Caption

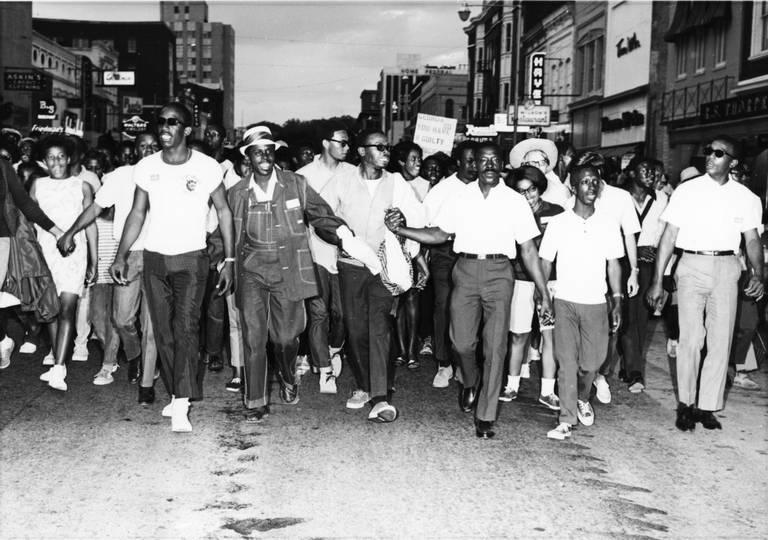

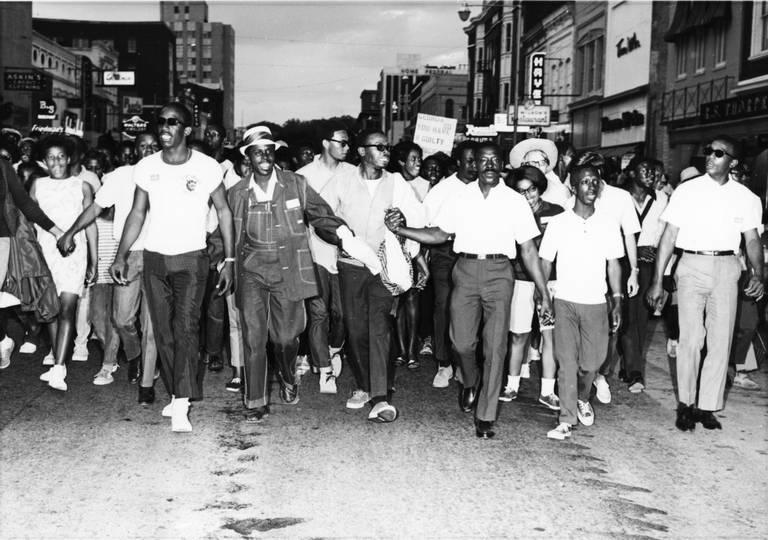

Civil rights marcher walk down Cherry Street in Macon in 1968.

Credit: Special to the Telegraph/Middle Georgia Archives/Washington Memorial Library

|Updated: February 4, 2021 11:23 AM

Civil rights marcher walk down Cherry Street in Macon in 1968.

When William C. Randall sat down in the “Whites Only” section of a Bibb Transit Co. bus in 1961, he was admittedly scared.

“We had seen on television how things have gone over in Alabama and some other places, and we were afraid that maybe the same thing would happen to us,” he said. “I was afraid, but I just put aside my fears, and we went on.”

Randall was one of 15 young people, most of whom were still in high school, who boarded buses on Feb. 25, 1961, in the first reported demonstration to desegregate the buses of the Bibb Transit Co., which was privately owned at the time.

Civil rights activists organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama five years earlier, and Randall, who was 17-years-old in 1961, said he was annoyed that there hadn’t been demonstrations in Bibb County.

His father, William P. Randall, was the head of the Youth Council for the NAACP, comprised of around 300 kids.

Randall told his father he wanted to organize a demonstration on the buses, and his father told him if he could find enough children to participate, he would help him.

“So, I thought it would be an easy thing out of 300 kids, but I was only able to get 15 and most of them were my relatives,” Randall said.

The organizers created five teams of three people to board buses at different bus stops, and they made sure that each group had a male to go with the females, Randall said.

