Section Branding

Header Content

Ga. Tech Professor Has Special Reason for Cheering Comet-Chasing Probe

Primary Content

The European Space Agency's Rosetta mission has traveled more than 300 million miles through space to make its historic landing on the 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet. But for A. Nepomuk Otte, that trip also involved a little time travel.

That's because it was 12 years ago when Otte, an assistant professor at Georgia Tech's School of Physics, was asked to help work on the COSIMA mass spectrometer that the Rosetta orbiter will use to study the dust particles coming from the comet.

"I remember back then, when I first got in touch with the company to help with the assembly of the electronics," Otte said, "and they told me they had this crazy idea to land this thing on a comet, which is basically a dirty snowball. I wished them luck.

"That they actually managed to do this is really great, an extraordinary achievement."

Otte was a Heidelberg University undergraduate physics student at the time and he was interested in helping the German company von Hoerner & Sulger build a spectrometer that would be sturdy enough to withstand a 10-year mission through space.

"The purpose of the Rosetta mission and the (Philae) probe is to find out the composition of comets, which are undisturbed chunks of the original stuff of the solar system," Otte said. "They can tell us how the solar system came about, how the planets were formed and also whether traces of life are within them."

The Rosetta orbiter had been gathering that data since August, when it arrived near 67P and began to circle the comet. But Wednesday brought the successful landing of the Philae probe on 67P.

Even with some technical glitches, Otte is impressed that "trying to land something so fragile like this lander on this comet" actually worked considering the calculations that had to be done for objects traveling more than 80,000 mph.

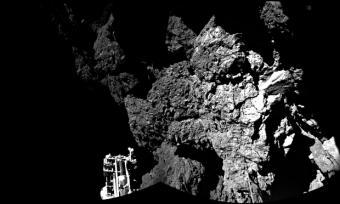

"The most difficult task, which I think is really amazing, is that the gravity of the comet is so faint," he said, referring to the news that the lander actually bounced twice before coming to rest in the shadow of a "cliff" on the 3-mile-wide comet.

As if a tension-filled descent on Wednesday wasn't enough for the ESA project scientists back on earth, more challenges could lie ahead.

Two harpoons that were supposed to anchor Philae to the comet did not fire and screws on each leg were apparently unable to find purchase in the rock, so 67P's weak gravity may keep the ESA from using a bigger drill to study materials deep within the comet. Also, attempts to reposition the lander away from shadows that threaten solar-powered batteries could send it flying back into space.

Otte believes that even if the ESA can't find a way to anchor Philae to 67P so it can stay on the comet as it continues towards the sun, the mission has still been a success.

"I think we (are) certainly learning a lot about the technologies that are necessary to bring people to other planets, like Mars," he said. "The technologies in building these spacecraft and making them rugged so they they can survive a mission that lasts years, that's an important piece of data that will help these missions."

Tags: a. nepomuk otte, COSIMA, European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, 67P, probe lands on comet, the probe that landed on the comet, ga tech professor and comet

Bottom Content