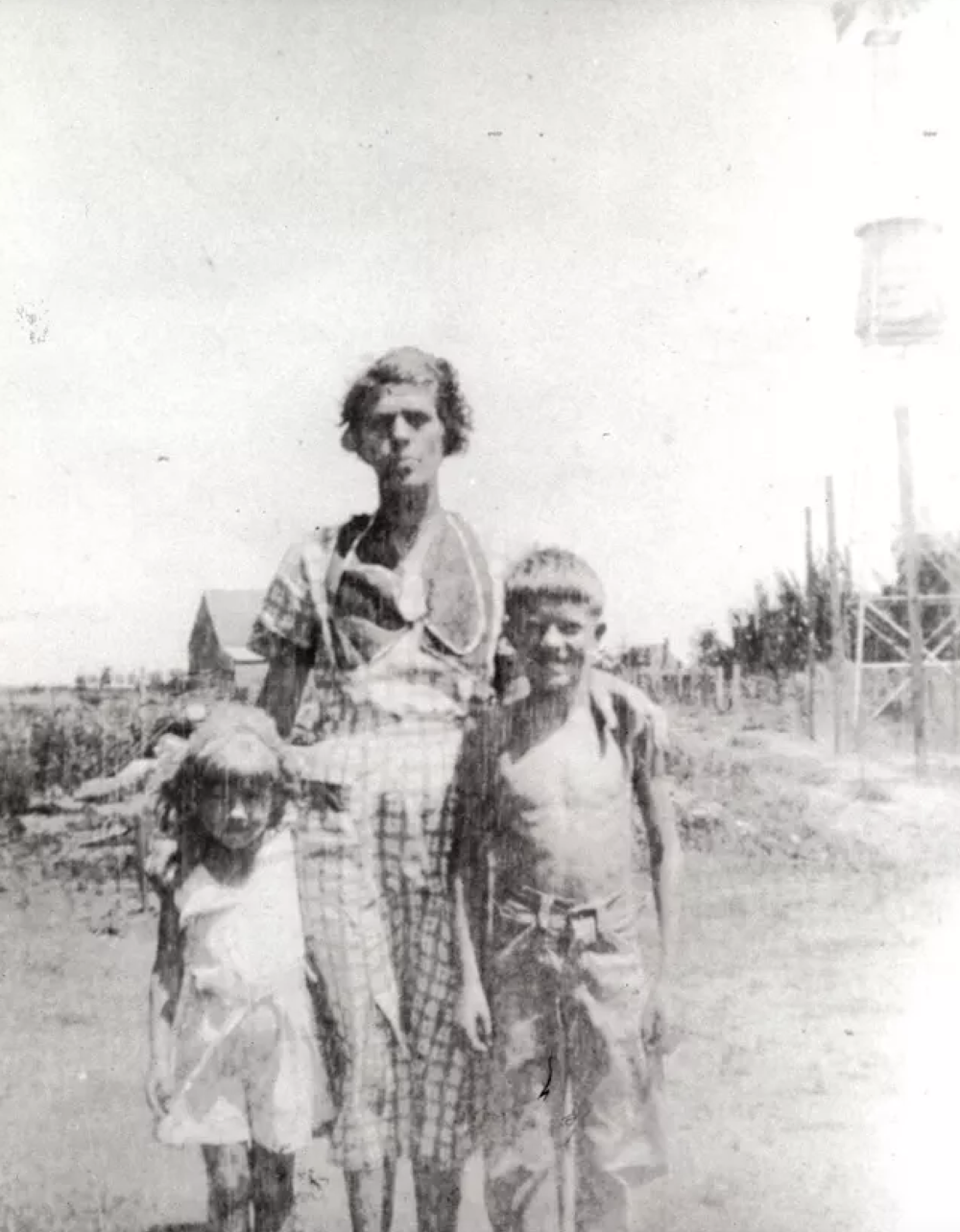

“Twisted interpretations” that deemed women as inferior to men had bothered Carter since childhood, possibly because his father was both a church deacon and a segregationist. But the positive influence of his mother, Lillian, who was trained as a nurse, and Rachel Clark, a Black woman who lived and worked on the Carter family farm and was like a second mother to young Jimmy, shaped his views on women, race, society and the environment and laid the groundwork for the role of women in his political career.

As governor of Georgia and later as president of the United States, Carter prioritized judicial reform, fair treatment of women, hiring of minorities and spoke out against gender and racial discrimination.

