Section Branding

Header Content

What’s Old Is New Again: Newsworthiness In The Digital Age

Primary Content

My first year in the classroom, only a few students owned smartphones, and the iPhone was just two years old. YouTube was in its nascency, and my students, then seniors, had been in middle school the first time a video was posted to the platform. After opening up to the public, Facebook had recently become a household name. That was 2009, and although nine years seems not long ago, the world is appreciably different now.

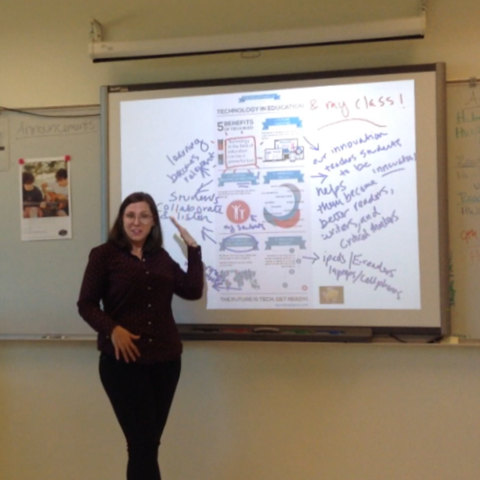

At school, the proliferation of internet technology in the past decade has fundamentally changed the way I plan, collaborate, and execute lessons. Most importantly, it has changed the way my students access and process information. Students have a vast amount of information at their fingertips, but they have a tendency to view all informational text on similar footing: nonfiction is all writing that is true, and they think information exists in a vacuum. To be discerning readers and writers, they will need to develop a more nuanced understanding of news and digital media.

While the verisimilitude of internet information has received much attention in the classroom, it is increasingly important to teach students to examine the rhetorical situation of the information that they encounter. With more and more students clicking headlines via social media feeds or search engines rather than by navigating to a news outlet’s homepage, they read individual articles in relative isolation rather than as part of an editorial spread, overlooking vital details about where, when, and why the article was published in the first place. A 2016 study from the Pew Research Center about news consumption habits found that “when asked if they [study participants] remembered the source of an article they arrived at from a link, about 4-in-10 (38%) remembered every time.” Rather than just looking for bias within individual articles, students should analyze why there is bias in a news media outlet as a whole.

With this in mind, I began my journalism course differently this year. I asked students to reflect on what makes something news. “What does ‘news’ mean?” is a question so seemingly rudimentary that it might feel condescending to ask young adults; however, pushing beyond the simple definition of “it’s news if it’s new” forces students to think about the shades of difference between the scope of coverage and content found on different news media outlets.

Inspired by a lesson from PBS NewsHour’s Student Reporting Labs, I extended our conversation to ask students what makes something newsworthy. The question of worthiness fostered discussion of what news media outlets choose to give coverage and recognition to; in other words, the conversation was about bias and how audience drives content. If Scientific American did not run a story on the gubernatorial election in Georgia, we are not likely view that as the outlet sweeping information under the rug; of course, if the Atlanta Journal-Constitution failed to cover the same story it should rightfully raise red flags.

For students, sometimes a desire to trust a well-known source that supports their viewpoint outweighs their skepticism, and they neglect the process of putting information in context. By being explicit about what news is and why certain topics warrant coverage for certain audiences, we can better equip students for the barrage of information that they will encounter in their lives. Whether students are writing a research paper or reading a post on social media, everything they read contains bias, and the most judicious readers not only evaluate whether information is truthful, but determine where and why bias exists.

Secondary Content

Bottom Content