Section Branding

Header Content

The Drive Toward Change

Primary Content

This weekend, the 125th United States Open Championship returns to one of the oldest golf venues in the United States, Oakmont Country Club in suburban Pittsburgh.

Sixty-two years ago, the 1963 U.S. Open was held in Brookline, Massachusetts, and two local Georgia amateurs were attempting to qualify at East Lake, home of the Atlanta Athletic Club.

A white man and a Black man teamed together.

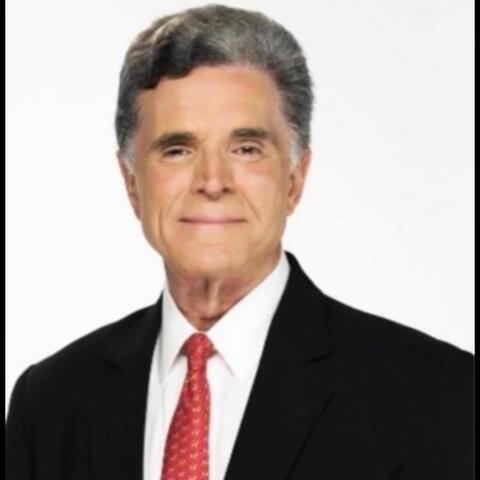

“I received a call from Woodrow Wilson Bryant who was in charge of the (golf) East Lake bag room,” recalled Georgia Sports Hall of Fame inductee, First Tee founder (emeritus) and Georgia Tech legend Charles Harrison. “He said, 'Your qualifying playing partner tomorrow is a colored man.'”

Mr. Harrison responded, “Is he a good player? That’s all that matters.”

Mr. Bryant, an African American, replied, “He is a good player; I watched him.”

