Section Branding

Header Content

Deluxe: Jacqueline Allen Trimble and How to Survive the Apocalypse

Primary Content

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: to celebrate National Poetry Month, Chuck explores the poetic works of black Southern women, specifically those of Dr. Jacqueline Allen Trimble. Dr. Trimble, along with her friends and colleagues Ashley M. Jones and Honoree' Fanonne Jeffers, offer valuable insight into the unique power of poetry to not only inspire, but to educate.

Chuck Reece: In the middle of the 1960s, two different images of the Southern lawman — burned themselves into Americans’ brains.

One of them was fictional, given to us by the CBS television network.

Andy Griffith (as Sheriff Andy Taylor): Howdy, Mister Darlin’! What in the world brings you down out of the mountains?

Chuck Reece: That’s the voice of Andy Griffith, the North Carolina-born actor who played the sheriff of the fictional town of Mayberry.

Ah, little Mayberry, where Sheriff Andy didn’t even even need a gun to keep the peace.

The other icon of Southern law enforcement was not fictional. His name was Theophilus Eugene Connor. He was the public safety commissioner of Birmingham, Ala. You might recognize him by his nickname — “Bull.”

Bull Connor: You can never whip these birds if you don’t keep you and them separate. I found that out in Birmingham. You’ve got to keep the white and the Black separate!

Chuck Reece: Jackie Allen, a young African American girl growing up down in Montgomery, watched Andy Griffith every week with her parents, just like I did.

Jackie Allen — known today as Jacqueline Allen Trimble — grew up to be a poet. She is also the chair of the Department of Literature and Languages at Alabama State University, the historically Black university in Montgomery, where she still lives. This is her reading a portion of her poem, “American Happiness.”

Dr. Jackie Trimble:

The sheriff had no gun,

just an Aunt Bea baking pies

and an Opie full of freckles heading off to fish

or sing or court. Whatever Opies do.

In Mayberry, no doors were barred or locked.

The jail was mostly empty.

The only water hose we ever saw

lay peacefully

curled

on Sheriff Andy’s lawn.

Chuck Reece: The same week when Briscoe Darling came down out of the mountains to get some help from Sheriff Andy, Dr. Trimble’s family watched that other iconic Southern lawman, Bull Connor, on the news. They watched him turn Birmingham’s high-pressure fire hoses on hundreds of young Black people as they marched for their civil rights. They watched Birmingham lawmen beat them with batons. They watched Bull Connor’s attack dogs bite those kids.

This is Dr. Trimble, reading the ending of “American Happiness.”

Dr. Jackie Trimble:

We dined on mashed potatoes and buttered corn

right before our TV sets,

mesmerized,

that in this Southern town,

the sheriff used his hose to water Aunt Bea’s roses.

We were so happy and relieved

we laughed until we could not think

until we fell off our sofas and wing-backs and cane-bottoms;

we laughed until we could not see or hear

until we could forget

that outside our own windows

other sheriffs with loaded guns, snarling dogs, and ready hoses

made quick work of a world on fire.

Chuck Reece: Long ago, I worked in politics — and for a little while, with the ragin’ Cajun, James Carville. One time, he told me there was nothing I needed to learn about life I could not learn by watching The Andy Griffith Show. And you know what? I actually believed him.

Then, a few years ago, I read Jackie Trimble’s book. I saw the stark contrast she drew between Andy Griffith, whom I loved, and Bull Connor, whom I hated. And I saw the even starker contrast between how white Southerners like me looked at the world back then and how Black Southerners like her were forced to look at the world back then.

And suddenly, I saw a truth I had never acknowledged. Dr. Trimble's poem, like God, had taken my blindness and given me sight.

THEME MUSIC UP

Chuck Reece: I’m Chuck Reece, and welcome to Salvation South Deluxe, a series of in-depth pieces that we add to our regular podcast feed hoping to unravel the untold stories of the Southern experience by letting you hear the authentic voices that make this region truly unique.

Today we will talk to Jackie Trimble and to a couple of her friends: Ashley M. Jones, the poet laureate of Alabama, and Honorée Fannone Jeffers, author of the bestselling Oprah’s Book Club pick, The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois.

We will discover the power that lies in the poetic voices of Black Southern women.

And I will tell you about the lesson they taught me.

