Caption

Kinder Morgan's Elba Island LNG facility sits on the banks of the Savannah River.

Credit: Jeffery M. Glover/ The Current

Kinder Morgan's Elba Island LNG facility sits on the banks of the Savannah River.

Nick Sullivan, The Current

For decades Tybee resident Gordon Matthews drove past Elba Island on his way towards Savannah. The sky-blue storage tanks, which first went operational in the 1970s, contain liquefied natural gas and tower above the Savannah River. They’ve always piqued his interest.

New safety questions arose in 2019 when Elba became one of seven LNG export facilities in the nation. A June 8 explosion at a major Texas LNG exporter heightened Matthews’ worries.

Now, as he drives back and forth to Tybee, Matthews wonders what might happen if gas escaped from those storage units and drifted across Chatham County and what economic blow the city could take in the event of a significant incident such as occurred at the Texas export facility.

“Most people don’t even know what those blue tanks are,” Matthews said. “If there is a leak, it could all be over in 15 minutes.”

The Texas pipeline explosion remains under investigation, but it serves as a reminder that despite the LNG industry’s strong safety record, accidents do happen. Risks have shifted at Elba as the facility moves focus from imports to exports. However, experts say evolving hazards are not widely understood and the U.S. regulatory body that oversees LNG facilities has been slow to revise its standards.

The company that operates Elba Island says its facility is operating safely and the company has multiple plans in place for potential mishaps or incidents.

“Our Elba Island facility was constructed in accordance with all safety and environmental requirements by its regulators,” Katherine Hill, the spokesperson for Texas-based Kinder Morgan, said in an email response. “We continue to operate the facility to meet the requirements of our federal and state regulators.”

LNG is natural gas that was cooled at extreme temperatures and liquefied for ease of transport and storage. When ready to be used as energy, it is returned to its gaseous state and burned to produce electricity and heat.

LNG has a remarkably strong safety record compared to other fuels regulated by the Pipelines and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, a federal agency that regulates energy transport systems. In the last ten years 32 LNG “incidents” of varying severity have been reported to the agency, with only one reported injury. [That number does not include the recent Texas explosion at the facility operated by Freeport LNG.]

One of those incidents occurred at Elba Island, a facility owned and operated by Kinder Morgan and a division of Blackstone. The incident involved refrigerant catching fire, although it was quickly contained.

Chatham Emergency Management Agency worked with Elba in developing its emergency plan and is prepared to react in the case of an explosion, according to agency Director Dennis Jones. Jones directed further questions regarding Elba’s emergency plan to Kinder Morgan.

The company did not answer questions posed about what might trigger its emergency response plan. However, the plan itself says no public areas containing residences, schools, hospitals, parks or other sensitive areas would be impacted in the unlikely event of a spill or release. “Accordingly, there should be no reason for evacuation of public areas adjacent to Elba Island,” the plan says.

This guidance stands in stark contrast to findings from a 2004 study contracted by Chatham County and conducted by Chuck Watson, the Savannah-based founder of Enki Research. Enki works with international agencies and NGOs to forecast the impact of hazardous events.

“The odds of an accident, to be clear, are quite low,” Watson said. “The problem is if you have an accident, the consequences are quite high.”

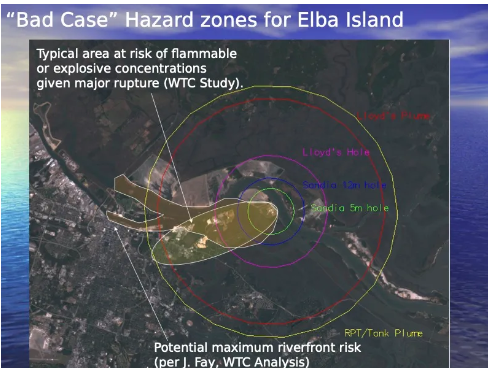

The 2004 study evaluated Savannah’s potential hazard sites and determined what a “bad-case” scenario might look like for areas surrounding Elba Island, which sits 5 miles downstream from city hall. In the event of a major rupture of a single storage tank or tanker ship, he found that heat from a pool fire could burn exposed skin up to 3-5 miles away.

A presentation slide from Savannah-based hazards expert Chuck Watson shows the scenarios for various ruptures in tanks or ships. The Sandia and Lloyds studies are generic, whereas the WTC and Fay studies consider local weather and topographic conditions.

