Section Branding

Header Content

Indian Affairs Promised To Reform Tribal Jails. We Found Death, Neglect And Disrepair

Primary Content

At least 19 people have died since 2016 in tribal detention centers overseen by Indian Affairs, our investigation found. Several died after correctional officers failed to provide proper medical care.

Transcript

NOEL KING, HOST:

A person is sent to jail for a minor infraction, like having an open container in public or petty theft. And then days or even hours later, that person is dead. This is happening on Native American reservations.

NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau have been investigating what's going on as part of a member station partnership. With me now, Cheryl W. Thompson, who's an NPR investigative correspondent and a senior editor working with member stations, and Nate Hegyi who's a reporter for the Mountain West News Bureau. Hello to you both. Thanks for being here.

NATE HEGYI, BYLINE: Thanks for having us.

KING: Cheryl, let me start with you by asking, what were the questions that you and Nate were investigating, and what did you find?

CHERYL W THOMPSON, BYLINE: We found a pattern of mismanagement and neglect in tribal jails that led to the deaths of at least 19 men and women since 2016. Those jails are overseen by the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs. Corrections officers at several detention centers often violated policy by not checking on inmates regularly or ensuring that they received medical care. We also found that 1 in 5 guards have not completed the required basic training, which includes CPR, first aid and suicide prevention.

KING: What is a tribal jail, and who ends up in them?

HEGYI: These are often small jails in rural towns on reservations. There are 77 of them around the country, and the inmates who died included a grocery store butcher, day laborer, transients. But we've been noticing the same pattern over and over - people were intoxicated, preventable deaths. One of the victims was Carlos Yazzie. Yazzie showed up at a jail on the Navajo Nation in 2017. He needed medical attention. His blood alcohol content was nearly six times the legal limit. His brother Chris says Yazzie had struggled with alcoholism. It stemmed from a traumatic childhood.

CHRIS YAZZIE: A lot of times he acknowledged, you know, hey, I'm a drunk, yeah, you know, I'm addicted to alcohol.

HEGYI: In January 2017, Yazzie drank a dangerous amount of booze. Still, instead of taking him to a hospital, guards put him into a cramped isolation cell just after 1 a.m. Federal policy requires guards to check on inmates every 30 minutes. But a medical examiner's report found that they left Yazzie unmonitored for six hours. He died in his cell from acute alcohol poisoning, an autopsy found. It's a condition easily treatable by medical professionals.

Chris used to work in the jail. He believes his brother's life could have been saved if guards followed policy.

YAZZIE: The corrections officers are basically - you know, are holding these lives in their hands with their decisions, you know.

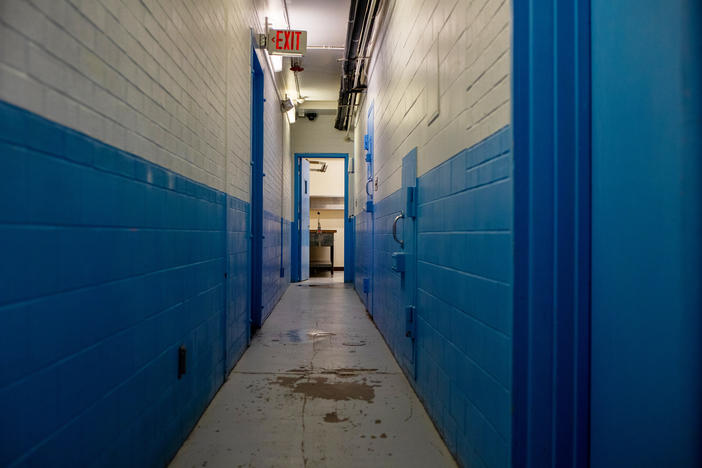

HEGYI: The jail where Yazzie died was more than 60 years old. It was dilapidated. And it's not the only one. Ophelia Begay gave me a tour of the jail at Window Rock, Ariz., on the Navajo Nation. She's the supervisor.

OPHELIA BEGAY: You know, the plumbing is terrible.

HEGYI: The plumbing's broken, drinking water is often brown, the lights buzz, and the roof leaks.

BEGAY: During the rain, my staff has to set buckets in these areas or try to continue to mop because we don't want to slip.

