Section Branding

Header Content

PAC That Sent Controversial Help To D.A. Campaign Fails To Meet Disclosure Deadlines

Primary Content

Back in September, when election fever was running high in Savannah, angry conversations erupted around town about outside money trying to sway the race for district attorney.

Local Facebook groups with conservative leanings, Republican Party stalwarts and self-described patriot organizations were outraged over the Justice & Public Safety PAC, a Washington, D.C.-based political action committee with a track record of supporting progressive politicians. In the Democratic primary, the group had supported Shalena Cook Jones, a former assistant district attorney challenging incumbent Meg Daly Heap.

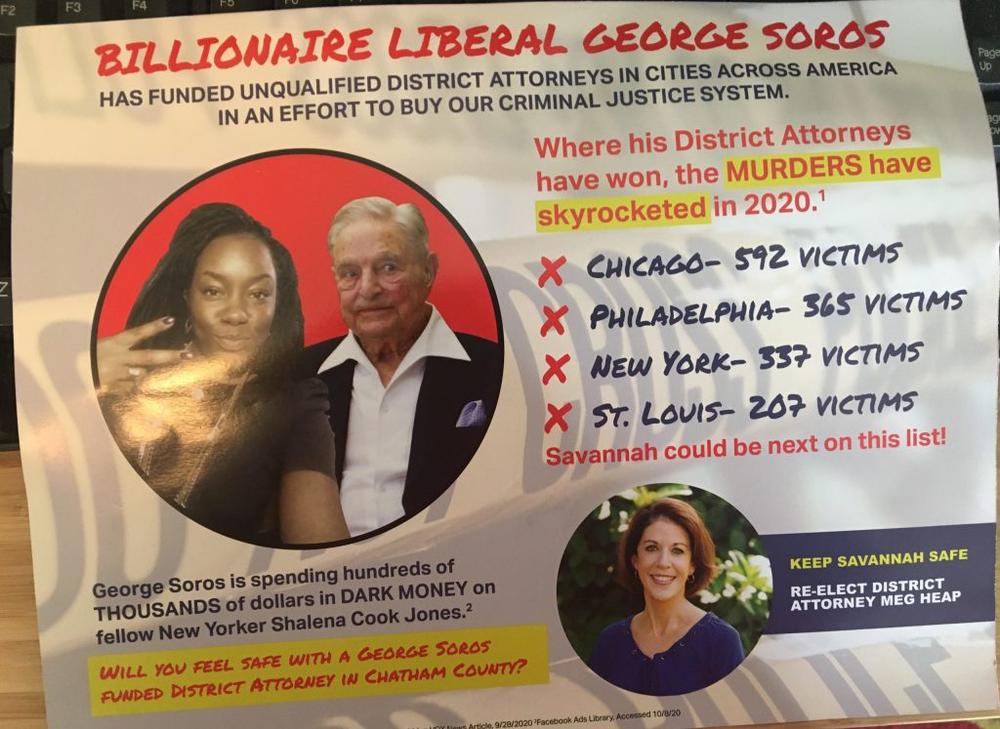

Then, a new out-of-state political action committee began blanketing mostly affluent white neighborhoods in greater Savannah with campaign literature. Voters from both parties expressed disgust over those ads paid for by Protect Our Police PAC in support of Heap for using messages deemed as racist and anti-Semitic.

A month after the election, the results are clear: Political neophyte Jones defeated Heap. What’s still unknown, however, is how much money the pro-police organization spent in Coastal Georgia trying to prevent that.

State Oversight Weak For Outside Campaign Money

American politics are awash with money and the pro-police PAC represents only a drop in that ocean, especially considering quarter of a billion dollars being spent for January’s Senate runoff election. Yet the work of the Philadelphia-based group provides a cautionary tale about how organizations with deep pockets or deeply held beliefs are shielded from public scrutiny during election season due to the weakness of Georgia’s laws governing the source of campaign materials and money seeking to influence voters.

While Georgia requires candidates and independent political action committees to file routine expenditure reports through an election cycle, enforcement of those rules lags so far behind events as to be meaningless when it comes to helping voters understand who or what group is trying to shape their views.

Protect Our Police registered with the Georgia Ethics Commission, the agency that oversees election campaign spending, on Oct. 2. According to state law, it was required to file campaign expenditure reports to the Georgia Ethics Commission by Oct. 20, two weeks before Election Day.

As of Dec. 4, though, that information was still missing.

In contrast, Justice & Public Safety PAC, as well as the Heap and Jones campaigns, filed expenditure reports according to state requirements. As of Oct. 26, Heap had raised $226,960 for her race and had spent close to $192,000. Jones’ campaign filing on Nov. 3 showed she had raised $50,415 and spent just under $40,000. Justice & Public Safety spent $181,259 to support Jones in the primary and fall election, according to disclosures filed Oct. 27.

Protect Our Police PAC did not respond to repeated email or phone requests for comments about the group’s campaign expenditures in the Chatham County race, or an explanation for why it had failed to abide by the state’s October deadline for expense filing.

Campaign finance reform experts say that the fines for violating disclosure laws in Georgia are so paltry as to make them negligible in races where hundreds of thousands of dollars are committed for a candidate or issue.

The Georgia Ethics Commission, which oversees election campaigns, assesses a minimum $125 penalty for late campaign finance disclosure forms, fines that could potentially increase up to $1,375 depending on the seriousness of the violation.