In 1977, Carter became the third U.S. president to declare Women’s Day proclamations. He encouraged Rosalynn to pursue her work to reduce stigma around mental health and as first lady she became the first to set up and run her own office in the White House. During his presidency, he appointed women judges to the federal bench. And 43 years ago in March 1980, Jimmy Carter issued a presidential proclamation declaring Women's History Week.

The Carter Center and ‘public worries’ about human rights

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter formed the Carter Center in 1982 to fight disease and promote peace and human rights, basing their outreach on the principles of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as the Center expanded programs in 80 countries. Carter had celebrated the 30th anniversary of the document while in the White House, and it has played a key role in his post-presidency and the Carter Center’s problem solving across differing religions and cultures.

“At meetings, he would say, ‘I've got one,’ and held up a copy of the UDHR. ‘Everybody, go get your Universal Declaration,’” said Karin Ryan, Senior Policy Advisor on Human Rights and Special Representative on Women and Girls for the Carter Center. “He said, ‘You know, whenever I read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, I have the same feeling as when I read my Bible.’”

Ryan said the urgency of Jimmy Carter’s work on women’s rights increased after the Gulf War in the 1990s and continued in the war on terror, when Carter began publicly expressing his worries about human rights violations.

“The '90s were sort of this building decade post-Cold War, with an upward trajectory of improving human rights,” Ryan said. “After 9/11, there was this dramatic shift, because suddenly the human rights norms were being cast aside.”

Ryan said Carter’s op-eds opposing the Iraq War and prisoners at Guantanamo, and his series of books including Our Endangered Values: America's Moral Crisis in 2005, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid in 2006, and We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land: A Plan That Will Work in 2009, were integral to the Carter Center’s work for women’s rights, because “the normalization of violence manifests itself in violence against women.”

This led the Carter Center to assemble forums for women leaders and advocates to create solutions that countered the uptick in violence against women, eventually resulting in Carter’s A Call to Action, as well as a famous CNN interview (‘Women’s rights are the fight of my life,’ Carter told the network) and the 2015 TED Women talk.

The ‘Nobel license’ and 21st-century change

Jimmy Carter’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize at 78 in 2002 also pushed his work for women's rights into specific actionable partnerships, said Mary Robinson, the first woman president of Ireland and former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Robinson first met Carter at a Trilateral Commission meeting in 1973 and has been a stalwart partner in his peace and human rights work and as a fellow member of The Elders. During Carter’s active years with the organization (2007-2016), he and Robinson traveled to North Korea and Jerusalem among other trips; Robinson also appeared with him at an Elders forum at the Carter Center in 2014.

“After Carter got the Nobel Peace Prize, I think he felt he had a Nobel license to be the champion of human rights and women's rights that he always wanted to be,” she said. “It was as if that door was fully open now, and he was probably the most outspoken on women's rights, more than myself and the other women Elders.”

Whether it was stopping early child marriages, putting an end to genital cutting, or ending systemic violence against women, Carter has never been content to let up, Robinson said.

“He has kept saying, ‘We must do more,’” she said.

The pendulum swings again

Jimmy Carter beat cancer in 2016 and has continued his work on women’s rights, disease eradication, democracy and mental health with the Carter Center. He gave up teaching Sunday school in 2019 after a few falls, then COVID-19 made extensive travel difficult. Carter is currently receiving hospice care at home in Plains, and with the arrival of International Women’s Day 2023 comes the opportunity to reflect on his life and contributions.

The world has changed in many ways since his 2015 TED talk. With the rise of authoritarianism, racism, disinformation, the striking down of Roe v. Wade, state laws enacting new voting measures, banning books and limiting freedoms, some human rights advocates feel like the pendulum is swinging backwards.

That's why it's so important to acknowledge Carter's contributions to furthering women's rights, said Taina Bien-Aimé, Executive Director of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women who is a member of the New York City Commission on Gender Equity and a co-founder of Equality Now.

She said Jimmy Carter’s work is unique. From his signing of the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (“CEDAW”) in 1980 to his meeting with survivors of the sex trade in the years before the pandemic, “he's unmatched in his commitment to understanding of what the system of prostitution is and its link to sex trafficking, and speaking out so clearly and with incredible conviction and vision,” she said.

Carter's lifetime of work is valued around the world, but his past two decades represent an unprecedentedly productive period for any former U.S. president, let alone a leader who is in their 80s and 90s, Mary Robinson said.

“He and I have loved working together on women’s rights, human rights and climate justice because it was seamless,” she said of Carter. “Where do we go from here [with the work]? It’s a difficult time because we don't have the same sense of the universality of human rights. We need to repromote that. We need to make it the case that human rights are not Western rights, Eastern rights, Northern or Southern rights. They are the rights of all individuals.”