Caption

Georgia's 97% turnover rate for entry-level corrections staff is significantly higher than neighboring Florida's 64%, where state lawmakers also approved a similar 10% salary hike for new officers this year.

Credit: Pixabay

|Updated: April 27, 2021 10:10 AM

Georgia's 97% turnover rate for entry-level corrections staff is significantly higher than neighboring Florida's 64%, where state lawmakers also approved a similar 10% salary hike for new officers this year.

Georgia’s criminal justice officials are banking on better pay to stem the staggering near-complete turnover rate for new juvenile correctional officers, who often leave discouraged by the highly demanding jobs that call for keeping order inside detention centers.

Georgia’s 97% turnover rate for entry-level corrections staff is significantly higher than neighboring Florida, which reached 64% a year after state lawmakers there approved a 10% salary hike for detention officers. Georgia and Florida’s retention challenges have become common in states across the nation for correctional departments.

Juvenile Justice Department Commissioner Tyrone Oliver said he’s optimistic additional money will entice more people into a job that can be physically and mentally taxing at times.

It can be tough working 12-hour shifts and getting disconnected from families for long periods of the day while dealing with the stress of the responsibility of protecting children, teens, young adults, and other staff from sometimes violent interactions.

This April, Georgia’s correctional officers’ starting pay grew from $27,936 to $30,730, while experienced officers also got a similar 10% boost.

The juvenile department is also offering incentives for military veterans looking to get into the field, including up to a 10% salary hike. Meanwhile, entry-level salary is about $34,000 for working in Georgia’s higher-security facilities in Augusta and Eastman.

Oliver said he believes the new salaries are a much-needed jumpstart in keeping more officers down the line, noting about two-thirds of employees cited pay as their top concern in an anonymous employee survey conducted last year.

Other selling points are the employee benefits and more salary increases after six months and a year on the job.

“Most of our facilities are in rural Georgia, so coming in and making about $31,000, potentially $40,000 a year starting off is huge,” Oliver said.

But sometimes, people sign up only to quickly realize a career in law enforcement doesn’t suit them. The cost to train a new officer comes out to about $4,000, so it can quickly add up when you’re hiring 200 to 300 people within a given year.

“I often tell people you can pay somebody $1,000 an hour, and they will still leave because it’s not what they want to do and you can respect that in that regard,” Oliver said. “Because it is different, you’ve got to have a passion for it. You have to want to help kids and want to make a difference in these young people’s lives.”

The turnover is high in juvenile and adult systems as people often opt for more lucrative careers with less tension, according to a report from the RAND Corp. and the University of Denver on behalf of the National Institute of Justice.

There’s also the so-called millennial effect felt across the U.S. workforce, with the generation that reached adulthood early this century three times more likely to switch occupations than their counterparts.

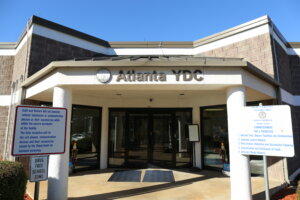

The Atlanta Youth Detention Center is one of 26 secure facilities across the state operated by the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice. The agency’s director says he’s optimistic a new pay rise will reduce the state’s nearly 100% corrections officer turnover.

The report also noted the importance of better compensation as a driving force in retaining correctional officers, but also recommends more flexible work hours, better training and other changes.

“In many states, corrections compensation is simply not competitive with that for occupations in other industries,” the report said. “Finally, the field is challenged by the reality that the public does not consider corrections to be a high-status occupation.”

State Sen. Harold Jones, an Augusta attorney and former prosecutor, said spending more money on staffing should be helpful, but the work conditions would also improve with more staffing. The department used $2.5 million it saved in not filling vacant positions last year to provide a salary boost to 840 officers.

Last month, the juvenile justice department held a virtual hiring fair for new detention staff. The department currently has a little more than 1,200 security employees and has a $322 million budget for the upcoming year.

Jones said he’s hopeful that better pay will lead to officers better equipped to handle potentially dangerous situations because they’ve spent enough time to learn about the challenging environment. Constant staff churn makes that goal elusive.

“We have to realize that you can’t do these kinds of things just by numbers,” he said. “It becomes a situation where you have to learn how to properly manage, whether it’s juveniles or adults. If you have somebody that starts to understand how to do that and in six months, they’re gone, that’s a problem.”

In recent years, Georgia’s juvenile justice system had problems with young people attacking staff and dozens of instances where the department fired correctional officers for excessive use of force.

The department also faced criticism for pressing charges against the juvenile offenders accused of assaulting officers at a higher rate than the staff accused of hurting the youths in custody.

Since becoming the director in July 2019, Oliver has said a primary goal was changing the management style so that the focus is first on the young people in the system and their families.

In the 12 months prior, the retention rate for new officers hit 130%. As Oliver came on board, he pledged to put an end to a bureaucracy that sometimes kept the department’s director out of the loop about physical misconduct allegations against detention staff.

“We’ve changed our culture here at DJJ,” Oliver said. “I think that was one of the main missions that I wanted to do when I got here a little over a year and a half ago. We’re doing that to ensure our staff can be better prepared and better (able) mentally and physically to take care of our youth.”

Georgia began the shift from a tough-on-crime approach to its law and order system to emphasize rehabilitation during the tenure of Gov. Nathan Deal, who counts as his signature accomplishment policies that resulted from his Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform.

Now, there’s more emphasis on turning young people’s lives around when they enter the court system, providing treatment services, counseling, and educational opportunities with an aim to keep young offenders out of detention centers.

Within five years of the commission’s policies taking effect, the number of juveniles in secure facilities dropped 36%.

Omotayo Alli, executive director of the Georgia Public Defender Council, said she is glad more money is going to staff retention and youth development campuses.

To rebuild the criminal justice system, it remains essential to provide enough resources to help children, teens and young adults transcend their current circumstances in order to reach their potential.

“We go beyond just having officers to keep the children safe,” said Alli, who previously served as the chief administrative officer for the Fulton County Juvenile Court. “Our number one goal is we want to keep them safe, but we also want to hope that we get people who want to work in that environment because it’s rewarding.

“We want to effectively represent them in court, but also to get them back on track so that they can grow into happy and healthy adults,” Alli said. “And we’re going to need good detention officers who understand what it means to take the children and get them to the next level.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.