The nonpartisan Center for Public Integrity gave Georgia a failing grade in campaign finance oversight, as part of a 50-state investigation in 2015 that assessed government and systems meant to deter corruption. “There’s not enough oversight and accountability built into the operation of Georgia’s state government, which led to some unethical behavior and a high risk of corruption,” the group’s report said.

The Ethics Commission says it “actively investigates” violations of the Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Act when said violations are discovered through internal audits performed by Commission staff or through verified complaints filed by members of the public.

PAC Set Up To Promote Police In Turbulent Time

POP was founded over the summer by retired Pennsylvania law enforcement officers worried that crime rates were growing and that police around the nation were losing the respect of Americans. The founders, who have no known ties to Georgia, publicly endorsed Heap in a press release dated Sept. 22 in which the group promised to spend this fall upwards of $250,000 for 40 candidates that it was supporting in elections across 15 states.

An investigation by The Current of the group’s campaign expenditure records in other states show that Georgia is one of only three states where it has not filed any details of its campaign work. Publicly available disclosures reviewed by The Current in the 15 states where POP endorsed candidates show that the PAC spent at least $191,550 on its endorsed candidates in 12 states.

The Current could find no campaign finance filings by the group in Georgia, Nevada and Wyoming. These other two states received a failing grade from the Center for Public Integrity’s report as well.

Protect Our Police sprouted up over the summer as part of a movement to support law and order in response to civil protests that had spread across the county in response to police killings of Black Americans.

“Law abiding citizens have no reason to be afraid of police,” one of its founders, Nick Gerace, told Fox News in July. “But when criminals are not afraid of the police or not afraid to go to jail, then we have a problem. Wherever you have rogue mayors or DAs who are radicals, you are going to have these issues. That is why we started Protect Our Police PAC. We are trying to find candidates who are going to back the Blue always.”

In a separate interview to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Gerace described the group’s motivation as “a counter-punch to George Soros,” the billionaire investor who is the main donor for Justice & Safety PAC. Soros, an outspoken proponent of progressive causes such as revoking the death penalty and judicial reform, is often a target of conspiracy theorists who paint him as part of an alleged Jewish cabal of financiers secretly influencing world events. The allegation is a key tenet in anti-Semitic propaganda that underpins Nazi and extremist propaganda.

PAC's Bring Uncontrollable Messages, Money

It’s unclear the exact reason why the police PAC selected Heap as among the 80 politicians it had considered endorsing from around the country.

Heap’s campaign told The Current that she did not seek the PAC’s endorsement and said that the group had been made aware of her race against Jones by another Georgia district attorney.

When Jones won the June Democratic Party primary to challenge Heap, she had no prior political experience. But she did have support from Justice & Public Safety. Campaign expenditure reports filed on June 23 showed that the group had committed $101,950 to her primary victory.

Few people in Coastal Georgia were aware of the Soros-backed organization before this fall. In Philadelphia, however, his PAC has greater name recognition since a bitterly contested 2017 race for district attorney there.

Justice & Safety poured more than $1 million into the campaign supporting civil rights lawyer Larry Krasner. Krasner, a former prosecutor who opposes the death penalty, was dubbed soft on crime by several conservative commentators such as Gerace.

In Savannah, Heap’s campaign messaging took on a strident law and order tone as her campaign against Jones grew tighter, more closely matching talking points of the PAC and national Republican organizations.

At an October campaign event, Heap said she was “concerned” about a Jones victory. She emphasized a quote from her challenger in which Jones allegedly encouraged Black Lives Matters protesters to “riot and burn.” “I know that if she gets in, my good prosecutors are not going to stay, and you’re not going to have people who can prosecute murders,” Heap told a room of mainly white supporters.

Then, direct mailers from Protect Our Police started landing in residential mailboxes in affluent neighborhoods like Isle of Hope and Coffee Bluff. A billboard off of Route 17 near Richmond Hill went up depicting Jones in a pose that resembled those popularized by so-called gangster rappers. Jones, a Black University of Georgia law school graduate married to a military veteran, was horrified by the ad. “The image was intended to be racist,” she said.

At least one such piece of PAC campaign literature showed a shadow figure that appeared to be a likeness of Soros next to a picture of Jones who was posing with her arms crossed and fingers in a “V” sign. The image, as well as a separate YouTube ad created by the Heap campaign also featuring Soros as a boogeyman figure, sparked a strong backlash across Savannah’s Jewish community, leading to at least one meeting between leaders of Congregation Mickve Israel and Heap.

Heap’s campaign issued a public apology. But she also explained that she was not responsible for the PAC’s campaign tactics, citing the law which forbids interaction between independent political action committees and political candidates.

When asked to comment about the PAC’s failure to report its campaign finance expenditures in Georgia, Heap’s campaign spokesman cited the same law.

The 40 candidates endorsed by Protect Our Police this fall competed in a variety of elected positions: state legislators, state attorney general, city council or county commission. A review by The Current shows that among that group, 23 candidates lost their races on Nov. 3, while 18 won.

In Georgia, political action committees and candidates face a Dec. 31 deadline to file final campaign expenditure reports.

Reporter Laura Corley contributed to this report.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, a non-profit newsroom providing in-depth journalism for Coastal Georgia.