Section Branding

Header Content

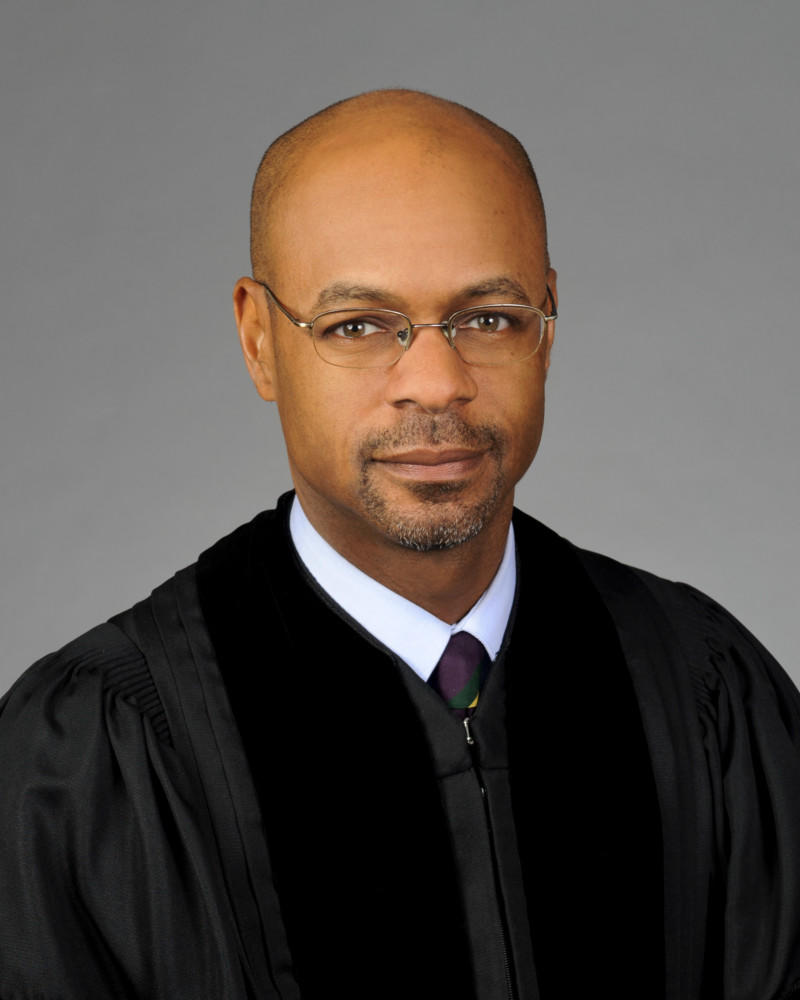

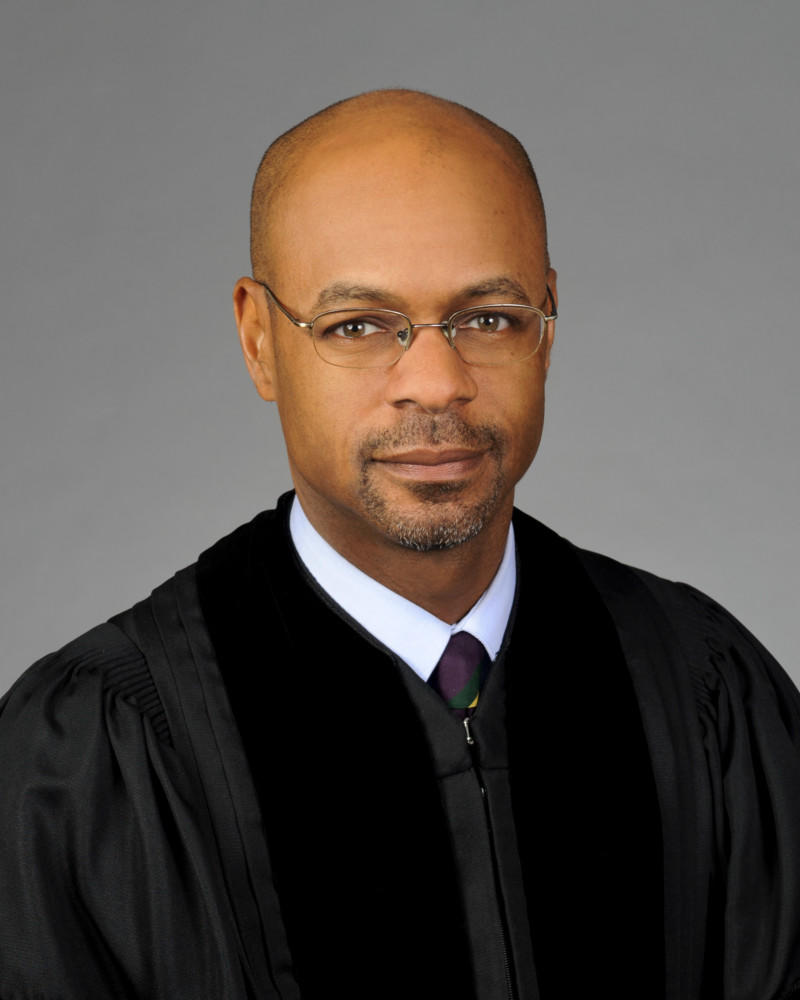

Ga. Supreme Court Chief Justice: ‘There’s This Pent-Up Frustration That’s Now Exploding’

Primary Content

With calls for social justice sweeping the nation, the chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court on Thursday said he understands the frustrations expressed by so many because for too long in the nation’s history the “law has not always been on the side of African Americans.”

“In fact, it worked against us intentionally,” said Chief Justice Harold Melton, who is Black. “I think it’s incumbent upon us as government officials, not just in Georgia but elsewhere, to not just give assurances that the wheels of justice will, in fact, move in a timely fashion, but to actually do it. We have to rebuild credibility with our communities. That trust has been broken.”

He added, “It’s important that when we see bad actors of any walk of life, we don’t wait to be urged to do the right thing – and we have to do it in a timely manner. Timely means, not too fast, but also not too slow. There’s a sweet spot there.”

Melton made his comments during a Zoom webinar hosted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, a free-market think-tank organization.

The remarks came on the heels of the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man who was shot seven times in the back by police in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The shooting resulted in professional sports leagues postponing games on Wednesday as basketball, baseball and soccer players joined in unison to protest the shooting caught on video.

