Section Branding

Header Content

Camp Offers Support, Outlet For Kids' Grief

Primary Content

Schools are letting out around Georgia, and many kids are heading off to camp. There are camps for just about everything - from sports to music to the outdoors. But for children coping with a recent loss, bereavement camps can be a place to find healing and support.

In a sunny clearing between some pine trees, campers are running around in superhero capes. They seem to be having a lot of fun. But as nine-year-old Trina Franken explains, there’s more to Camp Aloha than that. Asked why she likes the camp, she says "that it’s letting you cry, and it’s really fun, and there’s pools, and it’s my first sleepover camp ever!"

Betsy Kammerud is a bereavement counselor and camp coordinator. She says people are often surprised to hear about the laughter and fun that’s part of a camp for grief. "I think that’s the key is that they get that opportunity to go and do normal kid stuff and to play and laugh and joke around," she says, "so that it’s not that full-on, all day, constant emotional push."

Kammerud says that’s also part of how kids operate: they might be crying one minute, but laughing and playing the next.

"People think, oh, the kids are fine, but really they’re still feeling that grief; it’s just coming out in a different way," she says.

Sixteen-year-old camper Kayla Tully says it’s easier to let her grief out at camp. "It’s not awkward," she says. "It’s a very safe place. Like if you start to cry in class, you’ll be like, I don’t really feel comfortable here because they don’t know what I’m talking about or how I feel. But if you cry here, it’s just -- ok, give her some space. We know how it feels."

Tully’s grandmother, her 5-year-old sister, and a family friend she says was like an aunt died in the last year. She says since then it’s been tough to relate to people who haven’t experienced that kind of loss.

"As people start saying stuff and they’re like, “I’m sorry,” and you’re just like -- I get you’re sorry, but that’s not gonna help," Tully explains. "So it’s just a lot easier to cope with people that understand."

She shares that feeling with her group - all teenage girls like her, with green bandanas tied around their wrists or heads, to set them apart from the other age groups. The other girls have similar feelings. Many tell stories about friends who say the wrong things, holidays that feel strange and sad without their loved ones around, fears that they’ll forget or move on.

Then a counselor jumps in. "There’s so many different ways for us to keep that connection with our loved one," she says. A pair of bereavement counselors guide the girls through one such exercise. Eyes closed, the campers imagine everything about a scene - sights, smells, sounds, feelings. Cooking crabs in the backyard with a grandfather, braiding a mother’s hair.

"That’s always something that you don’t have to have a clipboard, you don’t have to have camp, and you don’t have to have anybody to just go there and do that," says one counselor. That’s another goal of Camp Aloha: to give kids ways of coping with difficult and powerful emotions even after they leave.

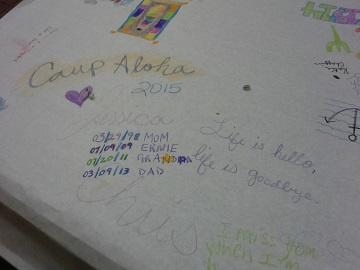

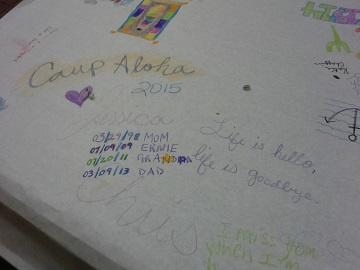

But before they go home, they hold a solemn campfire. Each camper writes a letter to his or her loved one. They introduce themselves and say who they're at camp to honor - the loved one they lost - then place the letter in a large crate. When everyone’s done, the counselors add the crate to the fire. The idea is that regardless of the campers’ beliefs, as their words go up in smoke, the message reaches their loved ones.

As their messages burn, the kids share memories and stories. Sobs ring from the darkness. Barely visible in the firelight, Trina Franken is crying. She’s found Kayla Tully.

"There’s a little girl crying in my arms, and it just reminds me of my little sister," Tully tells the group, crying. "It’s just something that I’ll never be able to do with her."

Kaitlyn Hurst came to Camp Aloha after her dad died when she was 13 - and she’s come back as a counselor every year since. She says the campfire is always her favorite part. "Sometimes that’s what those kids need is somehow to let go," she says. "To let their feelings come out and just be who they are and not keep it bottled up anymore."

The camp’s organizers say it’s important for the kids to express all this emotion - especially here, where they feel safe with other kids who can relate. It’s another step on their way to feeling OK again.

Read more about support services for grieving kids at GPB's Atlanta Considered blog.

A note of disclosure: Camp Aloha is run by Hospice Savannah, which is a GPB underwriter.

Tags: camp aloha, hospice savannah, grief, bereavement camp, atlanta considered