THEME MUSIC OUT

Chuck Reece: That thing I said earlier? Where I compared the power of a poem to the power of God? I know that might strike you as hyperbolic and I meant it to sound that way, because I’m trying to show the power of just a few words to get inside into your soul and move stuff around. I also said it to tell you specifically how Jacqueline Allen Trimble’s words did that to me. Explaining that requires a little background.

When I was a teenager, I used to leave the music playing in my car whenever I stopped to gas up. More often than not, it was Led Zeppelin at a very high volume. And more than once, an adult told me to turn it down.

Here’s why I tell that story.

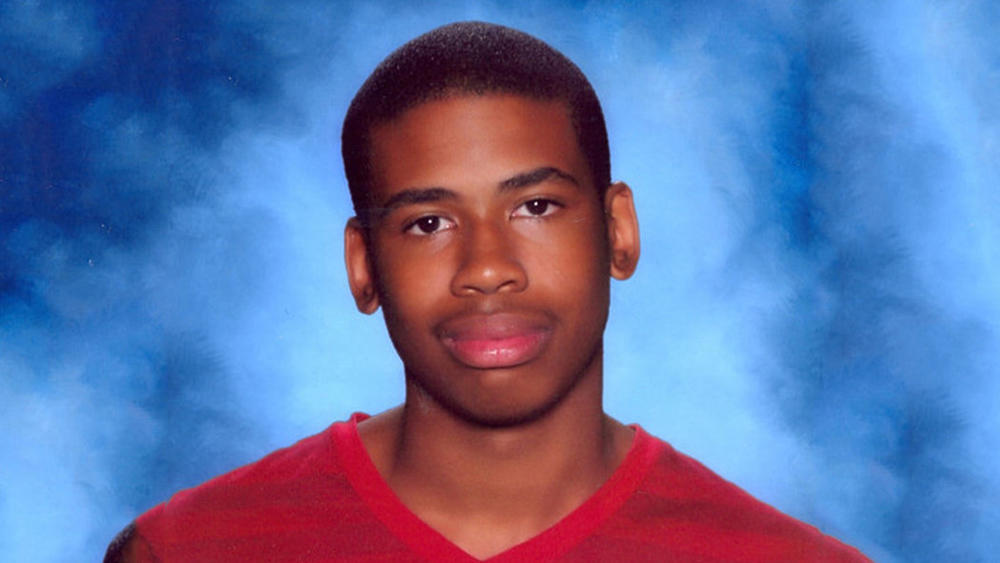

In 2012, a young Black man named Jordan Davis — only 17 years old — was riding in his friend Tommie’s SUV with two other kids, listening to hip-hop at a loud volume, when they pulled into a gas station in Jacksonville, Fla. A minute or two later, a 45-year old white man named Michael David Dunn pulled in alongside them. Dunn declared to his fiancée, who was with him, that he hated either, and I quote, “that thug music” or “that rap crap.” Testimony differed on which actually he said. While his fiancée went inside to buy wine, Dunn pulled a pistol and began firing at Jordan Davis. He hit him three times, one in the leg and two in the chest, which pierced his heart and a lung. Then Dunn crouched in a shooter’s stance behind his car door and kept firing at the other three kids.

Dunn is now doing life without parole for the first-degree murder of Jordan Davis, plus 90 more years for the attempted second-degree murder of the other three.

The news of that shooting made me angry. And confused — because I had been in that same position dozens of times when I was a teenager. But I never worried for a second that someone who didn’t like "that rock and roll crap" would shoot me.

Something became clear to me when Jordan Davis was murdered: that I really knew nothing of what life was like for children of God whose skin was darker than mine. So I started reading. I cannot get inside that skin, but I can read the stories of people who live inside it every day. I picked up the work of Black authors and dug in. Toni Morrison. James Baldwin. Langston Hughes. W.E.B. Du Bois. Natasha Trethewey. But only when I read Jackie Trimble’s first book of poetry, American Happiness, from 2016, did I feel that someone had put certain things I needed to understand right in my face. Where I could see them. Where they could not be avoided.

Her poetry not only gets in the face of our region’s past, but it also confronts the political landscape of the South today. Remember when the Florida Department of Education released its revised African American History curriculum? Soon after, Dr. Trimble wrote a new poem called “A Note to Florida Legislators on the Skills My Ancestors Allegedly Received During Their Period of Enslavement.”

