Caption

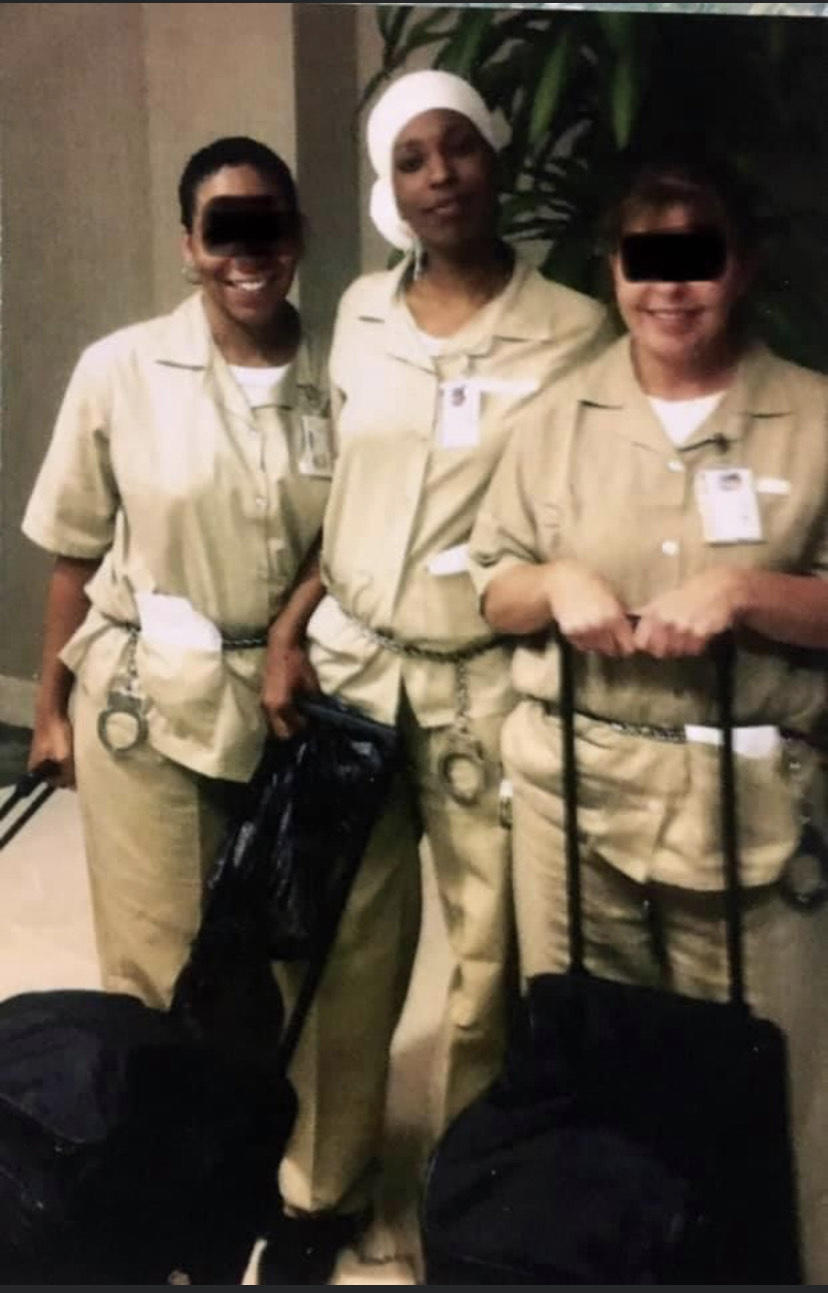

Kareemah Hanifa, left, stands with a patron at her Marietta hair salon in 2019. In addition to running her business, Hanifa advocates for others like herself who, long after serving their sentences, still shoulder the burden of their criminal histories.

Credit: Courtesy of Kareemah Hanifa