It follows a string of fatal police shootings, from George Floyd in Minnesota to Rayshard Brooks here in Georgia, that have sparked protests and calls for social justice in cities around the country.

Melton’s court is currently considering a case at the heart of what is playing out in the street protests – a case involving the killing of a mentally ill Black man who was stunned to death by Washington County sheriff deputies.

Melton was prohibited from discussing the case, but he spoke freely about what it is like to be Black in America, what he has observed over the years and the importance of a fair judicial process.

RELATED: Case Involving Officers Who Tased Mentally Ill Man To Death Goes To Georgia Supreme Court

“There were always stories about law enforcement behaving badly, but it was so hard for the general population to believe that law enforcement -- that we know and love -- could conceivably behave badly,” he said.

Melton, who was appointed to the state Supreme Court in 2005 by then-Republican Gov. Sonny Perdue, said many believed the 1991 video-taped beating of Rodney King provided the evidence Black people needed to show the unfair treatment at the hands of police – that “clearly this can no longer be a debate.”

“Since that time, it’s been happening over and over again,” Melton said. “Sometimes, they were justified. Sometimes, they were not justified. Sometimes, it was close. But the overall perception was that there was not this insistence of holding law enforcement, when they do behave badly, to the rule of law.”

However, Melton cautioned against a rush to judgment.

“The beauty of our justice system is that it is a thoughtful process,” he said, “but we are definitely in the trust-building mode right now.”

