Caption

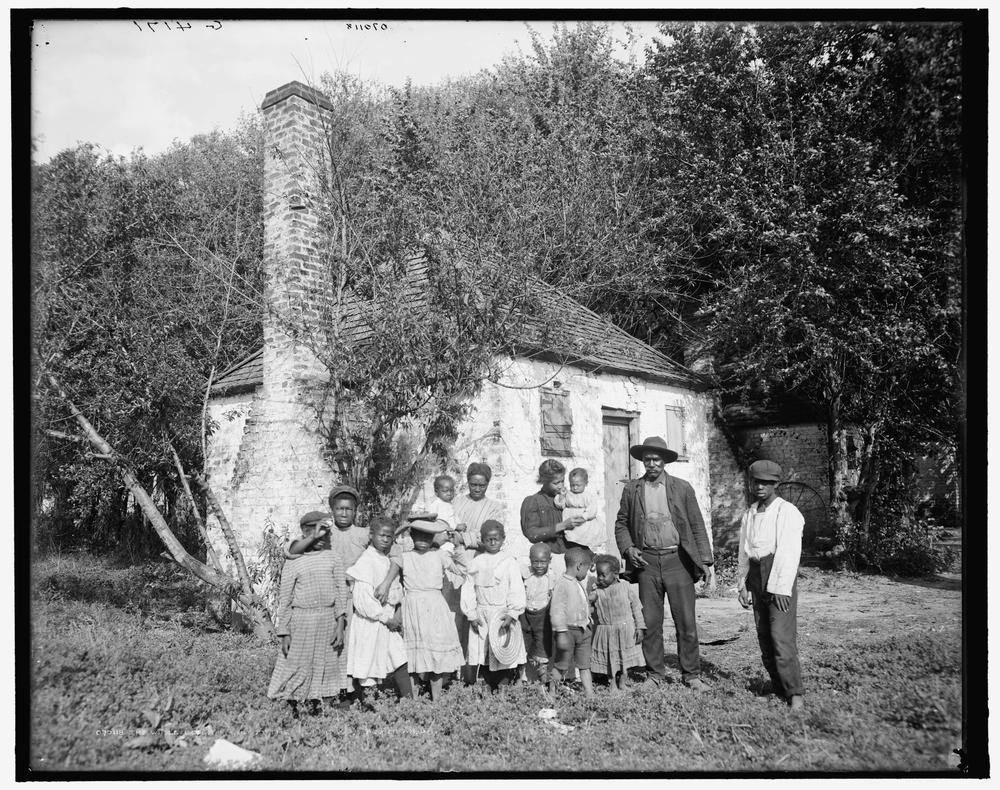

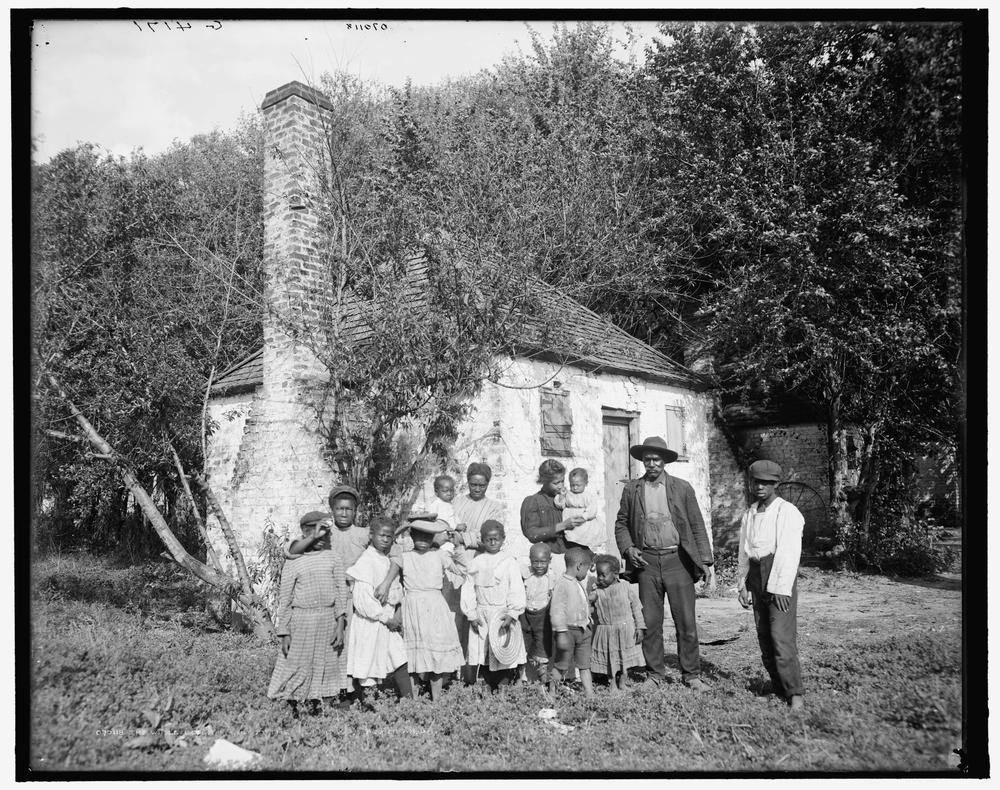

A black family at the Hermitage Plantation in Savannah, a city established partly to bolster slavery.

Credit: Library of Congress

LISTEN: The history of the city of Savannah is bound to the history of slavery in the United States. GPB's Peter Biello speaks with Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative, whose new report at the legacy of slavery through the cities that played leading roles in promoting and enabling it.

A black family at the Hermitage Plantation in Savannah, a city established partly to bolster slavery.

The history of the city of Savannah is bound to the history of slavery in the United States. Enslaved people built much of the city, which was settled in part to prevent enslaved people from South Carolina from fleeing to Florida, where Spanish colonists offered them freedom to weaken the English colonies. A new report from the Equal Justice Initiative looks at the legacy of slavery through the cities that played leading roles in promoting and enabling it. Equal Justice Initiative director Bryan Stevenson spoke with GPB’s Peter Biello.

Peter Biello: So tell us a little bit about this project in particular. Why did you want to view the history of slavery through places like Savannah that played such large, large roles in maintaining it?

Bryan Stevenson: I don't think most Americans know what they should know about the history of slavery in America. I think most schools teach a version of this history that is superficial, that doesn't really get at some really important realities that we're still struggling with today. Slavery in the United States became racialized. It was constructed around a narrative that Black people are not as good as white people, that Black people are somehow inferior, less capable, less worthy. And that ideology of racial hierarchy has continued to haunt our nation for centuries. And so understanding how it was constructed is really important. Places like Savannah are really key to this story because Georgia initially did not authorize slavery. By 1751, however, slavery was legalized and Savannah became a very, very active slave trading space.

Peter Biello: One of the things you pointed out in this report that I found really fascinating was that by the late 18th century, more than three quarters of Chatham County, where Savannah is located, were enslaved Black people. And as you mentioned, there was a portion of that century where slavery was officially illegal. So maybe this is one of those things that you think people don't know enough about, which is that slavery grew even when it was illegal.