HEGYI: Like many reservation jails, Window Rock is short staffed. The guards pulled triple duty like working as cooks and...

HANSEN ATTAKAI: We're also custodians, so we keep this place clean.

HEGYI: That's Correctional Officer Hansen Attakai. He says the job is stressful. Unlike other federal detention centers, there are no doctors or nurses on site here. Guards are often responsible for making potentially life-or-death decisions about an inmate's health.

ATTAKAI: All I will say is that we're not doctors (laughter). We don't know all the knowledge that they have. So...

HEGYI: At least a third of inmates in tribal jails are arrested on drug- or alcohol-related charges. They are potentially at risk of dying from withdrawal-related seizures or alcohol poisoning. Ian Paul is a forensic pathologist at New Mexico's Office of the Medical Investigator. He says these jails need trained health care providers.

IAN PAUL: If you are going to place acutely intoxicated or heavily intoxicated people into a holding facility, there should be at least one person there with a medical background that can monitor them clinically.

HEGYI: There wasn't a doctor or nurse on site in May 2020 when Willy Pepion ended up at the jail on the Blackfeet reservation in Montana. Pepion was at a house when witnesses told authorities that a fight broke out and someone hit him in the head with a shovel. When police arrived, they arrested him. He was taken to a hospital where doctors cleared him to spend the day in jail. But they missed a serious injury. The shovel had cracked his skull. No one from the hospital would comment. When police took him to the jail, Pepion had dried blood on his face and in his mouth.

Frederick Noon Jr. says he was in jail with Pepion that day. He says the 22-year-old pleaded for help.

FREDERICK NOON JR: He asked that jailer, can you - I need help, I need help.

HEGYI: Noon says he tried to get the guard's attention for Pepion.

NOON: And I was like, hey, this guy needs help. He's pretty sick.

HEGYI: Federal policy says guards cannot deny an inmate's request for health care services. But sheriff's records show they never brought Pepion back to the hospital. Noon says for the next few hours, Pepion was in pain.

NOON: He wouldn't let his head touch his pillow. It was like he was protecting his head. He looked like a little baby, you know, falling asleep. And he was bobbing his head up and down, moaning and groaning.

HEGYI: Pepion died 10 hours after first entering the jail. Federal policy requires guards to check on inmates every 30 minutes for signs of life. But at the Blackfeet jail, sheriff's records say they didn't. They broke the rules that day. Pepion's body wasn't discovered until nearly three hours after he died. His mom, Wilma Fleury, says she called the jail repeatedly to find out when her son was going to get out. I met her on a bitterly cold February day at her home on the Blackfeet reservation. It had been nine months since her son died. We sat down at her kitchen table, and she said she thought her son was in there for being drunk. The guards kept telling her he'd be released once he was sober. But then, that night, a sheriff's deputy showed up at her door.

WILMA FLEURY: He goes, what's Willy to you? And I thought right away that maybe something happened to him and they're taking him to the hospital or something. I go, he's my son. Why? And he goes, I'm sorry to tell you, but he passed away. And I go (crying) - I said, I been calling all day to see if - when he was going to get out. That's my boy. That's my youngest kid.

HEGYI: Pepion died on Mother's Day. His mom has taken down all of his pictures. They're tucked away in a closet. Seeing them is too painful.

FLEURY: My one friend told me - she goes, some days will make you feel like you're going crazy. So when I start feeling like that, I usually go outside or I take a long walk, be by myself. But then I get really angry.

HEGYI: Angry because she believes her son didn't have to die.

KING: Nate, why does this keep happening?

HEGYI: You know, it does keep happening. Willie Pepion was the third person to die at the Blackfeet jail since 2016 for the same reasons - no doctors or nurses on site, poor training, breaking rules.

THOMPSON: And this has been happening for almost two decades. In 2004, the inspector general for the Interior Department called the BIA jails a national disgrace. And after months of us asking questions about the death, the training and staffing at the jails, an official told us they plan to bring in an outside agency to examine the problems plaguing them. We'll see if that makes a difference.

KING: Hmm. NPR investigative reporter Cheryl W. Thompson and Nate Hegyi of the Mountain West News Bureau. And I should note before we say goodbye that this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center. Thanks to you both for your reporting. We really appreciate it.

HEGYI: Thank you.

THOMPSON: Thank you for having me. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

Bottom Content