Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Today: Remembering Max Cleland, a life strong in the broken places

Primary Content

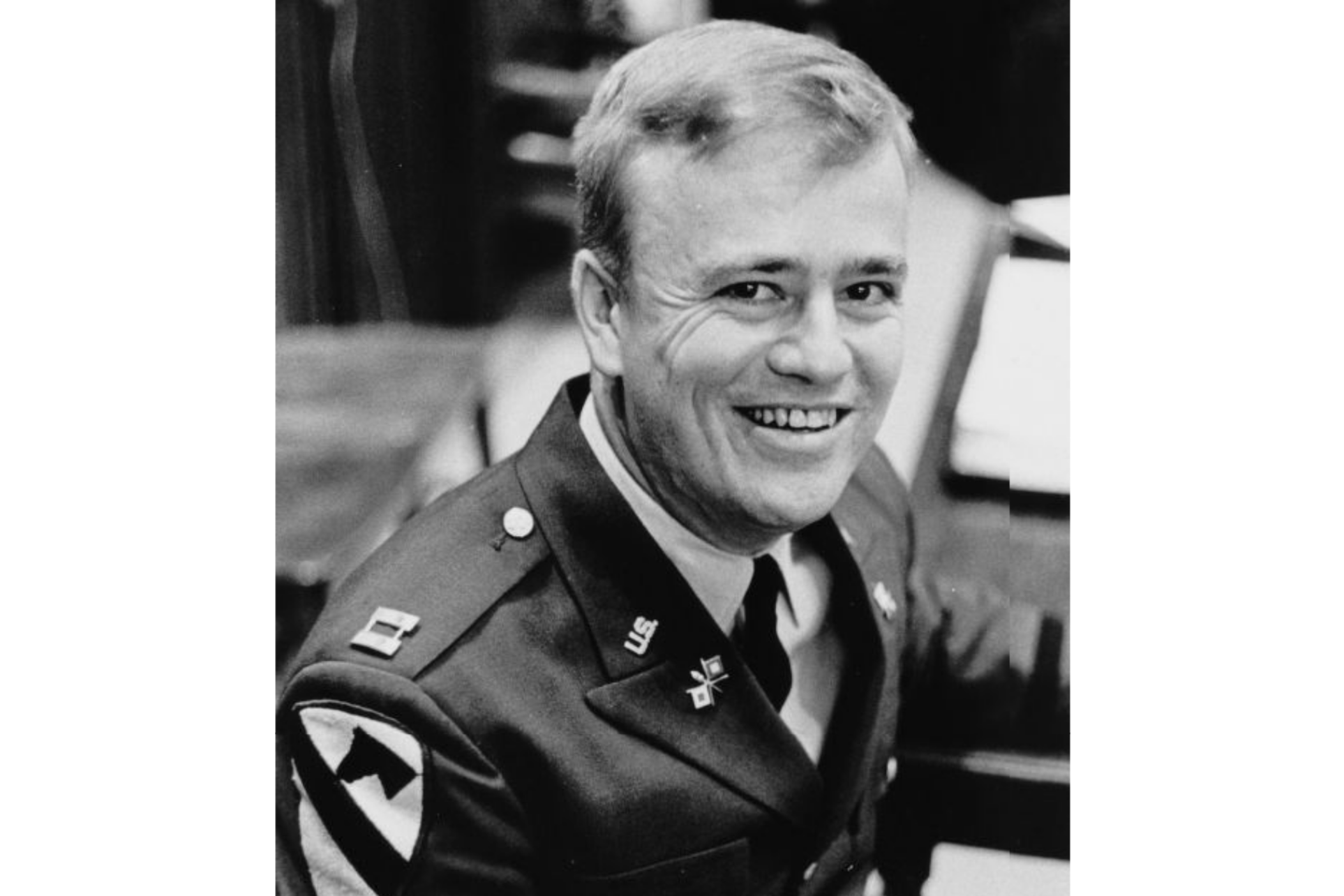

This week, Georgians around the state are remembering Max Cleland. He died of congestive heart failure at his home in Atlanta on Tuesday. He was 79. Cleland was a Democrat and lifelong public servant in a variety of roles, including U.S. senator and head of the Veterans Administration under President Jimmy Carter. Jim Galloway, a now-retired Atlanta Journal-Constitution journalist, says Cleland’s politics were influenced by his military service. He lost three limbs in the Vietnam War. Georgia Today explores Cleland's life and legacy with Galloway, who also knew Cleland as a friend.