This is Dr. Trimble reading the beginning of that poem.

Dr. Jackie Trimble:

Shall I thank you for teaching us commerce?

Was the auction block a tutorial in fair trade? And anatomy.

Folks stripped to the waist and on down. Perused and pawed.

But you’re not wrong. I owe much gratitude to my ancestors

who learned to snatch dignity from probing eyes,

to hang on to humanity despite laws that made them property.

Chuck Reece: That thing I just said about “in your face”? Now, you get it.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: For me, poetry is a way of making sense of things that don't make sense. And because my field is American literature, And so when you study American literature, you have to, of course, study American history, because they go hand in hand, because the writers are responding to their environment, their context. So for me, everything is related to everything else. And so I am really trying to work it out. I'm really trying to make sense. And I think because I am a teacher — I've taught college students almost 40 years now — I am always trying to think about how to connect the dots, how to make connections among things that seem at times disparate but certainly are related. … I have been put in the role, for decades of explaining things to people, making things plain. And so maybe that's where some of that comes from, that kind of education in American history and the education in American literature, and then looking at the world and trying to make sense of it.

Chuck Reece: In much of Doctor Trimble’s poetry, you will encounter her finely honed skill with irony. It’s like she looks at white folks who don’t understand Black life, raises her eyebrow, and says, "Really? Let me explain it for you."

Dr. Jackie Trimble: I have a very ironic sensibility. I'm fascinated by irony. Absolutely.

Chuck Reece: She comes by that sensibility honestly. Just look at the spot where she grew up in Montgomery.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: I mean, I grew up on West Jeff Davis Avenue and the cross street of the street I grew up on became — it was Cleveland Avenue, but it became Rosa Parks Avenue. So at one time I lived at the crossroads of Jefferson Davis Avenue and Rosa Parks Avenue. And to me that was so emblematic of what it is like to be a Southerner. We are always at these crossroads of things that seem diametrically opposed.

Chuck Reece: Truer words have rarely been spoken.

When you learn about Jackie Trimble’s life story, it’s not hard to understand how she developed this ability to speak her truth so directly when she writes. She was 5 years old when her family moved to Montgomery. But her first years were spent in Tuskegee. It was a small town, fewer than 10,000 people in the mid-1960, but it was the home of Tuskegee University. A historically Black school founded during Reconstruction, in 1881, with Booker T. Washington as its first leader.

Tuskegee was like no other town in Alabama.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: Everywhere, I saw Black business owners. All the doctors were Black. You know, the professors at the university. It was like my whole world was shaped by — The people who were in authority to me were African-American people. In my childhood brain, that was just the way the world was constructed. So it never occurred to me this idea of, you know, inferiority or second-class citizenship. It had never entered my mind.

So even when I came to Montgomery, and I ended up for a time being the only Black child in this school, I had a very clear sense of myself, my value, my self-worth.

Chuck Reece: By the time she arrived at age 5, she had already been educated by a truly exceptional mother.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: She worked in the SCLC. She was engaged in the protest movement. And so she was always telling me things. I was like, "yeah, yeah, mama." You know? "Yeah, yeah, mama." But that gave me a certain kind of an education that a lot of people did not have access to.

My mother was a very well-read woman. And she also the first financial secretary for the Montgomery Improvement Association.

Chuck Reece: Which means that Erna Dungee Allen, Jackie’s mother, worked directly with the Montgomery Improvement Association’s first president, whose name was Martin Luther King Jr.

King and other Black ministers and leaders formed the MIA in 1955 to run the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. It came together in response to the arrest of Rosa Parks, who sparked the civil rights movement by refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery city bus.

By the time Jackie reached middle-school age in the early 1970s, she was reading — and thinking critically — at a level much higher than her years. Here, we’ll let her take us back to Edward T. Davis Elementary School.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: I remember very distinctly being in, like, the fifth or sixth grade. And I remember the teacher, Coach Edwards, one of my favorite teachers, because he was like the coach, you know, and I played sports and he taught us sort of everything. But one of the things he taught us was history.

He was talking about how benevolent slaveholders were and how well they treated the enslaved people because they were valuable and they had to clothe them and do all this stuff. And I raised my hand, and I said, “Well, that's not really true; that is not what the experience of enslavement was like.” And I remember he got very upset with me.