Of the recent protests, he said, “There’s this pent-up frustration that’s now exploding that scares me from this standpoint, but is also healthy.”

“It’s healthy in that it’s another area where we as a society need to make sure that the rule of law is applicable. The desire is not just to have the rule of law applicable; the desire is not to have individuals shot unnecessarily,” he said. “But where that does happen, you want the rule of law to apply. That’s the healthy part.

“What scares me is because of the frustration that’s out there, I don’t know how discerning we will be as a community or as a society to be selective about when we express great outrage and where we say, ‘That was unfortunate, but that was within the bounds of the law,’” Melton said. “My concern is that we just won’t be as discriminating as we need to be, because police officers do have the need from time to time to use deadly force.”

He added: “We don’t need to over-correct – and in most things in society and in life, we tend to over-correct. If we over-correct in this area, it can be very, very dangerous.”

Here were other highlights from his speech, which has been edited for length and clarity.

On Being Chief Justice:

“I love being the person who makes the decision, as opposed to being a lawyer arguing on behalf of a client for a court to make a decision. ... There is a weight of responsibility that is heavy, and you want to get it right. You realize that everything you do impacts lives.”

On Systemic Changes:

“I always challenge people to tell me what in the world you’re talking about when they talk about systemic change. What is the system that you’re identifying and what is the change you want to see? So, if you tell me the system you’re identifying is the criminal justice system, then my next question is define to me what you mean by the criminal justice system and tell me which parts of that system do you think need to be changed.

“I do find when you’re able to define what that system is and you can identify what pieces need to be changed, meaningful – very meaningful – results can be found. We’ve seen the criminal justice reform that has happened in Georgia over the last several years, that’s a result of really putting fingers on aspects of the system that can be modified effectively. And that’s been great. …

“We tend to look at disparities in numbers involved in the criminal justice system as an indication that the criminal justice system itself is in need of even more reform. The challenge I have with that is those disparities that exist in the criminal justice system don’t just exist in the criminal justice system.

“If you look at the numbers in high school dropout rates, in teenage pregnancy rates, in domestic violence, in DFCS calls, in infant mortality rates, if you look at COVID, you see similar numbers across the board. The fact that we see those numbers in our criminal justice system doesn’t mean our criminal justice system is out of whack if they’re consistent with all the other demographics that we see. What it points to, to me, is a breakdown in communities, a brokenness in communities, a desperate need for healing in communities.

"Yes, that brokenness absolutely is a result of a lot of bad stuff that has happened – a lot of that attributed to racism.

“That’s the healing that needs to happen.”

On Disparities:

“For example, we know of the disparities that have happened in the criminal justice system. We also know that in the midst of COVID, many more children are going to have to learn at home. If we know what I just talked about, that we have systematic problems within our communities – our brokenness within our communities – those who are living in that brokenness don’t really have a good shot of effectively getting the support they need to learn at home.”

“That educational gap will broaden. So, if we’re concerned about our criminal justice system, we need to get involved on the front end to make sure that gap doesn’t get too broad – even broader – to see if we can narrow that gap. Because this is a real desperate time for those children who are at home and don’t have the support that they need, for whatever reason, to get the education that they need. If that’s not effectively dealt with, that gap is going to get worse and we’re going to see the impact of that in our criminal justice system down the road and in the other statistics that I just mentioned.”

On Georgia’s Criminal Justice Reform:

“Within the Black community, we have had a 25% decrease in the incarceration rate of African Americans within the last eight years. That’s huge. There has been no single, greater factor for advancement in criminal justice reform that deals with the issues that we are concerned about in a way that even comes close to that. It’s cost effective. It’s cheaper than putting a person in a hard prison bed. The reality is, when you go into a hard prison facility, if it’s for something that’s not for life, you’re coming back out within 5, 10, 15 years and, under the old way of doing business, we weren’t sending people back into society any better as a result of their experience. They were coming back harder, maybe angrier. This is just a smarter approach. … It’s reduced our recidivism rate by, I think, a third.”