RELATED: Former VA administrator and Georgia senator Max Cleland dies at home

TRANSCRIPT

Steve Fennessy: I'm Steve Fennessy. This is Georgia Today. On the podcast this week: remembering Max Cleland. Cleland died Tuesday of congestive heart failure at his home in Atlanta. He was 79. Cleland, a Democrat, dedicated his life to public service as head of Veterans Affairs under President Carter, as Georgia's secretary of state, as a U.S. senator. Cleland, who lost three limbs in Vietnam, was a passionate advocate for veterans. He went on to champion the recognition of post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans. For more on Cleland, the public figure and the man, I'm joined by Jim Galloway. Jim covered Max Cleland as a journalist for many years and knew him well. Jim, welcome, and I'm sorry for the loss of your friend.

Jim Galloway: Thank you very much, Steve. He was a great man and he’s a tremendous loss for the state.

Steve Fennessy: When was the last time that you'd been in touch with him?

Jim Galloway: I dropped by his house on Thursday — last Thursday week. I usually visit him once a week. I mean, he's been growing ever weaker. He always kind of relied on me for, for the latest political news. So I read him a column written by Patricia Murphy over at the Atlanta Constitution. She took my place as a political columnist. It was all about Gov. Brian Kemp possibly being primaried by David Perdue. So he was very interested. The exact words that he mouthed was, “Wow.”

Steve Fennessy: Well, I'm curious. I mean, having visited him once a week. What was his take on where things have gone politically in Georgia?

Jim Galloway: He was very disappointed by his 2002 defeat by Saxby Chambliss, and you had Republicans calling into question his patriotism. And — and for, for a man who — who — who lost two legs and his right arm in Vietnam, that was hard to swallow.

Steve Fennessy: Well, much of the coverage of his death, of course, is mentioning prominently those attack ads that ran against him when he was running for reelection in 2002 —unsuccessfully, as it turned out. But — I want to talk about that, but first, I'd like our listeners to better understand Max Cleland as someone who withstood almost unimaginable injuries in Vietnam as a young man. What — what exactly happened to him on that day in April 1968?

Jim Galloway: It was just a few days after Martin Luther King had been assassinated on the other side of the world. His team had just disembarked from a helicopter, and he — he saw a grenade on the ground, a live grenade.

[News tape] WSB: After a private had dropped a grenade getting out of a helicopter. Cleland went to grab it to toss it away from other soldiers, but it went off — taking three of his limbs with it.

Jim Galloway: It very nearly killed him right there. His right arm and right leg were — were severed immediately. He soon lost his left leg. A Marine took off his ammunition belt and tied it around his left leg, which kind of saved him from bleeding to death.

Steve Fennessy: Now, Sen. Cleland, he thought for years, didn't he, that that grenade had been his, that he had dropped it somehow?

Jim Galloway: This is the thing about Max is, he was not a hero of Vietnam and he never considered himself a hero of Vietnam.

[Tape] Max Cleland: And I didn't want to avoid the war of my generation. I mean, I knew this was going to be big. And as a history major, you know, these defining moments in American history come along every now and then. And if you really want to learn about it, you really hope to be part of America in the future. You better get in there and understand it so you can be a good leader afterward.

Jim Galloway: The Marine who saved his life was the one who told him — I think it was in 1999 — that note it was that the grenade didn't fall off Max's belt. It fell off the belt of the newbie. That was a small comfort.

Steve Fennessy: So he comes home after months of recovery now at Walter Reed Hospital outside Washington.

Jim Galloway: Years, yes.