And he just looked at me. He said, “Well, that's what the book says.” That's what the book said. And I was — even though I was really young. I was smart enough to know. "Oh" — and I remember this thought, it's so clear to me! — "he doesn't know. He doesn't know!" I went home and I told my mother, and she was like, "Oh no, no, no, no, no, no, you’re right." You know, that was — that's crazy, he doesn't know any better," blah blah blah blah.

It was like the first time I realized that grownups and particularly teachers who I loved — I loved, you know, school, I loved my teachers — could be ignorant.

It made me way more skeptical about everything I read. And, you know, and I think it sort of — this was the moment that I began my life, not as a writer, but as a scholar. As someone who kind of deconstructed text and said, "No. No, I don't think so."

Chuck Reece: Her poems are very, very good at saying, “No, I don’t think so.” This is Jackie reading the end of her “Note to Florida Legislators.”

Dr. Jackie Trimble:

Hey, maybe you taught us to sing, to give America

its American sound and look and pop? Like the swing in Presley’s hips

or the blues in Gershwin’s rhapsody. Nah. I’m just playing.

What could you know of chariots and still waters

until we told you? And religion? Your evil catechisms

and vengeful god kept us where you wanted us. But we all know

that was a theology fit for nothing. Chile, we had already

met God by the river where He molded dark earth and blew

His breath until we were a living soul. I could see if you claimed cruelty

and greed as your main lesson, the inhumane flowing like a fount,

but resilience? Man, please! We learned to survive you on our own.

Chuck Reece: Salvation South Deluxe will be right back after this break.

MIDROLL BREAK

Chuck Reece: I talked at the beginning of this show about how I believed Jackie Trimble’s poetry had taught me things about the experience of Black people I would not otherwise have understood. And I wondered whether poetry — as opposed to prose or music or visual art — had a special power to do that.

So I consulted the poet laureate of Alabama, Ashley M. Jones, who considers Jackie Trimble a mentor.

Ashley M. Jones: If I were to, you know, walk up to you and say, "Let me teach you A to Z what it's like to be a Black person," that conversation is not going to be enjoyable for either of us, first of all, but it's not going to be as to-the-point as the poem will be. And it also requires you to do some of your own self-study, some of your own, you know, reflection that I can't do for you.

I think we are finally realizing why poetry matters. But it always has mattered in this way. It's just that we've been willfully ignorant. Or maybe we've been afraid of the power that it has, because it does create room for that difficult dialogue. It creates room for empathy. It can tell you that this system, which you think is benefiting your life, is actually controlling you and minimizing your humanity.

Chuck Reece: Okay. So that helped me understand. That poetry — at least poetry of the sort that Trimble writes — can start a difficult dialogue with me. And then challenge me to sit back and absorb it. To understand it. To take it to heart.

But I still wondered if there was something uniquely special about Trimble’s poetry. So I consulted one of her longtime friends, Honorée Fannone Jeffers. Professor Jeffers’ name might be familiar to you. After penning five widely lauded books of poetry, she published her first novel, The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois. After reading it, Oprah Winfrey declared it — and I quote — “a masterful epic,” and made it an official Oprah’s Book Club pick, and that catapulting Jeffers into the literary stratosphere. Her family roots are in Eatonton, Ga., and she has known Trimble for almost three decades, since they were in graduate school together at the University of Alabama.

Honoree Fanonne Jeffers: I call her my Day One. I was 26, and I think Jackie was in her early 30s. She was a young mother. She had two small children. She was in the Ph.D. program, and I was, in the masters of fine arts in creative writing, at the University of Alabama.

It was very lonely, and I was a very impetuous, kind of messy, you know, young girl. And Jackie was real calm.

Some people didn't want me in the program. And people would constantly, you know, bring up things like affirmative action and that kind of stuff. That was shaming and hurtful and all of that. But I think the blessing in it was that I worked five, six times harder than everybody because I was trying to prove myself. But Jackie always said to me, “Girl, you don't need to prove yourself. You're smarter than all these people.” And I was like, “You're just saying that.” She's like, “No, I'm not."

