Section Branding

Header Content

These Artists Will Change Your Mind About Winter

Primary Content

I hate snow. Which means I most especially hate this week of the year. The week winter begins. It means snow could come. Or, G*d help us, snow is already here. I know, bah humbug. Still ...

I did like it once. Laughed my way through an 8-foot snowstorm years ago in Boston. But I was young. Now ... not so much. Although every time I look at this painting, it takes me back to those happy Boston snow days.

Frederick Childe Hassam (he never used the Frederick; a friend told him Childe was "more exotic") was born in Boston and early on began painting cityscapes. At Dusk (Boston Common at Twilight) was his first. I visit the picture every time I'm at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and a postcard of it is taped up next to my bed. It exactly captures how I felt in the three winters I spent there. Cold. A little melancholy at sundown. But mostly content, loving the crisp air, the charming old buildings, the smell of the park. And the pink twilight.

Museum of Fine Arts curator Erica Hirshler says in 1885, Hassam was painting modern Boston — new buildings lining the left side of the street, electric street lamps (not gas). "And the fact that the woman is walking unchaperoned in the city reflects a different way that women interacted in an urban environment." She and the little girls all carry muffs to keep their hands warm. Except for the muffs and a few other details, the place looks just the same today.

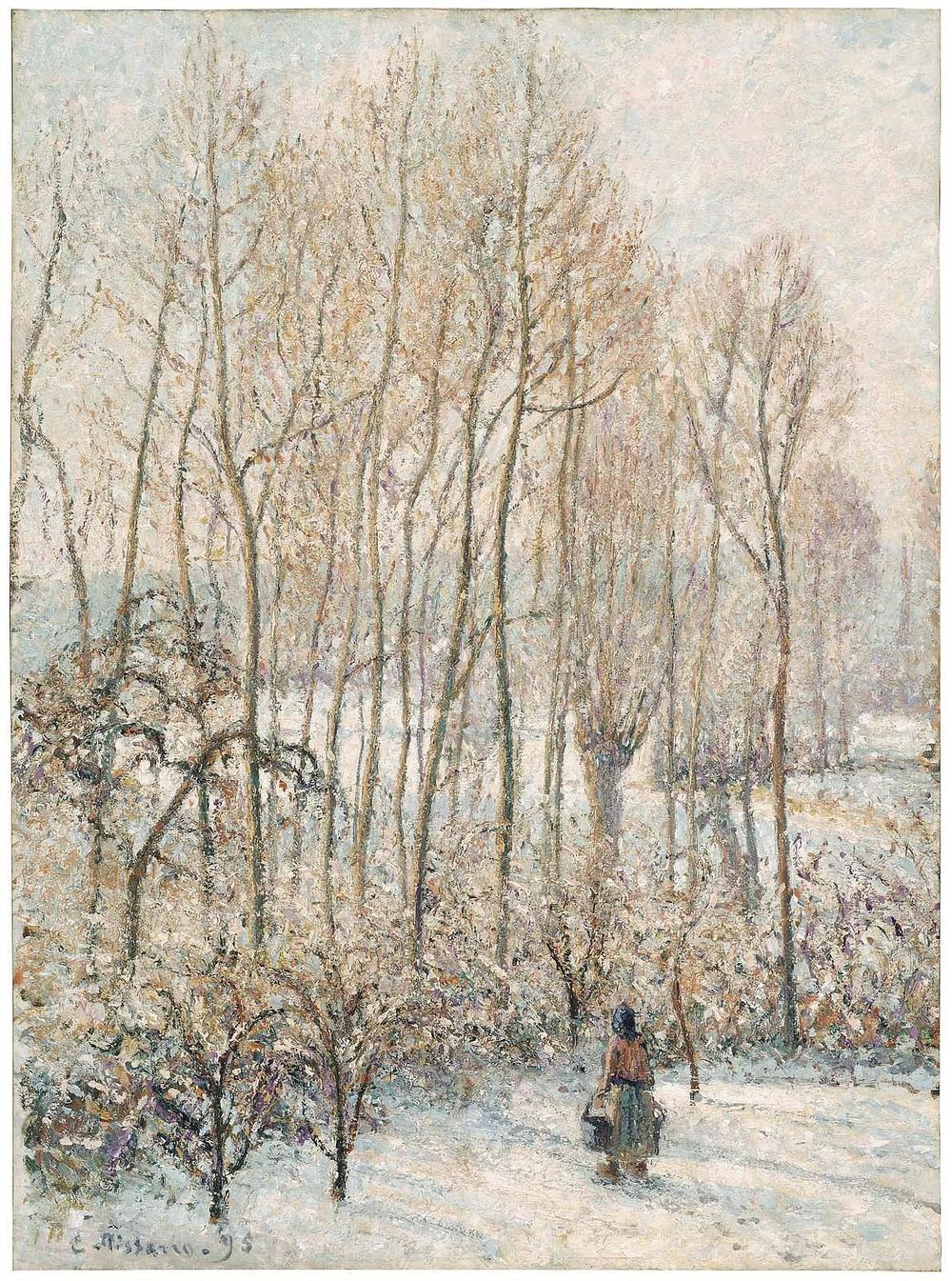

Hassam was an American impressionist. Camille Pissarro was a Danish French one who influenced Paul Gauguin and painted with Paul Cézanne. His gorgeous snowy scene looks like iced lace.

Pissarro's snow barely has any white in it. If you look closely, you'll see blues, pinks, yellows. Curator Hirshler points out, "Each separate color remains distinct but blends to say 'snow.' "

All these pictures are in the MFA's collection (the museum just closed again — pandemic). They know their snow in Boston. And they introduced me to a Norwegian artist who not only knew snow but had some truly original perspectives on it.

Look how that snowy hill just spills toward us. It takes up three-quarters of the painting. Frits Thaulow puts the horizon line almost at the top of his canvas. Very modern. You don't see much of anything but the snow and its shadows (and again, so many colors in this snow — the shadow is almost lavender). This fellow Thaulow makes a world in his snow. There weren't any ski lifts in the 19th century. That's why he paints those footprints, going up the hill.