They boarded the buses on that Saturday and sat in the “Whites Only” section.

“When we were asked to move, we refused to move. They pulled the buses to the curb, called the police, and we were all arrested,” he said.

A photo of The Telegraph article naming the 15 youths who participated in the first bus demonstration in Macon.

Shirley Randall Irvin said she always had faith that her uncle, Randall’s father, wouldn’t lead them down the wrong path. That’s why she stepped onto a bus on Feb. 25.

“We was apprehensive because you just don’t know how it going to end up, so I won’t say that we were cool as a cucumber,” she said. “But we had faith that everything was going to end up all right.”

After her father died when she was 6 years old, Irvin said her uncle became a father figure for her and her siblings.

William P. Randall was the type of person who wanted to help everyone, Irvin said, so she knew participating in the demonstration was the right thing to do.

“We felt that we needed to do it because it was time to do it,” she said.

Demonstrators under 16 were taken to the juvenile detention center, but 12 youths, two of whom were in their early 20s, were taken to the Bibb County Jail above the county courthouse .

The Telegraph reported the names and addresses of theindividuals who were taken to jail, a practice that has since been eliminated; however, it is unclear why not all of their ages were listed. The names of the three children taken to the juvenile detention center were not released.

Julia Lofton, 17

Barbara Johnson

Herschell Randall, 20

Annie Dell Randall, 19

Carl Brantley, 21

William Randall, 17

Harold B. Carswell, 18

Oressa Glover, 17

Cheryl Lickett, 17

Shirley Randall, 17

Harold Wilson

John E. Glover

Although they weren’t in jail long because his father had planned to bail them out, Randall said it was hot, and the officers removed the light bulbs from their cells. They sat in the dark for a couple of hours and sang freedom songs, such as “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Us Around,” Randall said.

“We kept singing… to keep our spirits up. It was hot up there,” Randall said. “Our fears had sort of gotten away from us. They had sort of gone then... We were singing, and we were in pretty good spirits.”

When they were bailed out of jail, Randall said a restaurant owner had prepared them a spaghetti dinner, and they were praised when they walked into school on Monday.

“We were greeted by the students as conquering heroes and most of the teachers,” Randall said with a smile. “They lauded us for our courage.”

After that first demonstration, Randall participated in the Civil Rights Movement in multiple ways. He participated in protests in Baltimore while he attended Morgan State College, and he believes he’s the only person living in Bibb County who participated in the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery marches, he said.

He practiced law for 29 years, served in the General Assembly for 24 years and retired as the chief judge of the Civil and Magistrate Court of Bibb County after 20 years of service.

After the first demonstration Randall said more followed.

The next demonstration started nearly a year later when four Black ministers boarded a Bibb Transit Co. bus in Macon on Friday, Feb. 9, 1962.

Randall said his father called the attorney for the bus company, on Saturday and requested to meet with him on Sunday to negotiate their terms.

From left, William P. Randall, Ralph David Abernathy, Martin Luther King and an unidentified man during King’s visit to Macon on March 23, 1968, to speak at New Zion Baptist Church.

The attorney refused to meet with the senior Randall on Sunday because he went to church on Sunday, Randall said.

“My daddy said, ‘Well I go to church, but this is important,’” he said.

William P. Randall told the attorney they were planning a boycott of the buses to start on Monday, so if they didn’t speak on Sunday, it would be too late.

“Let ‘em rip,” was the attorney’s response , Randall said.

The boycott started Monday with the goal of desegregating the buses and having the bus company hire Black bus drivers, and it lasted three weeks.

The boycott ended with a ruling from Federal Judge W. A. Bootle ordering the desegregation of Bibb Transit Co. buses.

“After that, the city administration decided it was better to negotiate things rather than going through demonstrations,” Randall said.

Although Maconites held multiple demonstrations to desegregate businesses and other aspects of life in Macon, many city institutions were integrated without demonstrations or lawsuits, including Washington Memorial Library and Bowden Golf Course, Randall said.

“We just did things relatively smooth here in Macon and Bibb County, and it was because of the white leadership working with the Black leadership to bring about what was going to be inevitable. It was going to happen, so let’s do it in the best way possible,” he said.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with the Macon Telegraph.