Steve Fennessy: He loses both his legs. He loses his right arm. And then he's back in his parents’ house and he's still just a young man and in his late 20s and he's looking around. And I mean, I saw him in a quote to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution a few years ago saying to himself, “I've got no job offers. I've got no girlfriend, no future, no hope.” What did he do?

Jim Galloway: He was always interested in politics from his college years. I mean, he was, in a way, he was kind of the consummate Southern politician in that he conceived of military service as the way to get there. So he stuck with that plan. He won a seat in the state Senate, and I think at the time he was the youngest member there. He did it on a pair of artificial legs and crutches.

Steve Fennessy: So his interest in politics predated his service in the Army. And in fact, he enlisted. He wasn't drafted right?

Jim Galloway: Right. And he was ROTC out of Stetson University in Florida. Then I think his later service came in 1965 or so, his DC experience came then.

Steve Fennessy: So after his injuries, after the long recovery, I'd like just an idea of how difficult it was all the way for the next 50-plus years of just the normal things that we take for granted. Getting out of bed in the morning. Preparing yourself a meal. Taking a shower. What was that like for him?

Jim Galloway: It was very, very hard, and the logistics of his life became so very important. Very quickly, he found himself in a motorized wheelchair. He lived in an apartment in Buckhead, right off Peachtree Road. When he was ready to go to bed, he would pump that wheelchair up against his bed so he could jump into it at night. The chair would be there ready and waiting for him, properly spaced in the morning when he when he wanted to get out of bed. And he did all of that with the left arm in ’82. He tried to run for lieutenant governor, got beat by Zell Miller and instead went up to Washington, D.C., for a job with the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, and he drove himself.

Steve Fennessy: I think it's important to also talk about his tenure as head of the Veterans Administration under President Carter. He was very young at that time. What was he, like 34, when he was appointed to be in charge of the entire Veterans Administration?

Jim Galloway: Right. That wasn't a Cabinet position at that point, but it was one of the first actions that Jimmy Carter took as soon as he was sworn in as president. Max was one of the first people in that Oval Office with the president.

Max Cleland: The only thing that I had commanded up to that point had been a platoon in Vietnam. Beyond that, I really had no quote “executive experience.” At that time, the Veterans Administration was bigger than five cabinet level departments combined.

Jim Galloway: Symbolically, it was — you have to remember this was, this was a tremendous move because the Vietnam War was such a rending affair in the United States. And you had, about that same time, you did have John Kerry, for instance, testifying against the war before a Senate committee, and they would later pair up in the U.S. Senate. It was very symbolic. And it got down into some very weedy issues, including something very important called post-traumatic stress syndrome. They didn't have a name for it that, you know, I mean, in World War I, it was called shell shock. It had all sorts of names with bad overtones during World War II and Max was able to push through the concept that this was something real. It wasn't an imaginary illness concocted by people who who just weren't on the ball. He would tell you that PTSD stuck with him throughout his life.

[News tape] WSB: He suffered from PTSD. Outwardly, he was an extrovert who shared a sunny disposition. In 2009, he wrote, “My body, my soul, my spirit and my belief in life itself, stolen from me by the disaster of the Vietnam War. I found solace in attempting to turn my pain into someone else's gain by immersing myself in politics and public service.”

Steve Fennessy: And how did his being very open about those struggles during his time as head of Veterans Affairs help bring that condition more into the spotlight in the mainstream?

Jim Galloway: I think his personal coming out with PTSD happened maybe after 2002, after that defeat. I think he saw himself more as a champion for his fellow service members, as head of what would become the VA.

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: On the MacNeil Lehrer Report in 1978, then-VA Administrator Cleland spoke of the difficulties facing those who had served in that unpopular war.

Max Cleland: I think that part of the problem that we will have with Vietnam veterans is unfortunately the negative image that the war, in a sense, created for us. I am personally committed to making sure that those who have served this country and served it well, particularly the disabled veteran, gets the finest treatment in our hospital system possible.

Steve Fennessy: Jim, you mentioned that you were over to his house a number of times over the years. How did you first come to meet Max Cleland?