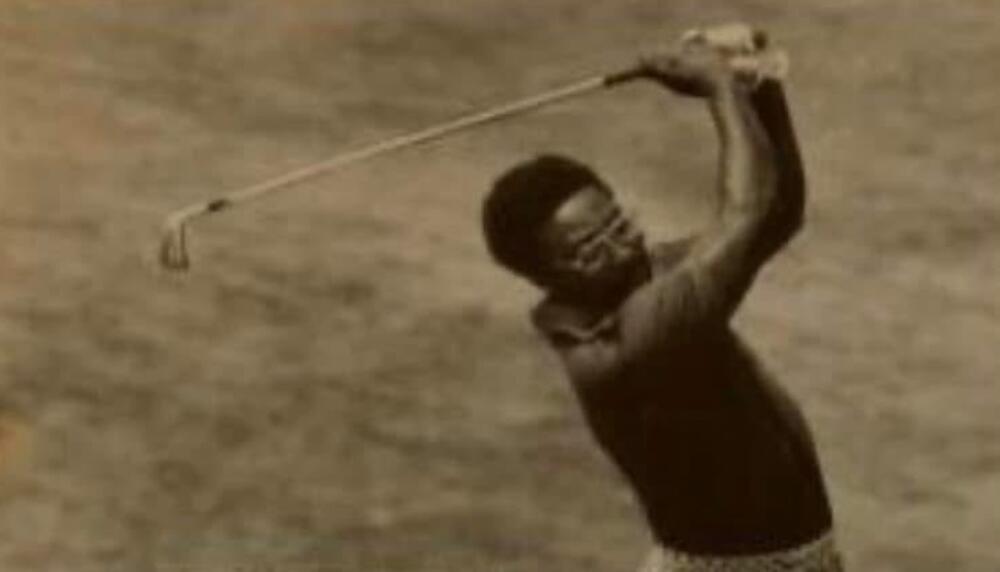

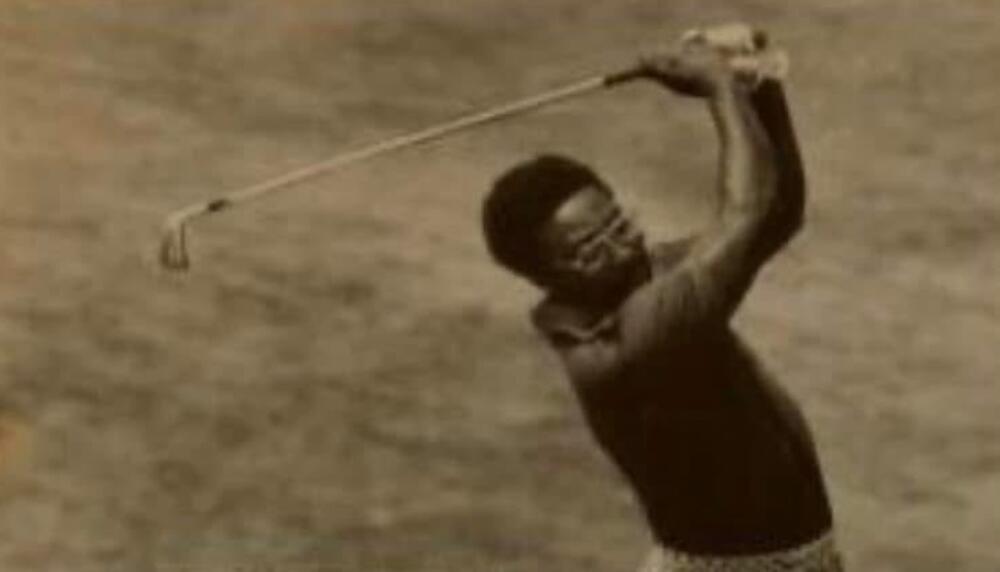

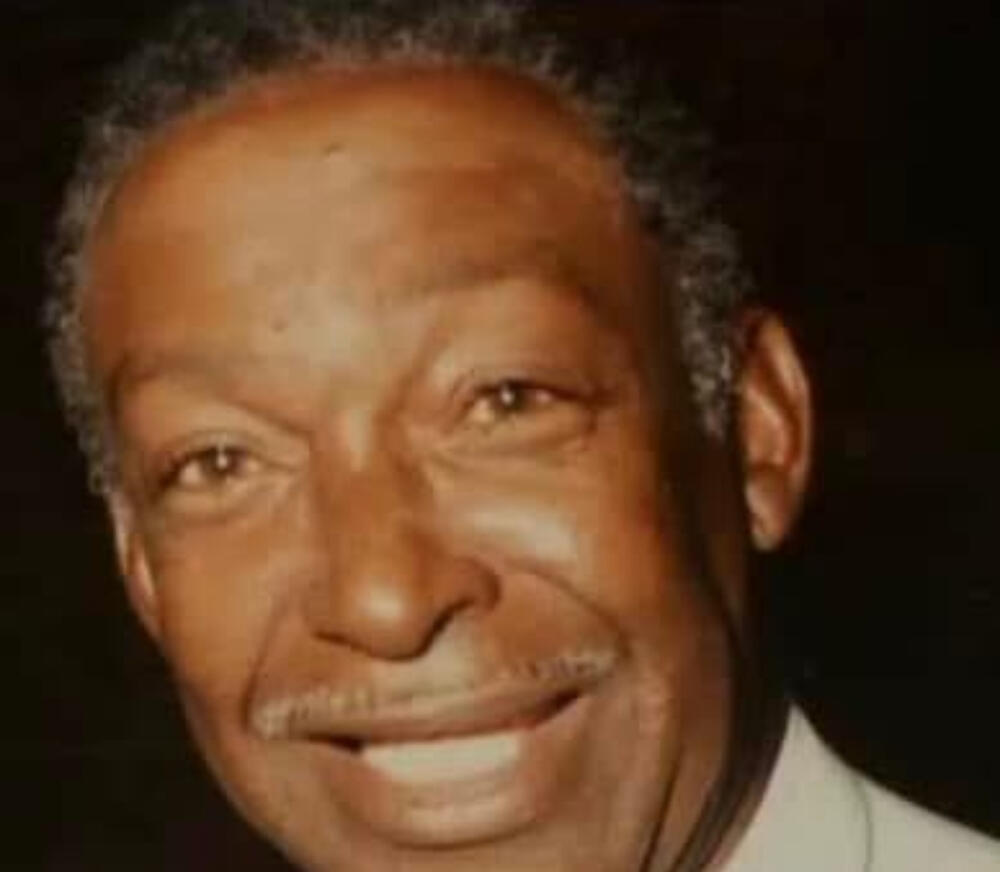

George Johnson, born in Columbus, Ga, learned golf at the age of 15 when he caddied at a nearby segregated country club in South Georgia.

He advanced, playing where he could in Georgia, and by the summer of 1963, had the certification to compete for a U.S. Open spot.

“When George first appeared at East Lake, Woodrow (Wilson Bryant) and Jim Brett, in charge of the caddies, pointed him toward the (caddy) pews. George told them 'I’m here to play,'” recalled the Atlanta legend with crystal clarity.

“He was nervous on the tee box; all eyes were on him," Harrison said. "George played well through 16 then faltered on the final three holes shooting 80. I fired 69.”

Qualifying was 36 holes, 18 in the morning, then lunch, and another 18 in the afternoon.

The Atlanta Athletic Club celebrated the players with a great buffet. Mr. Harrison invited Mr. Johnson to have lunch inside the all-white Atlanta club.

1963 was a momentous year in the civil rights movement. Segregation remained in the full force.

An Atlanta golf lunch was the issue in June.

A woman member congratulated Mr. Harrison on his low round, “under your circumstances.”

The two men returned to the golf course, Mr. Harrison shot 72 and qualified for the US Open.

Mr. Johnson did not, but would make it two years later in 1965 and, in 1964, would turn PGA pro.

Following the golf and lunch with a Black man, Charlie Harrison was asked to write a letter to the AAC president explaining his actions of the day.

