Section Branding

Header Content

On this unassuming trail near LA, bird watchers see something spectacular

Primary Content

It's early morning in the San Gabriel Mountains and we're standing in an unremarkable dirt parking lot. The hills around us are dotted with chaparral vegetation, and Los Angeles sprawls just south of here. To me, this looks like any other trailhead in the greater LA area.

But we're here, at Bear Divide, to witness an incredibly rare spectacle of nature: this is one of the only places in the western United States where you can see bird migration during daylight hours.

When our NPR team arrives, Kelsey Reckling is already here, scanning the horizon for birds. She is a PhD student at UCLA who studies bird migration.

Bear Divide is unique because it's like a passageway through the wall of the San Gabriels. Birds are funneled through, Reckling says, and fly low enough for researchers to identify, catch and study the species as they pass. On a really good day, Reckling says, you can see up to 20,000 birds zooming by as they travel north for the summer.

Bear Divide was only discovered as a migration hotspot in 2016. But since then, bird nerds like Reckling have flocked here to catch a glimpse of just one moment along the epic migration journey. Some of the birds we'll see today are traveling thousands of miles — flying from as far as South America all the way up to Alaska.

As the sun peeks over the horizon, the show begins. I hear a chorus of chirping break the silence of the valley.

"Oh here we go," Reckling says as she spots a group of warblers coming. "We've got a black-throated gray warbler, a hermit warbler."

She punches the numbers and species into a tablet, adding to a detailed database of bird sightings she and other researchers will use to study not just birds, but also bigger trends in the natural world.

"You know the canary in the coal mine saying? If we understand what's happening to birds, we might be able to understand broader changes in the environment, in climate and things like that," says Ian Davies of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Davies flew across the country just for this. He stands near Reckling armed with a pair of binoculars, calling out bird species for her to enter into the database.

Spotting these birds can be difficult, with my untrained eyes. The birds are small and quick. But all it takes is a fleeting speck in their peripheral vision for Reckling and Davies to ID a bird. Sometimes they identify birds by song alone.

A Townsend's warbler flies by, followed by a hermit warbler and a lark sparrow. I miss all of them, because as soon as Reckling and Davies spot them, they're gone.

"That's the thing about this place and many other migration spots," Davies says. "You get about one second, and in that one second you can see beautiful things. But by the time you're asking, it's already gone."

While Reckling and Davies watch the skies, another group of researchers just a few hundred feet away is getting a much closer look at the birds.

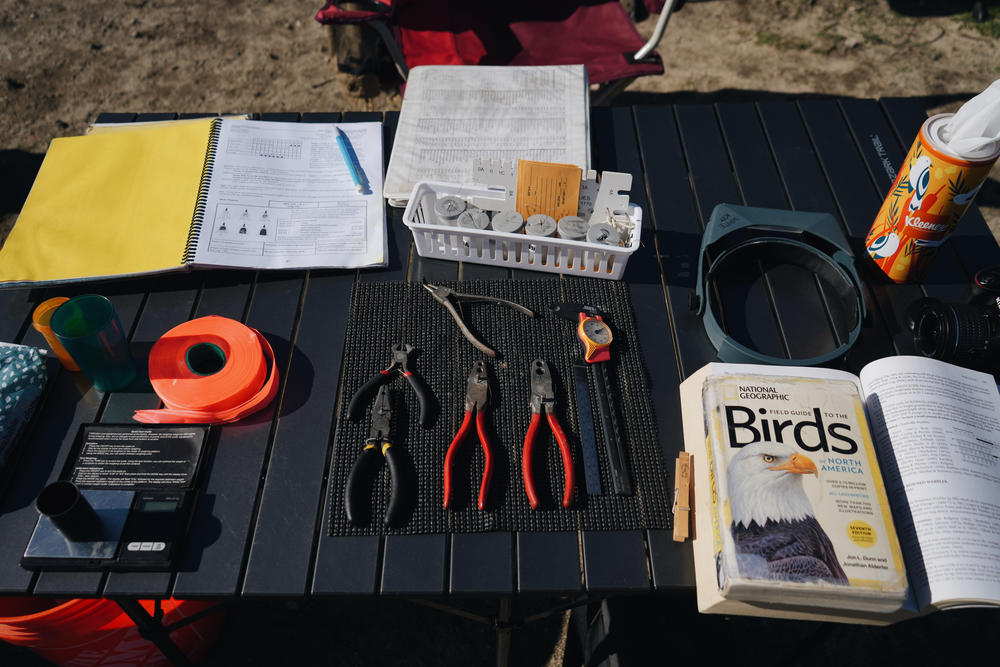

Lauren Hill is a grad student at Cal State LA, and she co-leads the banding station at Bear Divide, where researchers catch, tag and measure birds.

As they fly through, some of them get caught in barely visible mesh nets stretched across the brush.

Hill starts an up-close examination of one of them.

"This is a house wren," she says, as she holds the bird in what's known as a bander's grip, its head secured between her middle and index fingers.

She clamps a tiny bracelet with a nine-digit identification number to the bird's ankle – "Almost like their social security number," she says. Then she measures the wing length and weight. She also checks the condition of its feathers, and takes a look at its reproductive organs to determine if it's preparing to breed.

After a few minutes, she lets the bird go and he's back on his journey.

Hill says the scientific goal of the banding station is to build a long-term database to monitor the health of bird populations flying through Bear Divide. But beyond the science mission, the research here is uniquely accessible to the public.

"I feel like there's a lot of gatekeeping in science," Hill says. "We try to make this place welcoming to everybody – anybody who wants to see a bird, anybody who wants to ask a question. We engage with everyone and encourage people to come up."

While we visited the banding station, a small crowd of hikers, families and bird enthusiasts gathered around another researcher holding an orange-crowned warbler.

Tania Romero, a grad student at Cal State LA, co-leads the banding station with Hill.

Romero says that when she was growing up in south LA, she wished she had this kind of access to scientists, because she had no idea that science was a career option for city kids like herself.

"I didn't really figure this out until my last year in undergrad, that I could even study birds for a living," Romero says. "Because I think for the longest time, I felt that I was not a part of this – I couldn't be a part of this."

By the end of the morning, bird sightings are starting to slow down, so we head back to Reckling to get a recap and final tally of the day.

"Lots of different warblers, some buntings, a few orioles. We have counted over 850 birds this morning," she says. "I'm happy with today."

Bottom Content