Chuck Reece: And in the years that followed, their friendship remained strong. After finishing her doctorate in 2002, Trimble began a long teaching career — first at Huntingdon College in her hometown of Montgomery. And now, she chairs the Department of Literature and Languages at Alabama State University,

Jeffers also began a long teaching career — today, she holds the Sutton Chair of English at the University of Oklahoma. But she immediately began publishing poetry. Her first collection, The Gospel of Barbecue, came out in 2000.

And over the next two decades. Jeffers kept writing poetry and teaching. And Trimble just taught.

Or so Jeffers thought.

Honoree Fanonne Jeffers: I didn't see her poetry until Jackie was in her 50s. I did not know she wrote poetry. So all this time we're friends. And I had no idea she wrote poetry.

Chuck Reece: Wow.

Honoree Fanonne Jeffers: I had no idea. And then I saw the poetry and it was so — I mean, you've seen my blurb on the back of her first, book of poetry.

Chuck Reece: That blurb reads as follows: “Jacqueline Trimble waited a long time to publish her first book, but she is right on time. I longed for her kind of poetry, these cut-to-the flesh poems, this verse that sings the old time religion of difficult truths with new courage and utter sister-beauty. And I am so grateful for her gift, her grown-woman poetics.”

Honoree Fanonne Jeffers: Wise, insightful and gorgeous imagery. And I was like, "What? What is happening? How did I not know about this?" And she said, “I never told you.” In true Jackie form.

To know Jackie, to see Jackie, you know, in action is to see this classy, gracious woman. To read her poetry is to see what's inside of her. To see what's inside of that extraordinary mind of hers. And to see this sort of raw — yet beautifully crafted in the poems — but this raw anger. And this urgency.

Yes, she's my friend. But I think that there are very few Black women poets — or women poets, period, or poets, period — in America, in contemporary American poetry, that are doing what Jackie is doing.

Chuck Reece: To have a conversation with Trimble is to get a clear demonstration of the class and grace Jeffers talks about. It’s also to get a sense of her teacher’s soul, her willingness to guide others, to help them see the light.

Alabama poet laureate Ashley Jones first met Trimble in 2018, when she launched the first Magic City Poetry Festival in her hometown of Birmingham.

Ashley M. Jones: So our very first year, 2018, we had some funding to do an event that talked about civil rights 50 years forward. We needed somebody local who could also speak to the moment. I had read some of her poetry, and I was like, "let's get this Dr. Trimble person." And she came to read and the rest is history, honestly. I mean, she just blew everybody away.

After you meet somebody once, they just keep popping up in your life, you know? And so me and Jackie have just been popping up in each other's lives and, you know, staying in contact. She's been such a mentor to me.

I want to be like Jackie when I grow up — for real, in every way. You know, as a woman, as a Black woman, as a Southerner, as a scholar, as a poet. Like, she is incredible and so generous, so kind.

As a Black person, it feels like, finally someone is saying this thing that I've been saying forever. Please stop hiding behind what you think is the right thing to do and understand that we’re all suffering. This is a battle for our humanity.

Over the years, I've really come to embrace my Southernness. And I really appreciate what I've what I've gotten from this culture. And what I have gotten is not the culture of hate: it's the knowledge of that culture. But it's also the culture of movement, the culture of seasoning my food well. The culture of — of admiring life at a slow pace, and always loving something fully, which means to call it out on its mistakes, and not just act like they don't exist.

Chuck Reece: Jackie Trimble’s first book of poetry taught me much I needed to know. I loved its delicious sense of irony, its absolute fearlessness about clearly stating the naked truth.

It actually reminded me of the punk rock music I’d loved in my 20s. Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols yowling, “God save the Queen! She ain’t no human being!” and all that.

When I mentioned that notion to Honorée Jeffers, she completely got what I was saying.

Honoree Fanonne Jeffers: It is punk rock! It is like punk rock! Jackie's work is really in your face. And then she'll pull back just enough — when you start getting terrified — and then just quietly say something.

Chuck Reece: But when Trimble’s second collection, How to Survive the Apocalypse, came out in 2022, I found a poem that was hard for me to read. Hard for me to stomach.

It was called “Allies.” It is a pile of statements, one atop the other with no breaks, that come out of the mouths of well-meaning white folks like me, who speak, too often, without understanding.

It begins with this line: “Thank you for letting me know you voted for the Black guy.”