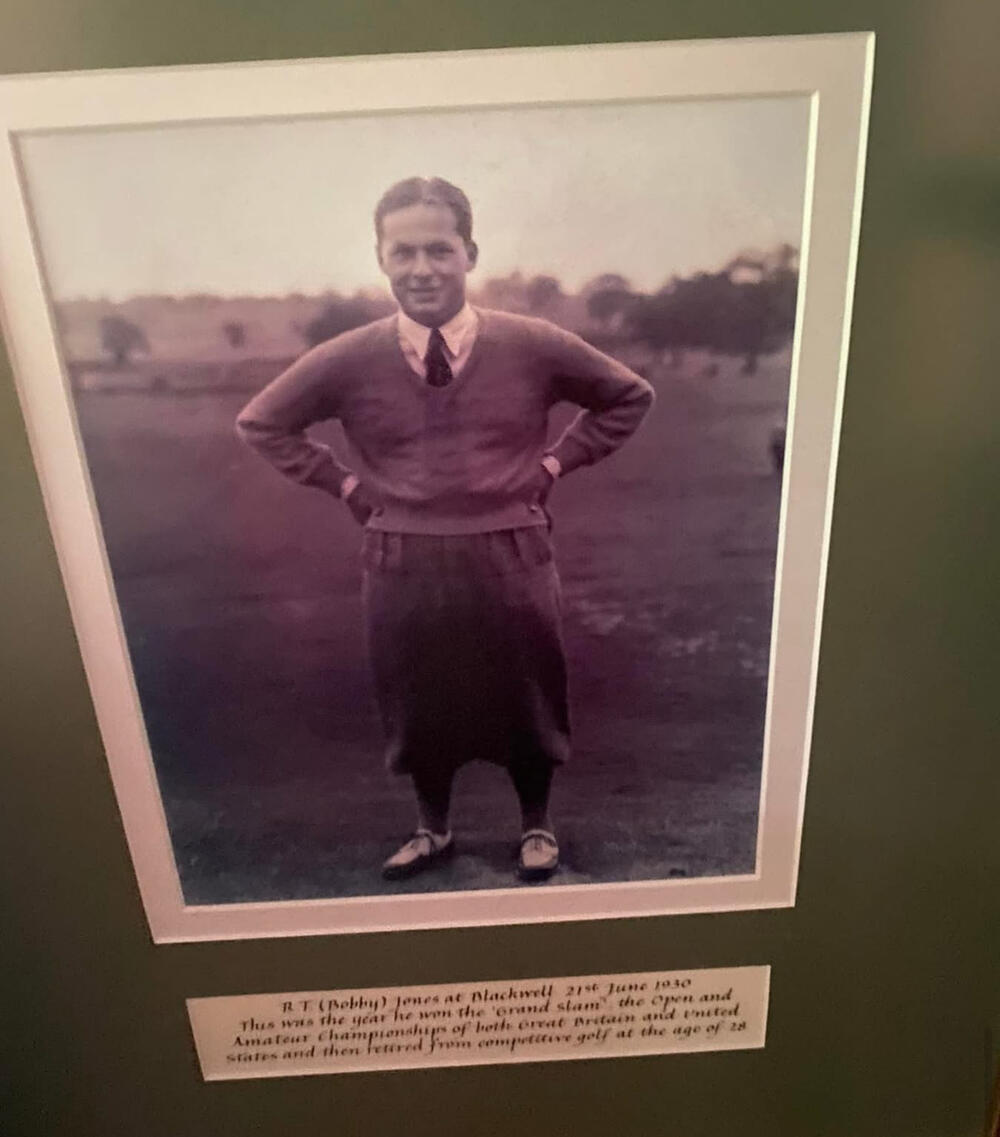

“I went to see Bob Jones (immortal American amateur golfer, attorney, and co-founder Augusta National) in his office, he backed me — I’m on record, anyone who qualifies at Augusta National will play no matter the race or creed.”

“Trouble was still brewing at East Lake,” said Mr. Harrison.

It appeared, the Atlanta Athletic Club was going to pull his membership over the lunch invitation.

“Tommy Barnes (Atlanta golf legend) told me, 'I have bad news Charles, some of your friends want you kicked out for taking Johnson to lunch.'”

Mr. Harrison had a simple defense.

“He (Johnson) was a player and they (Atlanta Athletic Club) had lunch for players. I invited him to have lunch.”

Charles Harrison kept his membership.

Meanwhile, George Johnson led a full golf life, played with Jack Nicklaus and Tom Kite.

In 1971, he won the Azalea Open and became the fourth African-American to ever win a PGA tournament. George spent 10 years on the PGA Tour and three on the Senior Tour and was a Lifetime Member of the PGA. He became the head professional at a Louisville club in 1997.

Famed Atlanta metro golf teacher, author and Golf Magazine Top 100 Mike Perpich told me he played with Mr. Johnson on the mini tour, saying “he was a wonderful guy and player."

George Johnson died in 2014 and is buried in East Point.

There are so many unknown stories not of the dimension and scope of Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Bill Russell or Texas Western basketball. Here is a small story ushering in change to 1963 Atlanta.