Thaulow had some very nice connections. Gauguin was his brother-in-law, Edvard Munch his cousin, Claude Monet a good friend. He got Monet to go to Norway so they could paint snowy scenes together. Thaulow also used pastels. A really difficult medium: You can't correct something in pastel the way you can in oil paint — can't just scrape it off. Pastel smudges, is fragile, but stays where it's put for the long haul. An artist has to know that he/she is doing to use it well. Thaulow knew.

"Pastel is really colored dust," Hirshler says. "This scene of snow blowing off the roof in a storm is a perfect synthesis of subject and medium. The snow looks like powder. So does pastel. You can see how good he was to make that very light white drift across the barn's red side," she goes on. "You can feel the wind. It feels cold."

For me, the perfect way to experience snow is to see it hanging on the wall of a great museum! Hirshler would agree, but she has New England in her blood so she enjoys cold and snow, "when I have dry feet." She cherishes memories of trudging through deep snows in sunshine under deep blue skies. "It's just like walking through diamonds."

Time to warm up.

A member of Mary Cassatt's family gave the museum this tea service. Cassatt painted or drew it more than once. Its most intriguing appearance is this one:

Cozy little scene, no? No. Odd, in some ways. "The tea service is almost a third character in the painting," says curator Hirshler. "It's almost as big as the two women." And what about the women? The hat-and-glove one is visiting (love the raised pinkie!). She's looking away from her hostess — uneasy? Something unpleasant came up? Sipping tea (so her face is covered). Maybe Cassatt had trouble with lips? Remember John Singer Sargent, "A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth"? And the hostess also looks away — thinking? Bored? "Makes you wonder if their relationship is cooler than the tea," says Hirshler.

Tea's over. Once more into the real winter breach. To prepare ourselves, it will help to take a look at this video. The bravest (or most foolhardiest) activity you'll see in a really long time.

Eat your hearts out, Florida. Happy winter, everyone!

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing offerings at museums closed because of COVID-19 or at museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.