Section Branding

Header Content

Bringing Primary Sources Into The Classroom

Primary Content

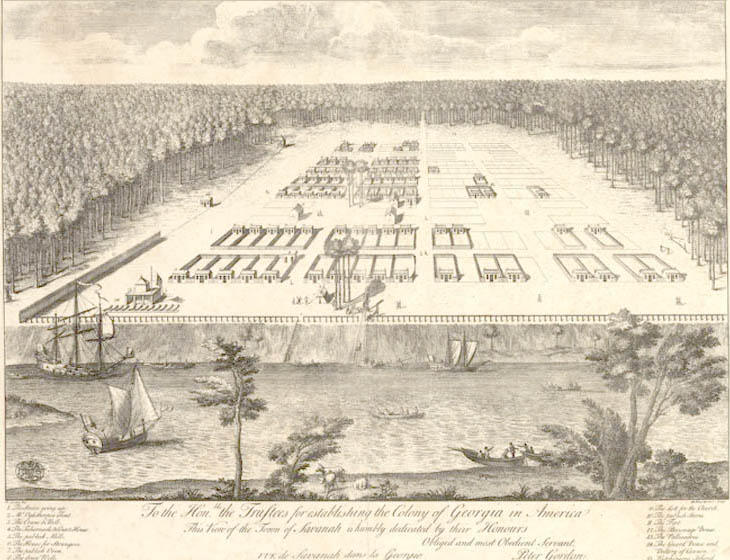

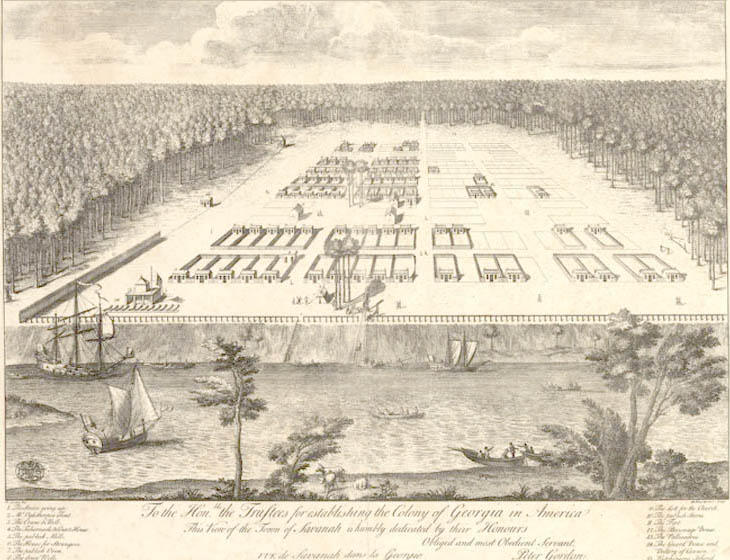

Quick. What year was the Battle of Hastings? How many justices are on the United States Supreme Court? Who is the author of the Wealth of Nations? Far from trivia night, these questions should sound familiar to any student or teacher who has experienced the traditional social studies classroom. And reinventing this approach of recalling names and dates is an idea as old as some of the treaties and treatises that we learned about so many years ago. So it should be no surprise that something this old is new again. The Georgia Department of Education reminds instructors that the “goal of social studies is not to have students memorize laundry lists of facts.” Instead, the intention is “to help them understand the world around them so they can analyze issues, solve problems, think critically, and become informed citizens.” Enter a renewed focus on primary sources, defined by the Library of Congress as the “raw materials of history — original documents and objects which were created at the time under study.”

Differing from secondary or tertiary sources created by those interpreting or researching the past, these sources are the living and breathing evidence of the humanities. The National Archives has analysis sheets and lessons for every period in American history. PBS’s History Detectives offers nearly fifty lessons on primary sources and nearly twenty research techniques. Our own Georgia Studies digital library is filled with primary material for all of Georgia history along with a “Historian’s Toolkit” in chapter three designed to support student inquiry of primary documents. We offer transcriptions of famous documents along with other primary material like posters, ads, or campaign buttons. GPB’s World War II Oral History Project, as well as our blog covering the March on Washington anniversary, have more topical resources for teachers to explore. We also publish a newsletter for Georgia Studies that describes primary materials throughout Georgia history. Here are some ideas for using primary sources in the classroom:

- Mock Trial. Collect some of the most useful primary sources from many accounts and perspectives of an incident or event and divide students into prosecution and defense. A great example is the mock trial of Henry Wirz.

- Spectrum of Significance. Cut up different paragraphs of related documents and ask students to rate their section as more important or less important in terms of answering a critical thinking question of your choice. Have a debate with students over why they rated their sections the way they did.

- Photo Editor. Offer students famous photographs from important events. Tell them that they are to take on the role of a photojournalist or editor and come up with a caption for the picture. Remind students that the caption should interest readers but also explain what is happening and why is it significant. The Print and Photograph Catalog at the Library of Congress hosts a large collection as well as the National Archives.

- Go Sources! It’s Your Birthday!. Have students bring in several sources from the day and month of their birth surrounding a famous event or person in history. Students can send written tweets about something they learned.

- Jigsaw Map Puzzle. Print overhead maps of battles, regions, etc. cut them up. Students might rotate between multiple centers for specific periods then all come together to discuss what all the maps had in common.

For more activities, the Library of Congress blog has two pages of ideas and our partner, Discovery Education, has a blog post with more suggestions. Oh, and those answers from the beginning are 1066, nine, and Adam Smith. But you remembered that from school, right? Of course you did.

Quick. What year was the Battle of Hastings? How many justices are on the United States Supreme Court? Who is author of the Wealth of Nations?