Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Senate Proposes Comprehensive Dyslexia Bill

Primary Content

The state Senate is considering a bill that provides for dyslexia screening and additional resources for students with language-based disabilities.

Senate Bill 48 has received bipartisan support from state lawmakers, who want to implement dyslexia testing in pre-K through 2nd grade along with remediation opportunities.

What is Dyslexia?

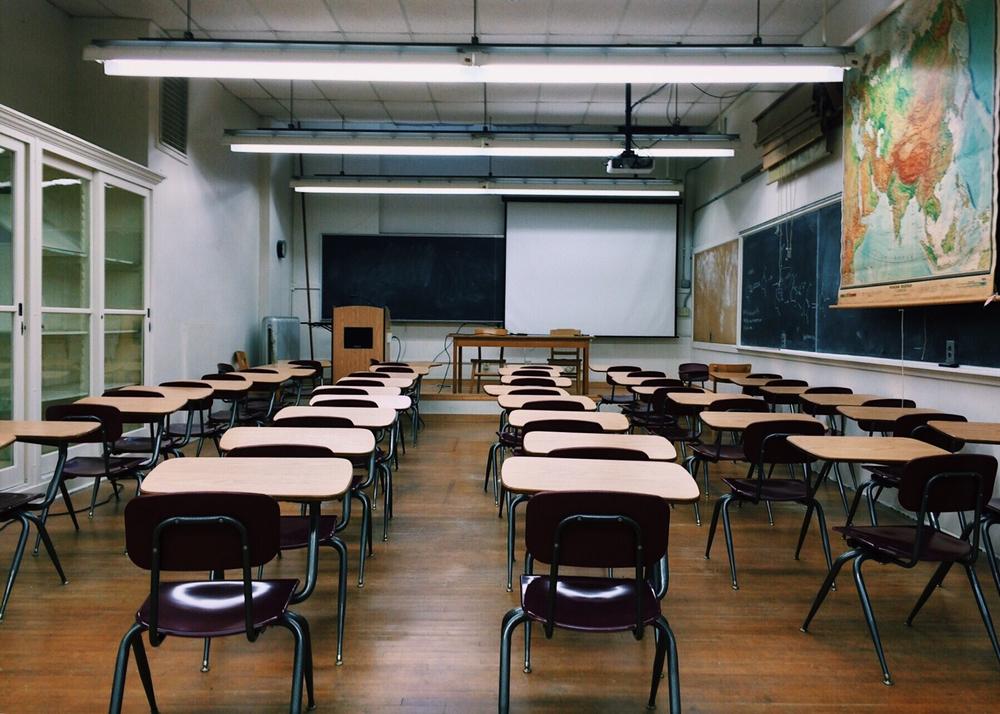

Dyslexia, a learning disability that makes it difficult for an individual to read and write, affects roughly 20 percent of the population and makes it difficult to succeed in a traditional classroom setting.

This means that of the over 1.7 million public school students in the state, roughly 350,000 are likely to have some form of dyslexia. For many families, the disability goes unnoticed and undiagnosed. For those that are able to recognize the signs, special tutoring and specialized private schools may help. But there is no statewide program that provides assistance for dyslexic students.

WATCH: Lessons from dyslexic students reshape literacy education

According to the proposed bill, “dyslexia is characterized by difficulties with accurate or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities… secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

The bill also notes that dyslexia is “often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities,” meaning that intelligent students are affected by this language-based disability.

Dyslexia is often related to genetics. If a parent is dyslexic, their child is more likely to be as well.

Early Intervention is Key

Natalie Felix, a Learning Specialist at the Swift School and an Orton-Gillingham Fellow-in-Training, says that by screening children for dyslexia and intervening at an early age, the state will save money in special education services.

“It has huge financial repercussions for schools and states and at the end of the day, students don’t have to fail. They don’t have to feel like they’re stupid,” says Felix.

According to a 2004 study by E.G. Willcutt and R. Gaffney-Brown, 20 percent of children with dyslexia suffer from depression and another 20 percent suffer from an anxiety disorder, likely as a result of low self-esteem after years of failure in the classroom.

“A lot of times the behavior that the kids express in the classroom—the anger, the frustration, pushing chairs, making a distraction—they’ll do anything to get away and escape from the work,” says Dr. Kelly Rush, Assistant Principal of Instruction at Matt Arthur Elementary School, a public school in Kathleen, Georgia. “It’s because they can’t do it and they can’t keep up with their peers.”

Felix says she’s also heard dyslexia called the “pipeline to prison.” She says that because we live in a society that is highly dependent on literacy, it is difficult for these students that can’t read and write to succeed and provide for themselves.

What’s the Solution?

Felix says that early identification and remediation are essential. They both support the bill’s method of doing so.

“There are huge ramifications, as far as effectiveness of intervention,” says Felix. “So when you intervene early, remediation is a lot easier than waiting until 4th or 5th grade… it takes three or four times as long to remediate an older student than it does a younger student.”

There is no cure to dyslexia, but there are certain techniques, like the Orton-Gillingham Approach, that can help dyslexics better comprehend reading and writing and succeed in school.

What Would the Bill Do?

The bill would also require the Georgia Department of Education to create a dyslexia informational guide for parents and each board of education to provide additional learning opportunities for dyslexic students within their county. Under the law, supplementary training would also be required for teachers to better educate dyslexics.

Felix, who attended and spoke at informational committee meetings prior to the bill’s proposal, says that the screening and intervention elements are the most important components.

The screening process will help educators identify “red flags” in young students. These red flags include a lack of phonological awareness, slow sight word reading and impaired automatic naming abilities.

While schools like the Swift school are specialized for dyslexic students, not every child with dyslexia can afford their services.

“The biggest thing about this bill is that… students across all economic levels can have access to identification and intervention. That’s the power of this bill,” says Felix.

To even be formally diagnosed as dyslexic, a student must go to a private psychologist.

Currently, Georgia is one of few states with no dyslexia laws on the books. While federal law lists dyslexia as a type of learning disability, it merely cites it as an example and does not define it nor provide for remediation.

“There’s no test that our psychologists are going to give that would say ‘your child is dyslexic.’ That doesn’t happen in the school systems in Georgia right now,” says Dr. Rush.

The bill also defines and recognizes other language-based disabilities, like aphasia, dyscalculia and dysgraphia. If passed, it would roll out in three public school systems before expanding to the entire state.

During last year’s session, the House passed a resolution that encouraged schools to recognize dyslexia as an issue in public education, but this resolution did not take any tangible action.

The bill has been reported favorably by the Education and Youth Committee and will proceed to the Rules Committee to decide when it will be voted on, says Sen. P.K. Martin, a sponsor of the bill.