Watson also noted concerns about Elba’s proximity to tourist hub Tybee Island and its location downstream from the port of Savannah, one of the busiest seaports in the country.

Company spokesperson Hill did not respond to questions raised by Watson’s study.

Causton Bluff, a neighborhood situated just two miles south of Elba, is well within the range of potential thermal impact, according to Watson’s bad-case scenario. But unlike Tybee resident Matthews, representatives of the Causton Bluff Homeowners Association said their neighborhood pays little mind to the facility down the road, even describing it as a “good neighbor.”

Causton Bluff HOA Secretary and Treasurer Albert Parnell said he lived in his home for several years before learning the facility’s purpose. To his recollection, LNG has never been mentioned in an HOA email or discussed at a meeting in his three years with the association.

“The ships come in all the time, which, frankly, is one of the reasons we like it,” Parnell said. “We like watching the cargo ships go by.”

The United States had a single LNG export terminal prior to 2016, but with the fracking boom it is now one of the world’s top nations selling the fuel abroad. Elba’s first of 10 liquefaction units went into service three years ago.

In America, safety measures have long been based on the belief that natural gas leaks posed little explosive threat when unconfined. Since natural gas clouds are largely lighter-than-air methane, they quickly dissipate in open air, as is historically the case at import terminals.

But the process of liquefaction changed this understanding, according to Jerry Havens, an emeritus distinguished professor of engineering at the University of Arkansas. LNG export terminals carry additional risk due to the large quantities of refrigerants used in the process. These refrigerants often contain heavier-than-air hydrocarbons, meaning in the case of a gas leak, weighed-down vapor is more likely to gather into large, low-to-the-ground clouds before dispersing. If they encounter a spark, a resulting explosion could be disastrous.

The U.S. pipeline regulatory agency commissioned an independent British regulator to study recent vapor cloud explosions similar to what could be found at LNG export terminals. Graham Atkinson, the principal scientist overseeing the work, discussed the study at a 2016 LNG workshop held by U.S. government officials. He found that many of the worst incidents occurred in low-wind or calm conditions.

“In calm weather ignition is highly likely if the leak is not isolated quickly,” Atkinson said in an email interview. “It is hard to avoid the conclusion that if an ordinary gasoline depot, LPG installation (or LNG facility) has the misfortune to suffer a major loss of containment in conditions that lead to one of these very large clouds, then there is a relatively high probability that this will lead to a severe explosion.”

Havens, who attended the 2016 workshop, has been pushing for regulatory change ever since. However, the U.S. pipeline regulator has not updated its standards regarding uncontained vapor cloud explosions, nor has it adjusted its hazard modeling, which was used when Elba opened up for exports.

Elba’s Environmental Assessment meets U.S. regulatory guidelines, according to a spokesperson for the pipeline regulating agency. Elba calculates its blast wave hazard using one pound per square inch (psi) at the site’s boundary line, a level that has potential to damage buildings and cause injuries from projectiles. Psi is a measure of severity.

This number is at least 10 times smaller than the severity depicted in real-world case studies presented at the workshop, which Havens said “have a demonstrated capability of destroying an entire plant and impacting the offsite public because of cascading failures.”

Put simply, the modeling does not consider realistically severe accidents that could pose a major hazard to the surrounding community.

Still, when calculating risk, independent engineers have run into an important limitation. The risk model used by the U.S. pipeline regulator is proprietary, challenging engineers’ ability to review or corroborate industry calculations.

When asked for comment, Hill did not say whether Kinder Morgan was aware of the concerns posed at the workshop or has sought to address them.

On June 3, Havens filed a petition with the pipeline regulator requesting the agency update its guidelines in response to the research presented in 2016. He has yet to hear back.

“We are ignoring the warnings that were given in the workshop,” Havens said.

The regulatory agency, meanwhile, says it continues to research risk models for LNG with an eye to revising its guidelines. One such project is studying vapor cloud explosions in calm conditions. Another is exploring the cascading effects from flammable vapor cloud explosions — what Watson would consider a worst-case scenario. Following recommendations from these projects, the regulator “will issue further guidance regarding VCEs,” according to an agency spokesman.

Roughly two dozen export terminals, including Elba Island, have been built or approved since the 2016 workshop. These sites predate further vapor cloud explosion studies.

“The risk is not as bad as you’ll hear from a lot of environmentalists and environmental groups, but it’s not nearly as low as you’ll hear from the industry,” Watson said. “Truth is always somewhere in the middle.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, providing in-depth journalism for Coastal Georgia.