Jim Galloway: I think the year was maybe 1990, and Max Cleland invited me to to to lunch somewhere in downtown Atlanta. There was this idea floating around about about establishing a state lottery for college scholarships. What did I think about that? Clearly, Zell had been kind of tossing around the idea and seeing how it would fit, and Max was doing the same thing.

Steve Fennessy: And so he clearly had political ambitions. I mean, he was a politician for his adult life in the state Senate. He was head of the VA, he was secretary of state. So as you came to know him in the 1990s, what was your take on what his ambitions politically for himself were?

Jim Galloway: He was an excellent retail politician. He just loved getting out there and meeting people. In that sense, I compare him a lot to to John Lewis. Both men had their legislative agendas. They had their ambitions of what they wanted to do. Policy wise, both kind of understood that they were symbols of something far greater than themselves.

Steve Fennessy: And in his case, Max Cleland's case, in 1996, he did run and won the U.S. Senate seat from Georgia, succeeding Sam Nunn, right?

Jim Galloway: Succeeding Sam Nunn. And it was a — it was a close run race even then. He did not — in that contest, Max did not win the majority vote. At that point, we didn't have the 50% plus one law in effect. So there was no runoff. He took it by a plurality. It was — it was a close plurality, but it was a majority. As I recall, it was also I think that election was the first one in Georgia where a Democrat would win without winning a majority of the white vote.

Steve Fennessy: And so his Senate term of six years, the first four years were under the Clinton administration, and then the final two were essentially under the George W. Bush administration. And then, of course, we have 9/11 and everything that occurred there right around a year before he was up for reelection. Bring us back to that time and how fraught it was for a Democrat, especially in the South, trying to run to win a seat again.

Jim Galloway: Well, you had, of course, you had George W. Bush. You know, he visited the World Trade Center. His approval rating was very high. There were all these promises that this would be a bipartisan response when it came to going after the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. Max Cleland voted for the war in Iraq. He was under great pressure to do so. He would later say that it was one of the worst decisions of his life. This was when you had Colin Powell, secretary of state, getting up and making a case for the war, the case against Saddam Hussein having weapons of mass destruction. And it turned out not to be so. You also have to remember: One of the things that happened in Georgia politics after 9/11 is that Zell Miller, nominated or sent to the Senate by, by Gov. Roy Barnes — both were Democrats. So Zell Miller, a Democrat, really started backing George W. Bush to the hilt, and it put Max in a very difficult position, particularly when they —when they were dealing with Homeland Security legislation to establish the Homeland Security Department.

Steve Fennessy: So any vote against the president became conflated with a vote against America, in a way.

Jim Galloway: It was a real shift in in how politics is done, and Max and his reelection committee just were not prepared for that. They thought Georgia knew him and he knew Georgia. That's when Republicans went after him for opposing a George Bush policy and threw up those images of Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden.

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: He was elected to the Senate in 1996, but lost reelection a year after 9/11 in a nasty race in which his Republican opponent, who had never served in the military, questioned his patriotism.

[News tape] Roll Call: Max Cleland has voted against the president's vital Homeland Security efforts 11 times. Max Cleland says he has the courage to lead, but the record proves Max Cleland is just misleading.

Steve Fennessy: Up next, how Max Cleland's defeat in 2002 brought him face to face with what he called the black dog of depression. This is Georgia Today. I'm Steve Fennessy.

[BREAK]

Steve Fennessy: You're listening to Georgia Today. I'm Steve Fennessy. I'm joined by Jim Galloway, a longtime journalist at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, as a reporter and editor. Galloway spent years covering Max Cleland, and the two men had a friendship that also extended beyond the news cycle. I remember seeing those ads back in 2002, and I recall my first reaction being “this is going to backfire on the Republicans. They are impugning the patriotism of a triple amputee who suffered these grievous losses defending his country in Vietnam. That's nuts.” And yet I couldn't have been more wrong.

Jim Galloway: Absolutely. And that's why — that’s why the Cleland campaign was slow to respond. You know, they thought those behind Saxby Chambliss — and you can't tie Saxby directly to that ad, I don't think — they thought they were hanging themselves. We had quotes from John McCain, John Kerry back in that day, Bob Kerrey, if you remember, and they were all absolutely appalled. But it became routine just a few years later when John Kerry was running for president.

