Section Branding

Header Content

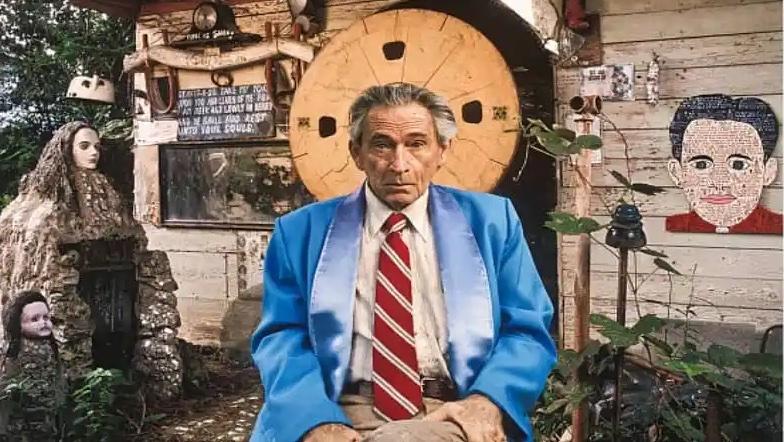

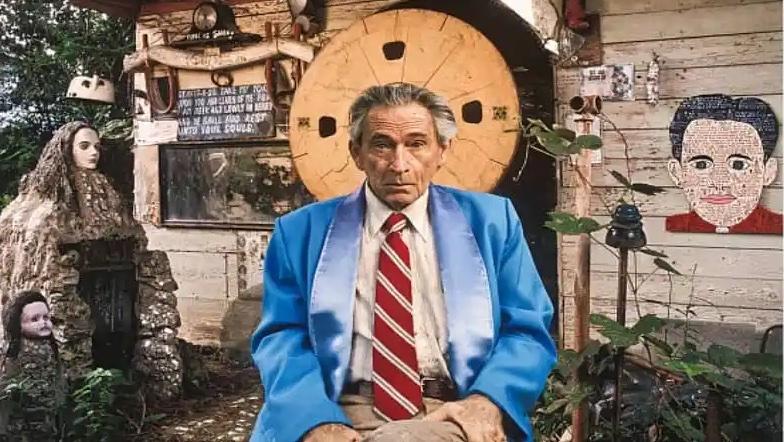

Howard Finster, Man of Visions

Primary Content

One of the most famous painters the state of Georgia ever produced never took an art class. Instead, he was a small-town preacher. He believed God called him to paint what he called “sacred art.” Salvation South editor Chuck Reece remembers a day he spent with Howard Finster forty years ago in this week's commentary.

TRANSCRIPT:

In my house is a piece of Georgia folk art that I treasure. It’s painted on a piece of discarded paneling, cut with a jigsaw to fit the image. It depicts a young boy wearing coveralls and a too-big fedora. He has the wings of an angel. And painted on one leg of his coveralls is the inscription:

Elvis at 3 is a angel to me. By Howard Finster. From God. Man of visions.

Pennville, Georgia, is a little outside Summerville in the northwestern part of our state. That was where the Reverend Howard Finster lived, a character of the sort who could be found only in the rural South. I’ll never try to sell my “Elvis at 3.” I bought it from Howard himself for fifty bucks about forty years ago. I expect it’s worth a good bit more than that now. Another thing I’ll never forget? The times I visited Howard at what he called Paradise Garden.

Paradise Garden is a one-and-a-half-acre wonderland of Howard’s creations. Not just paintings, but pathways and buildings. I can’t describe the place, because Paradise Garden is too otherworldly for words. You should just head to Pennville to see it for yourself. The Paradise Garden Foundation has restored it beautifully.

When I was at the University of Georgia, a band you’ve probably heard of called R.E.M. made the video for its debut single, “Radio Free Europe,” at Paradise Garden. As a result, when the band got famous, Howard’s art did, too.

When I made my first college pilgrimage to Pennville, I got the same story about how Howard started making art that everyone else who visited him got. Here’s the way I remember it. Howard told me and my friends that he used to make wooden toys for kids in the community, and he painted them with tractor enamel. Then he looked at us and he said, “One day I dipped my finger that paint, and a face come in that paint. And that face looked at me and said, ‘Howard, paint sacred art.”

He got that calling straight from God, and boy, did he ever follow it. And his art now hangs in museums all over the world.

He amazed me in my youth. Howard Finster showed me that the hellfire-and-brimstone preachers of my Southern small-town upbringing could influence the great world beyond. It had the power to draw fancy New York curators of art into a place that was so familiar to us, but so foreign to them.

Now, I look back and think that visiting the good Reverend Finster forty years ago might have led me to my own calling. Trying to tell the stories of the astonishing South, in all its weird and wonderful glory.

I hope you’ll come read some of those stories at SalvationSouth.com.

Salvation South editor Chuck Reece comments on Southern culture and values in a weekly segment that airs Fridays at 7:45 a.m. during Morning Edition and 4:44 p.m. during All Things Considered on GPB Radio. You can also find them here at GPB.org/Salvation-South and please download and subscribe on your favorite podcast platform as well.

One of the most famous painters the state of Georgia has ever produced never took an art class. Instead, he was a small-town preacher. He believed God called him to paint what he called “sacred art.” Salvation South editor Chuck Reece remembers a day he spent with Howard Finster forty years ago for this week's commentary.