Section Branding

Header Content

Savannah Harbor Expansion Puts Fish, People At Odds

Primary Content

For years, the deepening of the harbor in Savannah has been one of the most eagerly awaited boosts to Georgia’s economy. With a deeper harbor comes more goods to move across the country.

But a deeper harbor will also make life harder for the endangered Atlantic Sturgeon and its smaller cousin, the Short-Nose Sturgeon.

To make up for that, there’s renewed attention to an old lock and dam on The Savannah River 18 miles downstream from Augusta, and a rocky spot on the river known as “The Augusta Shoals.”

The "Augusta shoals” are hard to reach. The water is shallow and the rocks just below the surface make navigation by boat dangerous. Dense trees and a sharp slope leading the water’s edge make it equally treacherous on foot. But the sturgeon have been swimming to this spot for millions of years. The shallow, fast-moving water and rocky river bottom make an ideal spawning ground for the bony-plated fish that can grow to 14 feet and 800 pounds during their 60-year lifespan.

Their access to this ideal spawning ground was interrupted in 1937 with the construction of The New Savannah Bluff Lock and Dam. That, combined with overfishing in the 1900s and late 1800s landed the fish on the list of endangered species.

Andy Herndon is a sturgeon expert with The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. He says the best way to bring back the fish from the brink of extinction is to get rid of The Lock and Dam. And, as part of the environmental remediation connected to the Savannah Harbor Expansion Project, he believes now is the time to do it. Deepening the harbor is destroying habitat for the fish, so, by removing the lock and dam and giving the fish access to their historic spawning grounds, the calculus is that the number of new sturgeon born in The Augusta Shoals will outpace the number the number of sturgeon that die as a result of the destruction of their habitat in the harbor.

The Army Corps of Engineers has plan. They want to knock down the dam and replace it with a rock weir. It’s kind of like a staircase with water running down it that fish can climb. But, unlike the dam, a weir won’t hold water upstream. A simulation of conditions with the rock weir replacing the lock and dam left boat docks resting on mud flats, old pilings exposed and a stifling stench of decomposing aquatic vegetation filling the air.

That’s a BIG problem if for riverfront property owners. A recent town hall meeting in The Augusta/Richmond County Commissions chambers digresses into a shouting match, with one resident proclaiming, “Damn those damn fish! Forget the fish! God put us humans at the top of the food chain for a reason. And there is no reason why we should put the fish above our needs.”

But, the federal government does care about the fish. Under the Endangered Species Act, the damage to sturgeon habitat at the Savannah Harbor project has to be made up for somewhere else. Most people who live along The Savannah River have never seen a sturgeon. And that, environmentalists would argue, is precisely why removing the lock and dam is so important.

People who bought property along the river, and got the permits necessary to build boat docks, knew what they were getting into, or so says Savannah River keeper Tonya Bonitatibus.

“The river is a public resource," Bonitatibus said. "And if you choose to live on the river, or any body of water, you are obligated to follow the laws of the community. The Army Corps of Engineers looks at home ownership in a slightly different way because the river is a public resource and that’s their first obligation.”

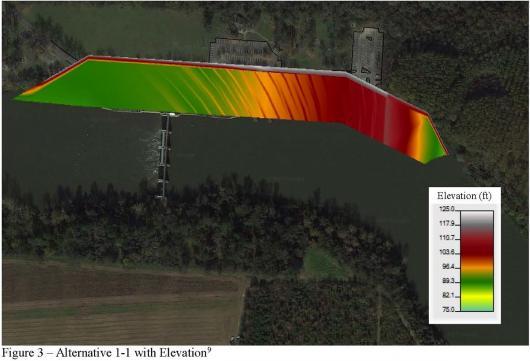

Still, the Army Corps of Engineers is trying to balance the needs of fish and people. They have other ideas besides the rock weir, one of which is known as “alternative 1-dash-1.” Army Corps of Engineers spokesperson Russell Wicke described it this way: “The lock and dam gates will remain, as will the inner lock wall. And the fish passage would go through where the current lock is now, but also extend a little bit into where the current park is now.”

It might keep water levels upstream closer to what homeowners want. But Wicke says any alternative has to work just as well for the sturgeon as the preferred plan, the rock weir, because the whole purpose of this is get the fish upstream of the lock and dam.

If Augusta residents really want a fish friendly version of the dam rather than the rock weir it will cost them. The Corps estimates “alternative 1-dash-1” will cost north of $300 million, which is more than twice as much as the rock weir. State and local taxpayers would have to cover the difference.

Although the public comment period for the project ended on April 16, The Army Corps of Engineers is months away from a final decision.

They are required by law to read and respond to each of the more than 400 comments submitted. Then, their district office in Atlanta will make the final decision. Whatever they decide will be made public no earlier than August.