Section Branding

Header Content

A National Fight Over Who Is Counted In Voting Districts May Arise From Missouri

Primary Content

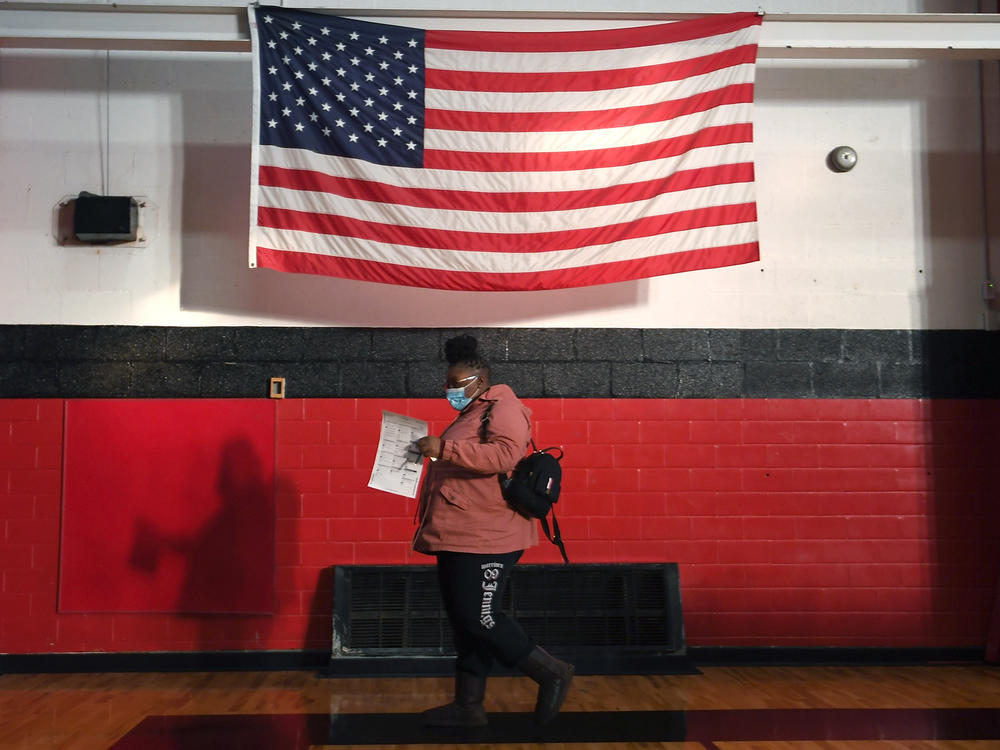

Voters in Missouri approved amending their state constitution this week with a subtle change that could spark a national legal fight over who is counted in voting districts.

In general, political mapmakers around the country have long drawn state legislative districts once a decade based on the total number of people living in an area as determined by the latest census results.

With the support of more than 51% of those who voted on the ballot measure, Republican state lawmakers have changed redistricting requirements so that going forward districts have to "be drawn on the basis of one person, one vote," according to the newly-passed Amendment 3.

It's not clear exactly how the phrase "one person, one vote" will be interpreted when the state's voting maps are expected to be redrawn next year by either bipartisan commissions or judges from Missouri's appellate courts. There is no requirement under Amendment 3 for Missouri to stop redistricting based on total population.

But Missouri Solicitor General D. John Sauer was explicit about the state government's interpretation during a court hearing in August.

"So 'one person, one vote,' the criteria is based on the number of actual eligible voters in a relevant district as opposed to an absolute population," Sauer told state appeals court Judge Alok Ahuja during a hearing for a lawsuit over how the amendment was presented on election ballots, which did not go into any detail about how the redistricting criteria would be modified.

Sauer's comment echoed the interpretation of Republican state Sen. Dan Hegeman of Cosby, Mo., a lead sponsor of the legislation that proposed the constitutional amendment who said during a Missouri senate floor debate in January that the phrase meant using a count of "people that are able to vote."

Drawing state legislative districts based on the number of U.S. citizens old enough to vote would be a radical shift in political mapmaking. A GOP strategist concluded it "would be advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites."

Opponents of Missouri's Amendment 3 say the new criteria open the door to redistricting that does not take into account the political representation of children, noncitizens and other residents who are not eligible to vote.

According to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice, redistricting based on the numbers of adult citizens could siphon away political representation from two major metropolitan areas in Missouri — greater Kansas City and the suburbs of St. Louis.

The change could also come with "stark" racial disparities, the Brennan Center report says, potentially leaving out more than half of Asian and Latino residents in Missouri and more than a quarter of Black residents while excluding only 21% of the state's white population.

Still, it remains an open question whether it is legal to draw voting districts based on the number of eligible voters or another group other than all residents. The U.S. Supreme Court left it unresolved in its 2016 ruling for the Texas redistricting case Evenwel v. Abbott.

"That open question could be one of the big fights of this decade," Michael Li, a redistricting expert who is a senior counsel for the Brennan Center's Democracy Program, told NPR in May.

As the 2021 redistricting season draws closer, the ingredients for a potential Supreme Court fight are lining up.

Political mapmakers need block-level data about people's U.S. citizenship status in order to carry out redistricting based on eligible voters — and the Census Bureau says it is planning to release that information next year, although the exact timing for it and other redistricting data from the 2020 census is unclear due to delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic and last-minute schedule changes by the Trump administration.

After the Supreme Court blocked the administration last year from adding a citizenship question to 2020 census forms, Trump officials pushed ahead with using an alternative source to produce block-level citizenship data — government records including Social Security Administration files, U.S. passport data and some states' driver's license information.

The administration has also directed the Census Bureau to try to use records to produce a count of unauthorized immigrants living in the country, which President Trump would need to attempt to make an unprecedented change to who is counted in numbers used to redraw congressional districts.

Despite the U.S. Constitution's requirement to include the "whole number of persons in each state," Trump wants to exclude unauthorized immigrants from the congressional apportionment counts.

Two lower courts have found the memo Trump issued calling for that change to be unlawful, and one of the courts declared it to be unconstitutional. The Supreme Court is set to issue its ruling after hearing oral arguments on Nov. 30.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.