About midway through, you run into these five:

you loved your Black maid

your Black maid loved you

your favorite singer/actor/writer is Black

you never see color

you have two Black friends

And “Allies” ends with this:

your grandfather did not know any better

when he grinned for the camera

beneath the charred body.

The poem was hard for me to read because I thought I WANTED to be an ally. I thought I was SUPPOSED to be an ally. When I told Jackie that, she taught me the greatest lesson of all: that simply being an ally, a supporter, a middle-aged white guy in a Black Lives Matter T-shirt, was not enough.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: So I have a really good friend, a wonderful friend. We've been friends for decades. Decades. She is a white woman who grew up in North Alabama. But we are — I mean, we're real friends, you know, not just kind of “Oh, that's somebody I know.” And she read that poem and she says, “Oh, God, Jackie.” She said, “I don’t…where can I enter this poem?” And her suggestion to me was to put it in couplets. She said, “So maybe they'll give me a little resting place between.” And I said, “No, I'm not going to do that.” I said, “Because here's my issue, here's my thing, here's what I'm really trying to say: I don't like the word ‘ally.’ And I don't like the word ally because an ally is like a person who cheerleads from the sideline. This is a person who says 'I'm not going to get in your way. I'm down for your cause. Do I.' But an ally doesn't have to stand shoulder to shoulder with you.”

Chuck Reece: Her lesson was this: I had to learn and understand how and why white supremacy hurts me, a white guy.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: Because what happens to you is not just something I have sympathy or empathy for. What happens to you matters to me. It affects me. It directly affects my life. And until we realize that, we are never going to get anywhere in this race conversation. You can't just be for my cause. It has to be YOUR cause. And what people in this country have got to realize is that race and racism and white supremacist patriarchy is not just a mechanism that controls Black people and people of color. It is a mechanism that controls white people, too. Because what it has done to generations of white people is it has kept them fighting against their own self-interest.

And I think when people realize that: "You know what? I'm not an ally. This is my war. This is my war for the soul of democracy. This is my war for the republic. This is my war for a better opportunity for my children." Because when the public schools go down, it's not just going to affect people of color. When voting rights get messed with and, and, you know, voter registration — all these things about mail-in ballots — It's not just affecting people of color.

When they build three hundred and some-odd prisons in the state of Alabama, and they're only 144 Walmarts and only about 22 hospitals, that just doesn't affect Black people.

Chuck Reece: Mm-hmm.

Dr. Jackie Trimble: That's what to me that is about. It’s saying you know, please stop being so complacent. Please realize you got to be a soldier, not just an ally, because this is your war, too.

That's more than you ever wanted to know. But there it is.

Chuck Reece: But really, that wasn’t more than I wanted to know. Turns out, it was exactly what I wanted to know.

We’d like to thank Jacqueline Allen Trimble, Honorée Fannone Jeffers, and Ashley M. Jones for their help and cooperation in producing this episode. Having these truly extraordinary Black women speak so truthfully to me has been a privilege I will never forget.

You’ve been listening to Salvation South Deluxe, proudly produced in cooperation with Georgia Public Broadcasting and its network of 20 stations around our state. Every Friday, we add a new three-minute commentary about Southern stuff to our podcast feed, and every month or so, we add longer, dee-luxe stories, such as the one we’ve just told you. I’m Chuck Reece, your host and the editor-in-chief of Salvation South, which you can find 24/7 at SalvationSouth.com.

Our producer is the mighty Jake Cook, who also composed our theme music. GPB’s senior podcast producer is Jeremy Powell, and none of this could have happened without certain amazing people at GPB, including Sandy Malcolm, Ellen Reinhardt and Adam Woodlief.

We’ll be back next month with another full-length episode of the Salvation South podcast.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. Salvation South Deluxe is a series of longer Salvation South episodes which tell deeper stories of the Southern experience through the unique voices that live it. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and wherever you get your podcasts.

In this episode of Salvation South Deluxe: to celebrate National Poetry Month, Chuck explores the poetic works of black women, specifically those of Dr. Jacqueline Allen Trimble. Dr. Trimble, along with her friends and colleagues Ashley M. Jones and Honoree Fanonne Jeffers, offer valuable insight into the unique power of poetry to not only inspire, but to educate.