Section Branding

Header Content

Forgotten Women Part 10: Mother Mathilda Beasley

Primary Content

The second round of the Forgotten Women series concludes with Mother Mathilda Beasley. Beasley is known as the first African American nun in Georgia. She dedicated her life caring for orphans and bravely educating slaves when it was illegal to do so.

But many details about her life remain a mystery.

Some members of the Savannah community working to keep Beasley’s memory alive.

Chatham County Commissioner James Holmes is a member of the Catholic Church Saint Benedict the Moor. He spoke to Beasley's mystery.

"She’s untold. And when I say untold. They hear Mother Beasley, they hear Mother Beasley. But they don’t really know, who is Mother Beasley."

Holmes played a major role in getting the former East Broad St. Park renamed after Beasley 1982.

But he wants to do more to increase awareness, including erecting a monument in the park.

"If I could take off a year I would dedicate a year to researching her work," Holmes said.

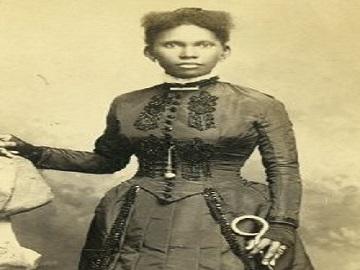

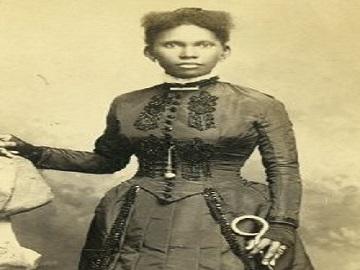

A picture believed to be Beasley shows a tall slender woman dressed in all black.

Very little is known about Beasley’s early life.

We do know she was born into slavery in the 1830’s as Mathilda Taylor, in New Orleans. She was most likely had an African American mother and Native American father.

Beasley somehow obtained her freedom and arrived in Savannah around 1850. It was before the Civil War and educating slaves was a criminal offense. Punishable by quote “a fine and a whipping.”

But researchers like Katy Pereira, the Director of Archives for the Diocese of Savannah, suspect she ran a secret school despite the risks.

"Either out of her house or in connection with some land somewhere else maybe…If she was doing that it was a risky way to care for the communities of color of the kids," she informed.

It was in Beasley’s nature to sacrifice to for the needs of others. She married a wealthy free man named Abraham Beasley. When he died she gave all of her money to the church and started an orphanage. The St. Francis Home for Colored Orphans.

"We talk about carism in the church and the call of the Holy Spirit and what God is calling the community to do," said Pereira. "She felt called to serve the communities of color, particularly the children."

Commissioner James Holmes agreed.

"I don’t think people realize when they say these are our future. But how much are you doing to develop that child?

Here goes a lady that had no birth child but her wealth her care her loving, she saw it fit to put it into somebody else."

Beasley traveled to York England to receive instruction in her faith. When she returned she established The Third Order of St. Francis,Georgia’s first community of black nuns.

But it wasn’t easy maintain the order or the orphanage. The nuns eventually disbanded and funds for the orphanage began to run dry. It’s possible that while all of the Beasley’s inheritance went to church, not everything was used for funding the orphanage.

Katy Pereira said this is when Beasley began constantly writing to members of the Catholic church for support.

"Man she did not give up. I mean you want to talk about tenacity and perseverance and it was in a time when women may not have had the same respect as they do now and she was a woman of color so that was another layer to how people responded to her...I’ve always very much admired how much she just sort of took the reigns and was like okay this is what I want to do and this is what I feel like I’m called to do and God’s calling me so how are we going to do this?"

In her last years she even worked as a seamstress to continue to provide funds for the church. Perhaps because of that persistence more people than ever may finally know about her accomplishments.

Mother Mathilda Beasley’s home given to her in her final days by Sacred Heart Church has been preserved and is being made into a museum.

Becki Harkness is with Coastal Heritage Society. The organization was engaged by the county to do structural research on the house to determine what it may have looked like during Mother Beasley’s occupancy.

It was rough start. A lack of photos gave architects little information to go on.

But, now, they’re almost ready to beginning installing panels detailing Beasley’s life.

Harkness said, "The house is a way of letting people experience her life. Giving it a space to tell her life story."

Mother Mathilda Beasley died in 1903 in her home chapel. She’s said to have been kneeling in prayer, with burial clothes folder beside her.

Beasley's legacy lives on in the work of the Mother Mathilda Beasley Society.

Tags: mother mathilda beasley, gabrielle ware, forgotten women, GPB Savannah, GPB