Steve Fennessy: The Republicans in 2002 kind of run the table. I mean, Sonny Perdue defeats the incumbent Roy Barnes to become the first Republican governor of Georgia in over —well over — a century. What is the impact, personally, I guess emotionally, psychologically, on Max Cleland?

Jim Galloway: And he wrote about this. I mean, he was sent into a tremendous tailspin of depression. This is probably when we started hooking up together a little bit, just as friends. You know, he felt — he felt so wounded. We would often sit down and talk about the, what we call the black dog.

Steve Fennessy: What was the black dog?

Jim Galloway: That was depression. That was the creature that sits on your shoulder and says, “All is lost.”

Steve Fennessy: Where did you fear that that might take him?

Jim Galloway: Oh, I think it's something that you saw that he was working through.

Steve Fennessy: How did he do that?

Jim Galloway: In 2017, Ken Burns had the documentary on Vietnam and the voice you heard on that was that of Max Cleland.

Max Cleland: Victor Frankl, who survived the death camps in World War II, wrote a book called Man's Search for Meaning. You know, to live is to suffer. To survive is to find meaning in suffering. And for those of us who suffered because of Vietnam, that's been our quest ever since.

Jim Galloway: He was very big into philosophy, especially uplifting philosophy. Maybe two years ago, maybe three, we went about the process of replacing Max's bed, and he had cut off the legs so that it would do would match the height of his wheelchair so he could get in and out of it all right. So he asked me to find a way to carve into wood a quote from Patrick Overton. And the quote is: when we walk to the edge of all the light we have and take the step into the darkness of the unknown, we must believe that one of two things will happen. There will be something solid for us to stand on or we will be taught to fly.

I had it carved on a piece of his bed frame for him. I did have one thing added to the back of the piece. And those that — those were the letters “MCSH.” Max Cleland slept here. Max had a great sense of humor. He loved it.

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: Bound to a wheelchair most of his adult life, Cleland was gregarious and upbeat. Known for wearing a Mickey Mouse watch as a reminder, he said…

[News tape]: “Morning, senator!” “Good day to go to work.”

[News tape] PBS NewsHour: …not to take life too seriously.

Steve Fennessy: We're talking about sort of those dark days after his loss in 2002, and I understand that as part of his recovery, he actually attended meetings at Walter Reed with other other people who were going through post-traumatic stress. Did he ever talk about that?

Jim Galloway: Well, he had a group here in Atlanta, too. There was a tight circle of veterans that he would connect with here.

Steve Fennessy: What did that mean to him?

Jim Galloway: I was never in the military, and it was important for him to be around people who did understand that language. And I think the continued camaraderie helped him.

Steve Fennessy: Jimmy, you knew Max Cleland for many, many years. As we reflect on him and his life now, what's sort of the the most prevailing memory or thought that you have about him that will stick with you forever?

Jim Galloway: It's the image of a fellow who would never give up. I mean, after he lost the Senate, he went to work for the Export — Import Export Bank. He was — he was head of the Battlefield Memorial Association. He wanted to go out on a high note. His hope was that Hillary Clinton would be elected president in 2016, which would allow him to preside over the 75th anniversary of D-Day at Normandy. That didn't happen. But he kept on going. You know, he was the kind of fellow who lost a lot in 1968 and decided he was going to lose much more. He was gonna live it out. The physical image of Max Cleland that I'm going to have in, in my head, the rest of my life is that of a 75-year-old man with one arm hauling himself into his own Cadillac and out of it again. It was an everyday thing. And I just don't think that people realize the heroism that was in that.

Steve Fennessy: I've been speaking with Jim Galloway. Max Cleland is set to be buried in a cemetery that during his career he helped to establish. His plot sits next to his parents' at Georgia National Cemetery in Canton.

Georgia Today is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Jess Mador is our producer. Our engineers are Jesse Nighswonger and Jake Cook. You can keep up with Georgia Today by subscribing to the show at GPB.org or anywhere you get podcasts. Thanks for listening. See you next week.