Bryan Stevenson: That's right. You know, there was this idea that Georgia would be a place that did not condone human bondage, that would not participate in this horrific slave trade that had created so much death and brutality and horror across the Americas. But that quickly gave in to the aspirations of planters and white landowners who wanted to make profits. And so the city, created in the 1730s, quickly became a place overrun by the desire for wealth by slavers.

Peter Biello: One thing that struck me in this report was that Black people were enslaved not just by individuals on plantations, but also by the Savannah city government. Can you can you tell us a little bit about that?

Bryan Stevenson: In most of the country, enslavement became a private enterprise where private landowners would employ or engage traffickers and they would buy enslaved people at auctions. But there were places where governments got involved as well. And that certainly happened in Savannah. There was a kind of urban enslavement that took place in Savannah, where city officials used enslaved people to clean dead animals and debris off the streets to clear weeds and brush in public spaces. They were used to facilitate the growth of this city. So much of the beauty of Savannah dating back centuries was created by the labor of enslaved people, and that made the government an active partner and active player in the slave trade. That's why you saw so much commercial activity around slavery. You had a very supportive governance there.

Peter Biello: What do you hope people take away from this project?

Bryan Stevenson: I hope they take away from this that we we ought to have the courage to talk honestly about our history. We don't have to fear history. Sometimes I think what people hear me or others talking about slavery or lynching or segregation, they think that we want to punish America with this history. I have no interest in punishment. My interest is liberation. I genuinely believe that there is something that feels more like freedom, feels more like equality, feels more like justice waiting for us in this country. But I don't think we can get there if we're unwilling to talk honestly about the histories and the practices and the experiences that have undermined that quest for freedom, that have compromised that quest for justice and equality, which is why I think reckoning with history is so important. It can be intimidating, it can be unnerving. But I also think it can be unbelievably empowering.