Caption

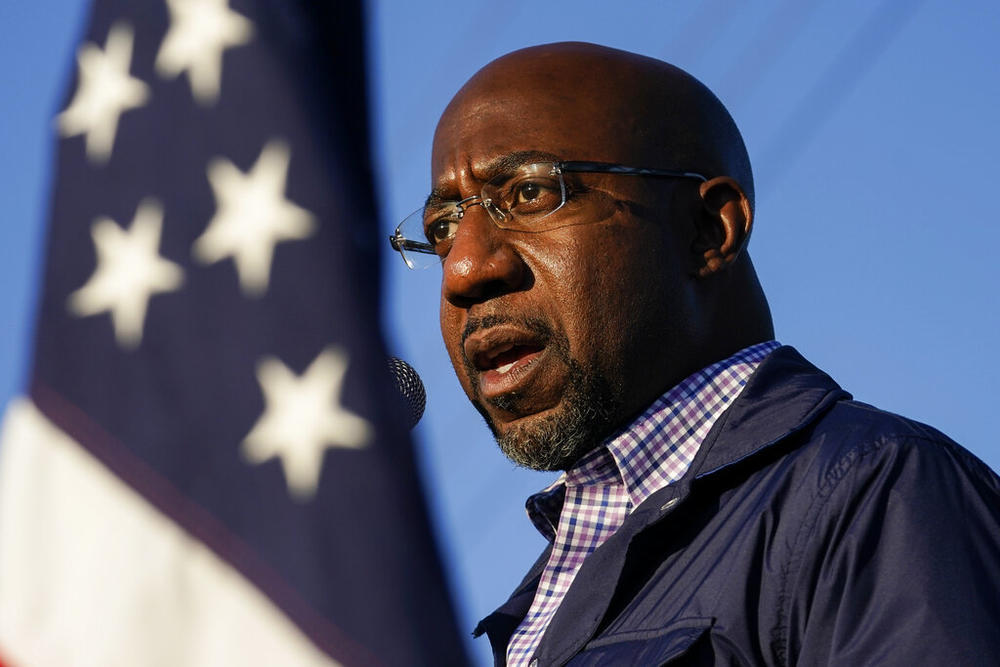

A supporter of the far-right Proud Boys group pleaded guilty this summer to threatening to kill Sen. Raphael Warnock, above, after his upset win over former Sen. Kelly Loeffler.

Credit: Brynn Anderson/AP Photo

A supporter of the far-right Proud Boys group pleaded guilty this summer to threatening to kill Sen. Raphael Warnock, above, after his upset win over former Sen. Kelly Loeffler.

The recent spate of violent threats against elected officials has a state oversight panel rethinking its position on whether home security systems should qualify as a legitimate campaign-related expense.

Just seven years ago, the state ethics commission ruled candidates and officeholders could not use campaign funds to help secure their homes. But after a tumultuous last year, the current commissioners are on the verge of reversing course.

The request comes from the Democratic Party of Georgia, but the escalation in threats toward public officials is a problem for both parties. There are prominent examples on both sides of the aisle, with both Democratic U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock and Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger the target of death threats in the wake of the 2020 election.

“It is important to note that particular vitriol has been directed towards candidates and elected officials who are women and persons of color,” Matt Weiss, the attorney for the Democratic Party of Georgia, told commissioners Thursday.

“Sadly, in the current political environment, holding public office, being a candidate for state or local office, or even working for a candidate or an officeholder is likely to be accompanied by threats of death and bodily harm, such that purchasing, installing and maintaining a home security system is necessary for protection.”

There was broad consensus Thursday at the Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission meeting that the state’s political climate had, in fact, changed since just 2014 when the ban on using campaign funds for home security systems was adopted.

A supporter of the far-right Proud Boys group pleaded guilty this summer to threatening to kill Warnock after his upset win over former Sen. Kelly Loeffler. Warnock’s victory helped put the Senate chamber in Democratic hands.

Raffensperger and another top election official, Gabriel Sterling, were open about the threats election workers and the agency’s leaders received in the aftermath of the presidential election, which went through three tallies. President Joe Biden narrowly won Georgia, making him the first Democratic presidential candidate to carry the state in four decades.

State Sen. Elena Parent, an Atlanta Democrat, also said she received “a torrent of abuse, attacks & death threats” after questioning the validity of the Trump campaign’s attempts to overturn Georgia’s election results. “It’s time to ask ourselves, ‘Is this who we are? Is this who we want to be?” she said back in December.

The commission is still working out the details of what’s known in agency parlance as an advisory opinion, which guide staff and commissioners as they determine if candidates are staying within the bounds of campaign finance rules. A vote could happen at the commission’s next meeting in December.

At issue is how best to write the rule so that campaign funds can be used to pay for home security equipment and subscription fees without the system personally enriching a candidate or officeholder.

Joe Cusack, who is part of the Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission’s compliance team, noted that insurance companies reward homeowners who have home security systems with a lower rate.

“We’ve tried to thread that needle in this case, recognizing this is a different political atmosphere than when this question was presented about seven years ago,” Cusack said. “We recognize that there is some need for this, but we are very cognizant that campaign dollars do not need to be turned into personal assets.”

In that spirit, commissioners are considering letting an individual use campaign funds to rent the equipment until their candidacy or time in office ends. If the funds are used to buy equipment, the individual would have to sell the device and return the funds to their campaign account.

Cusack said the staff is trying to adhere to the Federal Election Commission’s rule on the national level. The Georgia commission rules apply to statewide and local candidates.

The commission increased the maximum amount of money a political donor can give to their candidate of choice, clearing the bar for beefier donations ahead of the 2022 election when the state’s highest offices will be on the ballot.

David Emadi, the commission’s executive secretary, said the increases were made to keep up with inflation. Several candidates have announced campaigns for offices up and down the ballot, but the politicking will not start in earnest until later.

“I think it’s more prudent to do so now before the campaign season really gets kicking in full swing so that everyone understands what the limits are for the duration of the 2022 cycle,” Emadi said.

The limit for races for governor and other statewide offices is now set at $7,600 for each primary and general election, up from $7,000, and $4,500 for a runoff, up from $4,100.

For local and legislative races, the new cap is set at $3,000 per primary and again for the general election, up from $2,800, and $1,600 for runoffs, which is up from $1,500.

The commission last bumped up the limit in 2019.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.